The Ukrainian labor market has suffered a severe blow due to the russian aggression. At the beginning of russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s labor market virtually froze. In March, over 53% of those employed before the war lost work because companies were forced to stop their operations entirely or partly due to property loss, disrupted supply chains, or employee losses. The situation has gradually improved, but unemployment still exceeds 30%. This article looks at how the state has tried to support the labor market and the new regulations adopted in wartime.

Employment: better than expected

The economic downturn caused by the war (an impossibility for businesses to operate in occupied territories or areas near war zones; damaged business assets; disrupted logistics, including port closures) has led to a sharp rise in unemployment.

According to the NBU, unemployment reached 35% in July, exceeding the figure at the end of 2021 (9.8%) by nearly four to one (in the third quarter, the NBU estimated unemployment at 34%). It is due to full or partial closures of business entities and losing or damaging production facilities. In the October inflation report, the regulator foretold a reduction in unemployment to 22.3% at the end of 2023 and 16.5% at the end of 2024. Even though reducing unemployment is quite viable, this indicator is unlikely to reach its pre-war level in the coming years.

In its October outlook, the ILO predicted that employment in 2022 would be 15.5% (2.4 million jobs) below the 2021 level. This forecast is better than the ILO’s April 2022 estimate of 4.8 million job losses.

Due to russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, the State Statistics Service currently does not publish unemployment numbers. This data (probably incomplete since not all data can be collected) will be posted after ending or lifting martial law (Law of Ukraine No. 2115-IX). Therefore, only indirect unemployment estimates are available from surveys of the population, companies, job vacancies, and job seekers on job search sites. There is a significant increase in the number of candidates for every vacancy on all such websites. Therefore, the reduction in jobs was even greater despite many of the workforce moving abroad.

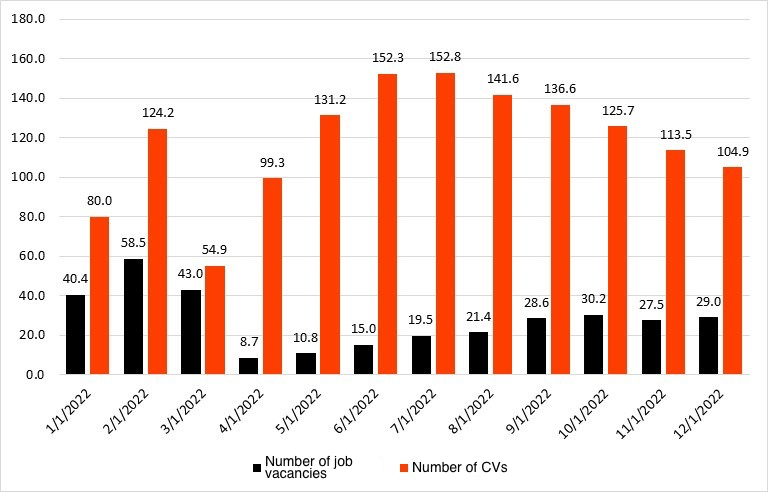

For instance, as of February 1, 2022, over 95,000 vacancies were posted on Work.ua. In March, their number decreased by almost 14,000; in April, the site listed only 14,012 actual vacancies, which is 15% of the “pre-war” level (Figure 1). The number of vacancies gradually increased from May but never reached the pre-war level by December.

Figure 1. Number of vacancies and CVs on the work.ua website for 2022, thousands

Source: job search site Work.ua; per year; new per week

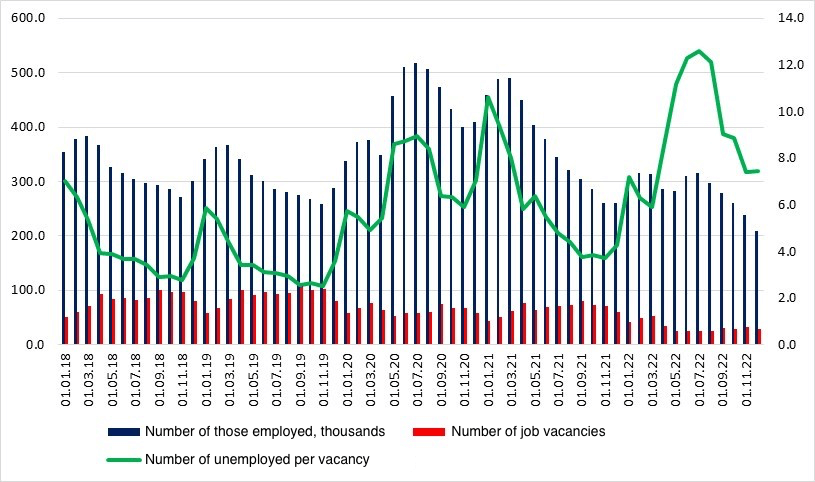

State Employment Service data show a similar trend (Figure 2). In April 2022, registered unemployment and vacancy numbers began to fall. In May and August, the SES reported an unprecedented 12 candidates per vacancy. By the end of 2022, this indicator was back to the level at the end of 2021 (7 candidates per vacancy). The decrease in registered unemployment numbers might be caused by the caps on (up to 90 days) and size of (up to the minimum wage) unemployment benefits during martial law.

Figure 2. Registered unemployment and job vacancies at the beginning of the month

Source: State Employment Service

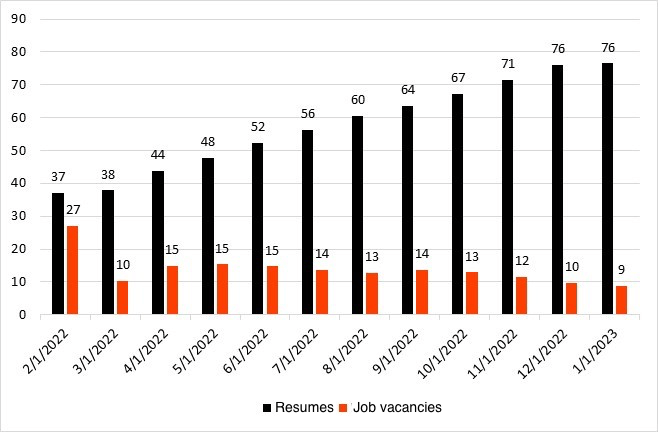

The full-scale invasion also affected the IT sector, causing a significant increase in resumes and a decrease in the number of job vacancies since February 21.

Figure 3. Number of IT specialists’ resumes and job vacancies, thousands

Source: job search site Djinni.com

In late March 2022, over half of Ukrainians employed before February 24 lost work after the start of the war; 45% continued to work (half of them as before and the rest remotely or part-time); and only 2% found new jobs. Instead of layoffs, some employers cut their employees’ wages, reducing the salary offered to new employees. According to Work.ua, in May 2022, the proposed pay decreased slightly compared to January, returning to its previous level in early January 2023. However, with 26% inflation, actual salaries have reduced significantly.

The recovery of jobs has been uneven across regions and industries, with vacancies recovering the fastest in the Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk regions. Service sector specialists (retail, logistics, and restaurants) are in the greatest demand.

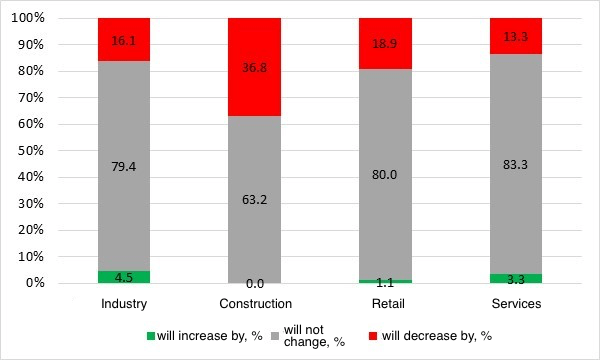

In 2023, businesses expect the economy to recover, but most companies do not plan on hiring more workers, and significant levels of unemployment do not encourage raising wages (Figure 4). 73% of business owners are talking about raising salaries, while 26% intend to keep them as they are.

Figure 4. Companies’ employment expectations

Source: NBU’s survey of companies, December 2022

Retraining employees, integrating veterans and internally displaced persons, and returning refugees into the labor market will pose significant challenges during Ukraine’s reconstruction.

Today, employment centers offer various retraining programs, enabling people to learn a new specialty demanded by the market. The State Employment Service and the Ministry of Economy launched the National Staffing Reserve program. In addition, the government plans to expand the public works program (even though not many people are currently involved in it).

Relocation of businesses to the west and abroad

In order to preserve businesses and equipment, the state launched a relocation program in March to be used by companies in the risk zone due to the ongoing hostilities. The program offered companies assistance to relocate to the west of Ukraine (select a production facilities site, transport and accommodate personnel, and find new employees). The digital interaction platform to assist with relocation was designed to streamline the process. One could fill out a relocation application on Prozorro.Sales website.

Over 700 enterprises used the business relocation service in 2022 (a tiny share of about 240,000 active Ukrainian businesses), thanks to which it was possible to save over 35,000 jobs. The largest number of companies (661) were relocated in the year’s first half, with the relocation pace decreasing significantly after July. It is linked to the successes of the Armed Forces on the front lines and the de-occupation of the “industrial” territories, particularly the Kharkiv region and parts of the Kherson region.

Some companies that moved abroad can become Ukraine’s “ambassadors” on foreign markets, primarily European. However, it is necessary to maintain relations with these manufacturers – if they cannot return to Ukraine, they should at least be encouraged to cooperate with Ukrainian businesses.

Legislative changes: simplifying labor relations and financial support

During martial law, lawmakers passed several laws to help businesses survive the war and support their employees.

Remote work

The reality is eventually reflected in Ukrainian legislation. With the onset of the pandemic, the concept of remote work appeared in the Ukrainian Labor Code. On July 18, 2022, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine adopted the so-called “law on freelancing,” “legalizing” freelancers’ work and enabling small and medium-sized businesses (of up to 250 employees) to officially hire them. It will be a contract with no set working hours and a salary of no more than eight times the minimum wage (currently UAH 53.6 thousand). Payment will be made for actual work time but not less than 32 hours a calendar month (i.e., employers will have to pay for 32 hours even if the freelancers work less than that).

Civil servants were prohibited from working from abroad, which led to the dismissal of 8,500 people within the first four months of the full-scale invasion. Since August, civil servants (except for category A officers) and officials of local self-government bodies (except for categories 1 to 3) can engage in other paid or entrepreneurial activities in the event of downtime or if they left before the unpaid leave. During martial law, the maximum duration of leave “at one’s own expense” for refugees and IDPs was increased from 15 to 90 days. This norm was also mainly used by civil servants and SOE employees (private enterprises settled the remote work issue by making deals with their employees). The provision regarding their mandatory presence in Ukraine should be revised to avoid losing qualified civil servants.

Greater flexibility for businesses and new opportunities for employers

When a company undergoes liquidation, reorganization, or bankruptcy in peacetime, it takes two months to dismiss an employee or three months if the company has a trade union. In wartime, employers may be unable to provide employees with jobs or good benefits. Therefore, the Verkhovna Rada allowed dismissals initiated by those employers who cannot offer their employees jobs due to the destruction of the production-related, organizational, or technical conditions, means of production, or the employers’ property as a result of the ongoing hostilities.

On July 1, the Verkhovna Rada adopted Law No. 2352-IX regulating labor relations during martial law. The law makes it possible to keep the workplace and position for the employees drafted into military service, but not their salary (which should reduce the companies’ costs).

Also, caps on the working hours of critical infrastructure facilities employees changed under martial law. For staff with reduced work hours (doctors, workers in jobs in harmful and dangerous working conditions, etc.), the maximum working time was reduced from 50 to 40 hours. Regarding the rest of the workers employed in the defense sector, in the sphere of ensuring the population’s well-being, etc., employers were given the right to increase the maximum working hours to 60 hours a week with a proportional increase in salary.

Stimulating employment

Law 2622-IX, dated September 21, 2022, abolished employment quotas for specific population categories and expanded the social services list, including individual employment planning and vouchers to obtain professional or higher education (previously, vouchers were only used for professional development). The categories of recipients of social services (including single parents and guardians) were also expanded. In addition, the law establishes the dependence of unemployment benefits on pensionable service (previously, the maximum duration of benefits was up to 360 days within two years). Greater differentiation of unemployment benefits is also established depending on the length of pensionable service. According to the new law, unemployed persons do not lose their right to unemployment benefits even if they refuse two suitable job offers from the employment service (this will increase incentives for the unemployed to sign on with the SES). However, registered unemployed people lose this status if they fail to notify the employment service of their going or staying abroad for over 14 days at a time or 60 days during the year, except for medical treatment or force majeure (this innovation will obviously not allow labor migrants to use the unemployed status). The institution of a career counselor is designed to provide services to the unemployed under individual employment plans.

According to the law, those unemployed can get a job in a subsidized position once every five years (i.e., their employer will receive reimbursement for the costs of such individuals’ salary, taking into account the caps established by the law On State Assistance). Employers can also receive compensation of up to 50% of the minimum wage for employing those without work experience (including retired service members).

Those unemployed for more than six months fall into the categories of workers for whom the employers can receive USC reimbursements (this will reduce long-term unemployment). The employers creating new workplaces and offering salaries of at least three times the minimum wage will be able to receive compensation of 50% of the USC amounts for such workplaces.

On October 15, 2022, the employment of foreigners and stateless persons and obtaining or extending the validity of employment permits for foreigners was streamlined. Foreigners and stateless persons can now work in different positions for one or more employers, given that each employer has a permit to use the labor of foreigners and stateless persons in Ukraine. In addition, foreigners can work for one employer in several positions based on one permit. The condition of the foreign employee’s salaries being at least 5 or 10 times the minimum wage to allow their employment was canceled. This administrative service will now be available at the administrative service centers. During the reconstruction, Ukraine will need a lot of labor, so attracting migrant workers should be as simple as possible.

New opportunities for the military

Law No. 2488-IX concerns the social and legal protection of military personnel and their family members (+1.5 points in the Reform Index’s 186th issue). It enshrines the rights to the social and professional adaptation of specific categories of military personnel. The adaptation comprises various levels of retraining, advanced training, and educational programs for professions that will be in demand in the labor market during the country’s reconstruction.

Financial support for enterprises

We already wrote (1, 2) about several tax benefits introduced since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Today, the Ministry of Finance proposes canceling the benefits and already has the bill ready. We support this decision because surveys of many companies show that Ukraine’s problem is not tax rates but complex administration and the tax service’s corruption. Ukraine needs defense financing, which cannot be provided at the expense of international aid.

On October 14, 2022, the government once again expanded the “5-7-9” program, enabling companies that lost their production facilities due to the war to receive recovery loans at 9% for up to 5 years in the amount of up to UAH 60 million (excluding earlier loans issued under state support programs). The fulfillment of obligations under such loans will be partly (up to 80%) ensured by a state guarantee. Overall, UAH 16 billion was allocated for the “5-7-9” program for 2023. From March to December 2022, loans worth UAH 72 billion were issued under the program.

Besides the “5-7-9” program and support with the relocation, the government provides entrepreneurs with grants under the eWork program. In 2022, the government issued 2,530 such grants worth UAH 1.6 billion.

Conclusions

The war has had an expected impact on the labor market: surveys show business closures, migration of workers, logistical problems, and the search for sales channels. Accordingly, some enterprises are forced to lay off employees and cut salaries. A significant difference between the war and previous crises (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) is the destruction of industrial and social assets (housing, schools, hospitals, etc.). Therefore, recovery will be pretty slow even after the cessation of hostilities. The war has also led to significant demographic changes, primarily emigration (mostly women and children) and loss of health and the lives of tens of thousands of people.

Overall, there will be a significant reallocation of resources in the economy and the labor market, with a considerable fall in demand for some professions and others being in short supply (e.g., in energy, construction, architecture, education, medicine, and psychology). Therefore, large-scale retraining programs for people and reintegration programs for veterans, refugees, internally displaced persons, and migrants will be needed. The work on developing such programs should begin now. However, first of all, it is necessary to create favorable conditions for investment (recovery or construction of assets), which is primarily judicial reform, simplified regulations, and the fight against corruption.

Disclaimer: This article was prepared with the financial support of the European Union. Its content is the sole responsibility of Aliona Hryshko and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations