How is Ukraine’s education coping with the war? How will it support the after-war reconstruction and what needs to be done for that?

Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, educational institutions in significant parts of Ukrainian territory that are currently or previously occupied by the Russian armed forces have been destroyed, looted, and students and teachers have been displaced or forced to attend what the occupiers refer to as ‘Russian’ schools (Figure 1). As of February 2023, 10.7% of Ukrainian educational institutions were damaged or destroyed due to the Russian aggression (Table 1). Ukrainian curricula and textbooks have been banned and even destroyed. Many kindergartens, schools and universities in the areas controlled by Ukraine have been damaged by missile or drone strikes, energy outages caused by Russian attacks on critical infrastructure, or have been affected by capacity constraints due to a large number of internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing from the occupied territories.

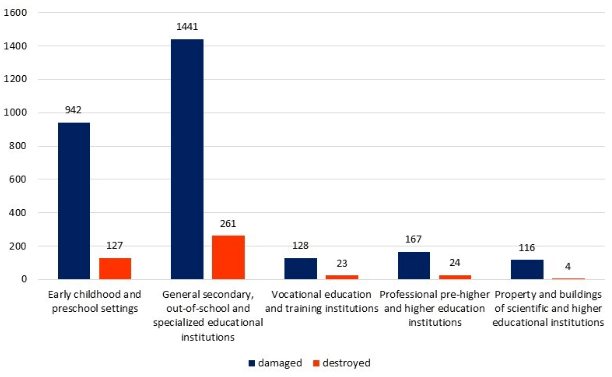

Figure 1: Damage to the Ukrainian Educational Infrastructure Due to the Russian Aggression as of February 2023

Source: Overview of the current state of education and science in Ukraine under Russian aggression, Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine.

Table 1: Ukrainian Educational Infrastructure at the End of 2021 and Damaged Due to the Russian Aggression as of February 2023

| End of 2021 | As of February 2023 | |||

| Total | Damaged | Destroyed | Total affected | |

| Kindergartens | 14 974 | 942 | 127 | 1 069 |

| Secondary schools | 13 991 | 1 441 | 261 | 1 702 |

| VET schools | 694 | 128 | 23 | 151 |

| Colleges | 283 | 167 | 24 | 191 |

| Universities | 347 | 116 | 4 | 120 |

| Total | 30 289 | 2 794 | 439 | 3 233 |

Source: Overview of the current state of education and science in Ukraine under Russian aggression, Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine.

Yet, education will play a vital role in Ukraine’s reconstruction, as it not only imparts the necessary knowledge and boosts human capital in the society, but also fosters the development of responsible, morally upright citizens who respect human rights, integrity, and accountability. It is imperative for higher education institutions to not only offer education, but also conduct research and serve as hubs for meaningful conversations on topics of societal significance. Educational institutions in the de-occupied areas have to take on an additional task of working with the mindset and trauma of the local population and possible cleavages and tensions within the de-occupied communities.

Numerous nations that have been impacted by conflicts or other similarly damaging events have indeed acknowledged the important role of education and established plans for post-conflict reconstruction and resilience. Generally, these plans recognize that education is essential to a country’s productivity, competitiveness, and innovation, as well as to its state-building and peace-building efforts (Bird, 2009; IIEP-UNESCO 2009).

Bird (2009) examines the plans for reconstruction in various countries, including Afghanistan, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Nepal, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, and Uganda. The author suggests that reconstruction programs should offer guidance to key players in the education sector, enabling them to analyze the educational system through a “conflict-sensitive lens” and develop strategies to address potential tensions. He also recommends that these programs consider the use of technology for teaching and learning, data collection and analysis, and monitoring conflict-related indicators in education policy-making, particularly in conflict or post-conflict situations.

Human capital is Ukraine’s most valuable asset, and will remain so in the future. The education system plays a critical role in creating, nurturing, and sustaining this asset. In our recent study conducted within a broader project of the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) on rebuilding Ukraine (Kahanec, Leu-Severynenko, Novosad and Stadnyi, 2022), we propose that education is a principal pillar of Ukraine’s reconstruction effort and it should be leveraged to ensure that all Ukrainian citizens are included in this effort. It will also play a crucial role in supporting statebuilding and the provision of essential state services as well as safeguarding democracy and human rights.

In line with the lessons proposed by the aforementioned studies (Bird, 2009; Ministry of Education of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, 2016; Kahanec et al. 2022), in order to prevent divisions and conflicts within the Ukrainian society and ensure that the public is fully dedicated to the processes of constructing and reconstructing the state, we argue that the education system in Ukraine must be unreservedly inclusive. In particular, it should be ready to work with veterans to support their reintegration and return to the labor market. The staff of educational institutions needs additional training so that they are ready to cope with these increased challenges. As one of the instruments for this, educational institutions can offer short-term training services.

Appropriate resources, including necessary equipment and teacher training, should be provided to ensure that all students are able to participate fully. Education institutions will also need to address the psychological trauma caused by the war, as well as the reintegration of students with multiple vulnerabilities. Special attention should be paid to reintegration of students who return from abroad – these students will have different training experience and may develop negative perception of post-war realities in Ukraine. These challenges will require support and training for both staff and students.

According to the PISA 2018 assessment (OECD, 2019; 2021), Ukrainian school children scored lower in mathematics than the OECD average. The quality of education has been further hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing war. Therefore, compensatory policies need to be put in place as soon as possible. For instance, secondary schools can offer summer or additional courses in core subjects. This requires greater flexibility in education, especially at the university level, such as allowing students to obtain a certain number of credits instead of studying for a fixed number of years to obtain a degree (Kahanec et al., 2022).

The sector of vocational education and training should strengthen the practice-based component of the training process with the help of work-based learning, practice-based training, and the elements of dual education (Kulalaieva at al., 2019). This will foster the development of education-business partnerships and provide students with better education and work prospects.

As we argue in Kahanec et al. (2022), to ensure that education reforms in Ukraine are successful in the long term, it is important to focus on the education system as a whole and strengthen its systemic synergies, rather than make sporadic, disconnected changes. Advice and training should be prioritized over overwhelming, complex regulation, and the emphasis should be on quality rather than quantity. Since 2014, improving the quality of education has been the primary objective of these reforms. This necessitates changes in the incentive structure, such as funding universities based on performance instead of student numbers, and introducing more external and internal competition, also when it comes to promotion and re-appointment of professors and appointment of academic leadership (Kahanec and Kahancová, 2019).

Additionally, educational institutions at all levels should be granted greater autonomy. The Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine must focus on policy development and establishing frameworks for quality management and control to ensure accountability to the public interest. It will be important not only to measure performance and incentivize investment, innovation, and experimentation, but also to provide the necessary resources to support quality enhancement.

To ensure that all these decentralized efforts generate synergies and reinforce each other, education in Ukraine should be developed as a comprehensive system, with reforms across secondary schools, vocational schools, colleges, and universities aligned under a single strategy with a unifying, transparent, and well-communicated mission. All levels of education should aim to help students develop their talents and choose careers based on their interests. As increased autonomy also entails greater responsibility, extensive training should be provided at all levels, including for teachers (professors), financial staff, and managerial staff of educational institutions.

Although Ukraine’s education funding is relatively high as a percentage of GDP, teacher salaries are low and equipment is often outdated or missing. It is therefore crucial to improve the efficiency of public spending on education, such as by merging educational institutions to take advantage of economies of scale. Prioritizing quality and increasing financial autonomy will make it easier for educational institutions to fundraise.

As Ukraine’s reconstruction is linked to its integration with Europe and the transatlantic partners, the education sector should focus on developing networks with foreign universities. Such collaborations would facilitate the exchange of knowledge and talent, as well as the creation of joint academic programs and research initiatives, which are essential for the reconstruction of Ukraine. Migration of Ukrainians to the EU and other countries (and back) and Ukrainian diasporas around the globe present opportunities for the creation of fruitful connections in this area.

Access to education and training plays an important role in motivating Ukrainians abroad to come back to Ukraine as soon as the hostilities of the war are over. No less important are safety and access to the labor market. Because the risk of hostilities may be present for a longer time, educational institutions should have well-equipped bomb shelters. As for the labour market access, universities and colleges may confirm qualifications of returning refugees and IDPs who lost their education documents or want to restart their professional lives. A number of Qualification Centres already provide such services.

To conclude, Ukraine’s education system is poised to confront multiple challenges in the coming years. It must first recover from the ravages of war and then fashion a comprehensive development strategy. The transformation of educational institutions must create an environment in which they can meet the country’s social and economic requirements. The education system must also improve the quality of education, foster an innovative learning and research environment, and develop partnerships with business and the civil society. Finally, it must be resolutely inclusive and collaborate with stakeholders at all levels to ensure empowerment and positive outcomes for Ukrainian people.

This essay was first published in VoxEU

References

Bird, L (2009), “Promoting resilience: developing capacity within education systems affected by conflict”, Think piece prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2011, The hidden crisis: Armed conflict and education.

IIEP-UNESCO – International Institute for Educational Planning (2009), “Rebuilding Resilience: the education challenge”, IIEP Newsletter, Vol. XXVII, No. 1.

Kahanec, M and M Kahancová (2019), “Economic research in the Visegrad countries: an insiders’ world on Europe’s periphery”, in Faces of Convergence, wiiw.

Kahanec, M, S Leu-Severynenko, A Novosad, and Y Stadnyi (2022), “Education reforms during and after the war“, in Y. Gorodnichenko, I Sologoub, and B Weder di Mauro (eds), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and policies, CEPR Press, London. https://cepr.org/chapters/education-reforms-during-and-after-war

Kulalaieva, N, S Leu (2019), “Dual education as a tool for assurance the education of sustainable development”, International Journal of Pedagogy, Innovation and New Technologies 2019 | 6(2) | 104-115, DOI 10.5604/01.3001.0013.6847 https://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.ceon.element-580e9e7e-3930-3174-8f01-056519aa6b1b

Ministry of Education of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (2016), National Education Strategic Plan (2017 – 2021).

OECD (2019), “PISA 2018 Country Note: Ukraine”.

OECD (2021), Education at a Glance 2021.

Authors: Martin Kahanec, Snizhana Leu-Severynenko, Anna Novosad, Yegor Stadnyi

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations