Imminent war. Almost a year has passed since this phrase said by the US president baffled the world community. However, today, as well as before the full-scale war, there is a strong feeling that the world has been under an illusion of its future stability. In many ways, this situation is a consequence not only of the atrophy of the self-preservation instinct, put to sleep by the “welfare state”, or the faith in “a triumph of democracy” but also of the well-established relativity of understanding of a number of extremely important things. Different countries have entirely different value scales for peace and human life.

Ideology and propaganda are much deeper phenomena than “nationalist bias” or “right-wing populism.” In social sciences, the formal analysis does not provide an obvious understanding of how the leaders’ discourse affects the archetypal societal states. Globalization does not guarantee reduction of the likelihood of wars and conflicts, no matter how obvious that may seem from a formal and analytical point of view.

It is hardly needed to convince the Ukrainian audience that such mistakes are costly. At the level of practical international politics, incorrect assumptions are converted into inadequate assessments and forecasts. Those in turn result in strategic games won by players who are simply more active and aggressive. At the same time, developed countries, being democracies and therefore sensitive to public opinion, easily fall into the trap of narratives that could become convenient covers for chaste pacifism to hidden cunning mercantilism.

In the case of Muscovy disrupting the world order by waging a long war against Ukraine, we see that certain analytical schemes potentially generating the risk of radical underestimation of threats still prevail in the societies of our allies. The transformation of a nuclear state with hypertrophied raw material rent into a fascist dictatorship reflects such underestimation. Global integration continues to be seen as a cure for geopolitical instability. Such underestimations occur even now, more than nine months into the full-scale war. Therefore, it is necessary to look more thoroughly into such analytical schemes.

Globalization and a safer world?

For several decades the idea that globalization brings more stability and democracy has been considered a dominant (if not defining) epistemological axis. The more countries are involved in global trade and finance, the more they lose when faced with discontinued capital flows, falling exports and imports, blocked trade routes, destroyed assets engaged in international exchange, limited access to innovations, etc. That means that in the case of a global conflict, the loss of a unit of international activity leads to the loss of a much larger part of GDP and public welfare compared to an autarky case.

The same applies to democratization. Countries that trade among themselves become more informationally open. This positively affects the diffusion of ideas and the convergence of political regimes. As global trade increases welfare, sooner or later there will be a public demand for political institutions designed to guarantee property rights, which becomes a pressure factor towards democratization. The global competition calls for innovations whose development and spread might run counter to social stereotypes which autocratic regimes use to maintain their power.

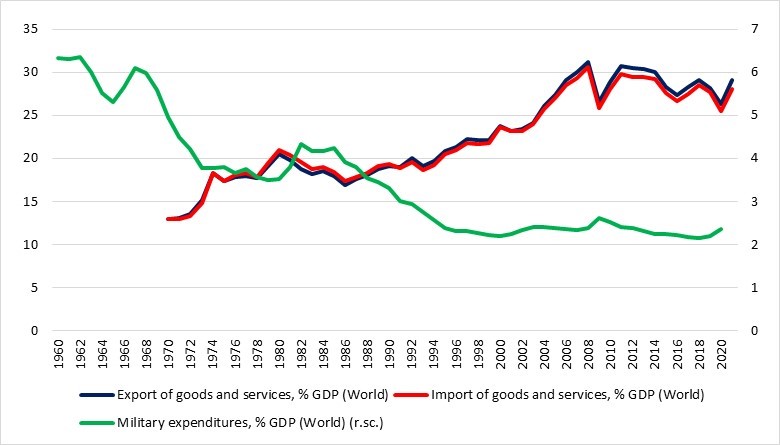

Such lines of reasoning are not ungrounded. After all, trade globalization and military spending data suggest there was some empirical basis for an optimistic view of the future. This is despite the World War I experience, before the start of which globalization was significant, while trade, financial openness and the gold standard made key countries more interdependent than they are now, even despite large military spending. After World War II the situation changed. Globalization started to gradually revive, while military expenses declined. Figure 1 shows that the trajectories of the ratios of global trade and military spending to GDP diverge in the long run.

Figure 1. Trade globalization and military spending in the world

Source: World Bank Development Indicators data

We may get the impression that conclusions about the positive externalities of globalization for geopolitical stability are justified. Moreover, justified enough to make optimism about positive changes in autocracies or hybrid political regimes seem obvious. However, their ability to adapt to new realities has formed an apparent underestimation of potential threats. For instance, in 2017, Rand Corporation experts published a report [1] concluding that the world was likely to become safer within the next few decades. They also highlighted the conflict drivers in the world. Among them is the “degree of economic interdependence” measured by global trade development indicators. Unsurprisingly, the so-called interdependence was promoted as a political argument favoring cooperation with dubious regimes in building North and South Streams, Russia-Germany gas pipelines. The same applies to trade with governments violating human rights. Access to financial infrastructure and asset markets was seen as an extension of the interdependence game supporting stability. It is not at all surprising that at some point autocracies began to blackmail democracies with access to domestic markets or supplies of raw materials.

The evil joke of the common values illusion

Can we dismiss rational analysis? Definitely not. Should we accept the fact of bounded rationality? Why not? Is it appropriate to deny behavioral biases? No. But these concepts are more likely to reflect a specific Western benchmark of rationality. It has limited application where society is distorted by propaganda, where propaganda is primarily aimed at activating the archetypes of “making up for ages-old insults,” “getting up from the knees,” and “old-time grandeur.” Such archetypes then temper new radical dimensions of imperial narcissism by programmed inertia. That makes it highly shaky to apply the analysis of losses and benefits in the Western sense to deeds, actions, or the political course of the countries infected with the virus of undisguised fascism.

In the case of Muscovy, the international underestimation of the risk arising from it not being at the same level of civilization, a commensurate level of perception, and understanding of human values, is particularly threatening. In a society where human life is worth little, the benchmark of loss acceptance falls outside the bounds of a rational approach to analyzing losses and benefits. During the first years of the war in Vietnam in the mid-1960s, the US used General Westmoreland’s strategy, implying that with a certain level of inflicted losses, their replacement would become more and more problematic, which would eventually result in the dying out of the armed resistance. However, was the point of the irreplaceability of losses correctly estimated? The result is well-known. But many international actors in the current war make a similar mistake. A society gripped by the hate virus tolerates losses. An autocratic regime having significant resources from trade in raw materials can transfer losses onto society for a very long time – much longer than any rational conception of the Westmoreland’s point of irreplaceability would suggest. In other words, significant resources, a totalitarian machine, centuries of cultivated sacrifice, and Muscovite loss tolerance reinforce each other on a scale beyond Western perception.

This spawns the following problem: the correlation of the implicit level of losses with the activation of the internal political competition mechanism aimed at de-escalation. A similar assumption is that the seizure of the assets of a number of Putin’s oligarchs will facilitate the emergence of a stable coalition among elites seeking regime change. However, in a society where xenophobia has become the driving force behind mobilizing “sacred forces,” competition for de-escalation policy is a priori impossible. The same goes for oligarchs. In a society where oligarchs are not the product of a species’ struggle to monopolize political and economic power but are appointed for their services to the regime, a coalition headed by a peace-loving Brutus is hardly possible. In other words, betting on imaginary forces with a low casualty threshold and low tolerance for violence is a priori a mistake. Political competition in such a society is possible only to escalate or to radicalize threats as a way of projecting power. Not only would the alternatives be incompatible with the regime’s self-righteous arrogance, but they would not be relegated to the margin as a “degenerate art.” They would be no more than a game of cultural assets for the sake of veiled posing in front of the mirror of Horde-like reflexes acquired in the process of historical experience: the intra-tribal power of the Ulus leader rests on his external victories.

However, such a problem is only intermediate, as it leads to another typical mistake in the behavior of international actors. It is well-known that Genghis Khan ordered his military leaders to move as far westward as possible. What is Muscovy’s ultimate goal? Considering that the mechanism of internal political competition for de-escalation does not work (or, rather, it simply does not exist), there is no deterrence to further expansion either. Competition for greater aggression in the public attention domain leads to a situation where each subsequent act is based not on a specific military (or military and political) goal but on feeding itself. Political self-preservation starts to become increasingly dependent on how strong one’s position is in the competition to increase the level of aggression. And a lack of political competition aimed at de-escalation will make the pursuit of new victories an existential through-the-mirror journey. For this reason no one negotiated with Hitler. Because a society with activated archetypes of aggression and hatred has no rational limit where to stop, where losses become unbearable, or where humanity toward its victims must prevail over the fetishes of victories. This perception error of international actors regarding the ultimate goal of Muscovy’s aggression makes them highly vulnerable: on the one hand, to the fact that entirely different civilizational scales determine their own threshold of losses, and on the other hand, by replacing rational assessment of the situation with self-convincing that there are some quantitative limits that will satisfy the Minotaur after he reaches them.

The paradox of globalization?

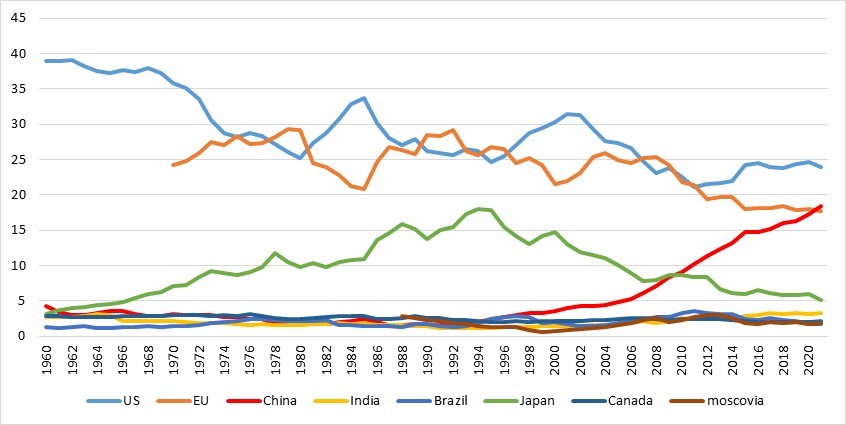

Is globalization indeed nothing more than a cycle of self-destruction? As shown above, perceptions of globalization as bringing geopolitical stability and democratization have turned out to be exaggerated. But is it an exaggeration to suggest that there is a self-destructive gene in globalization itself? The answer to this question is not easy. Globalization creates opportunities, and opportunities can be distributed unevenly, as are raw materials. Military power does not always correlate with the level of well-being. In the process of global integration, some countries have benefited a lot from international exchange and strengthened their positions. In over 30 years of the global expansion of trade and finance, the world has become less concentrated in economic power. Figure 2 indicates that the weakening of developed countries’ dominance benefited China. Should the long-term trend persist, developed countries might lose their leadership positions in the distribution of economic potential.

Figure 2. The share of selected countries in the global GDP, %

Source: World Bank Development Indicators data

International political economy has established that a relatively even distribution of economic potential leads not to greater stability but to greater instability [2]. It is certainly not a reason to believe that hegemonic concepts of global stability are presumably correct (although in the study by Rand Corporation mentioned above, undermining the global primacy of the United States is recognized as a factor directly increasing the likelihood of conflicts). However, accepting the inverse relationship between the trend to multipolarity and the incentives to maintain peace makes it obvious that the fragility of a world without wars is more reminiscent of a cartel collusion of the world’s leading oligopolist players than of a natural choice. And someone quitting this “collusion” threatens the entire world order.

In fact, “quitting the collusion” is the very force triggering the geopolitical tension that turns into war. And here, the different scales of losses and benefits and the ability to look at a partner not through his own lens play a big role. The temptation to make the first step can be driven by entirely irrational factors. Yet it obviously feeds on an utterly rational calculation of a predator, who is more inclined to intimidate a victim and get an additional bonus from it losing its ability to resist [3]. Thus, when global integration creates a situation where it is impossible to avoid losses for everyone, it begins to work not so much as a safeguard but as bait [4]. From a formal economic point of view, this looks like a first-mover advantage for someone with a lower loss tolerance and with expectations that the loss threshold of “competitors” is higher. Such an advantage can take the form of open armed aggression or a threat to inflict losses on the opposite party should it impose restrictions on the unilateral actions of the confrontation’s initiator.

What determines the difference in losses? The ability to blame losses onto others due to the specifics of the trade structure, access to technology, concentrated ownership of a specific class of assets, participation in capital flows, etc. The ability to transfer losses onto a competitor fuels the appetite for unilateral actions. The ability to transfer losses onto one’s own population due to ideology, propaganda, political regime, or cultural codes is as (or even more) important. The problem of the difference in loss scales is most clearly at work in the latter, which puts democracies in a much weaker position than autocracies.

Can globalization be protected from an imminent war?

The answer to this question will depend on the extent to which today’s political elites can accept the fact that a more fragmented global economy can sometimes be more sustainable and that the inconvenience of fragmentation is the price for geopolitical stability. The comfortable gap between economic and military security can no longer be considered a social institution of global integration. In other words, coalitions of countries united by common values, as well as international organizations, should develop an ambitious reform project designed to introduce large-scale and long-term structural measures that will restrain countries/regimes that generate confrontations. This applies to the ownership of reserve assets, FATF requirements, access to payment infrastructure, changes in the international trade regime, etc. At the same time, veto rights are no longer compatible with worldwide stability. The veto right paralyzes the UN, and in the case of the EU and NATO it is obvious that it is enough to corrupt one country with cheap gas, oil or nuclear fuel to destabilize the entire strategic line. In other words, the need for a change is more urgent for developed democracies. They should come out of their welfare hibernation and accept the fact that rational arguments regarding self-destruction safeguards do not work the same way everywhere.

[1] Conflict Trends and Conflict Drivers. An Empirical Assessment of Historical Conflict Patterns and Future Conflict Projections. (2017). Rand Corporation. Santa Monica. California. 289 p.

[2] Obviously, this problem is debatable. In particular, economic potential should correlate with military potential and with geopolitical power in a broader sense. Also, there is a question of how to interpret the power distribution. As a sign of a certain concentration level (in the spirit of the market structure analysis) or as a certain deviation from the status quo power distribution. Loss and benefit analysis from one-sided aggressive actions also falls into the discussion domain; and in the power distribution analysis it has one meaning, while in the deviation from the status quo of power distribution – somewhat different. See Powell R. (1996). Stability and Distribution of Power. World Politics 48. January. The issues of fragility of the world stability to more even power distribution are also considered, e.g. in Wagner R.H. (1994). Peace, War, and the Balance of Power. American Political Science Review 88. September.; Mansfield E. (1992). The Concentration of Capabilities and the Onset of War. Journal of Conflict Resolution 36. March

[3] After the annexation of Sudetenland Hitler looked at the Czech defense line and was wondering that if Czechia would not agree to the Munich coercion, the military operation would not go according to the plan.

[4] The difference between the reaction of the world to the USSR invasion of Afghanistan and Moskovia invasion of Syria is an example that the fear of losses of the less aggressive side widens the operational domain of the more aggressive side.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations