According to various estimates, around 6 million Ukrainian refugees are currently abroad. Most of them maintain a connection with their homeland and plan to return. Many who left in spring 2022 have already returned. Our study of the attitudes of Ukrainians remaining abroad or those who have returned helps identify factors influencing refugees’ decisions to return and their desire to do so.

In this research we used data from a survey conducted by the sociological company “Factum Group” in July-August 2023.

The main conclusions

- Of those who remained abroad at the time of the survey, 64% plan to return. Of those who returned to Ukraine, the majority want to stay in Ukraine, while only 7% plan to leave again. However, these intentions may change rather fast, and the decision to return can be spontaneous.

- 53% of adult refugees found a job abroad, 9% of them work online for a Ukrainian company, a third of them work offline in a host country. At the same time, almost 30% of those who work say that their job abroad is less qualified than their job was in Ukraine.

- About a half of school-age children, along with studies in a foreign school also attend a Ukrainian school online. For some of them a Ukrainian school online was the only form of study: this share declined from about a quarter in 2022/23 to 3% in 2023/24 (however, 2023/24 data take into account only those who stay abroad).

- We estimate three probability regression models: one for the probability that a person who fled the war returned, the second one for the probability that people who stay abroad plan to return, and the third one for the probability that a person who returned will stay in Ukraine. We include demographic factors, variables related to job and schooling for children, family factors, war pains experienced by people and a number of push and pull factors that respondents name as important for their decision-making (push factors are those that make a person exit the host country, e.g. inability to integrate; pull factors are those attracting a person to Ukraine, e.g. missing home or family).

- According to the first model, single people had more likely returned to Ukraine, while people who emigrated with husband/wife had less likely done so. Pull factors that significantly impact a person’s probability to return are missing family and home, desire that their children study in Ukraine, better job opportunities in Ukraine and having property there. Receiving from Ukrainian authorities the information that impacted their decision is a significant factor that caused people to return as well. Among push factors, the only significant one was material hardship abroad.

- Among refugees (i.e. those residing abroad at the time of the survey) those who planned to emigrate before the war and those who emigrated in February-March 2022 are less likely to have plans to return. The same is true for those with a refugee status abroad and those who have not traveled to Ukraine since February 2022. Significant pull factors that increase the probability that a person plans to return are improved safety situation, better job opportunities in Ukraine, the fact that a person misses home, wants her children to study in Ukraine and wants to participate in the recovery of Ukraine. Higher life level abroad reduces the desire to return.

- Returnees who live in the West of Ukraine more likely plan to stay – perhaps because Western regions are relatively safer. Those who intended to emigrate before the full-scale war less likely plan to stay. The same is true for those whose current welfare in Ukraine is much lower than it was abroad. If a person’s close family (parents, spouse) was in Ukraine while she was abroad, this person more likely plans to stay. Other significant factors that increase the probability to stay are that a person returned because she missed home, that she wants her children to study in Ukraine or that she wants to participate in the reconstruction.

- Ukrainians who are abroad closely follow Ukrainian news and share this information with people in the host country. They also participate in civic activities related to Ukraine – donations, volunteering, Ukraine support rallies etc. Refugee’s opinion on possible problems with reconstruction and on the necessary reforms is very similar to the opinion of people who reside in Ukraine: tackling corruption is among the top priorities.

- Ukrainian refugees should be treated not as a loss but as an asset. Many of them said that they gained new skills that can be useful for reconstruction. Government communication encouraging people to maintain ties with Ukraine and to promote Ukraine within their host countries would help both refugees and Ukraine, which needs continued support from the democratic world.

- Introduction and data description

- What factors impact the decisions to return or stay?

- Returnees vs refugees: which factors impacted the decision?

- Factors that impact the probability that a refugee plans to return

- Factors that impact the probability that a returnee plans to stay in Ukraine

- Refugees’ involvement into Ukrainian affairs

- Opinions on reconstruction and reforms

- Conclusions and policy implications

Introduction and data description

One of the most acute issues for Ukraine’s reconstruction and future development is people. Certainly the exodus of about 6 million people from Ukraine (exact numbers are not available) is a big blow to its demography and labour force. However, these people are not lost for good. Thus, CES survey of refugees (Feb. 2023) showed that three quarters of them plan to return while only 10% do not plan to return. The next wave of this survey (May 2023) showed that 63% of refugees planned to return. Opora survey of April-2023 shows that 67% of refugees would like to return to Ukraine while 18% do not plan to return. These percentages are similar to those provided by the Factum Group survey which we discuss in this article: it shows that of those who remain abroad 53% want to return while 18% do not want to return (the rest are hesitant). A reduction in the share of people who want to return may be due to the fact that people are gradually returning: the Factum Group survey shows that 63% of those who fled the war returned to Ukraine by July-August 2023 (see Box with data description for details).

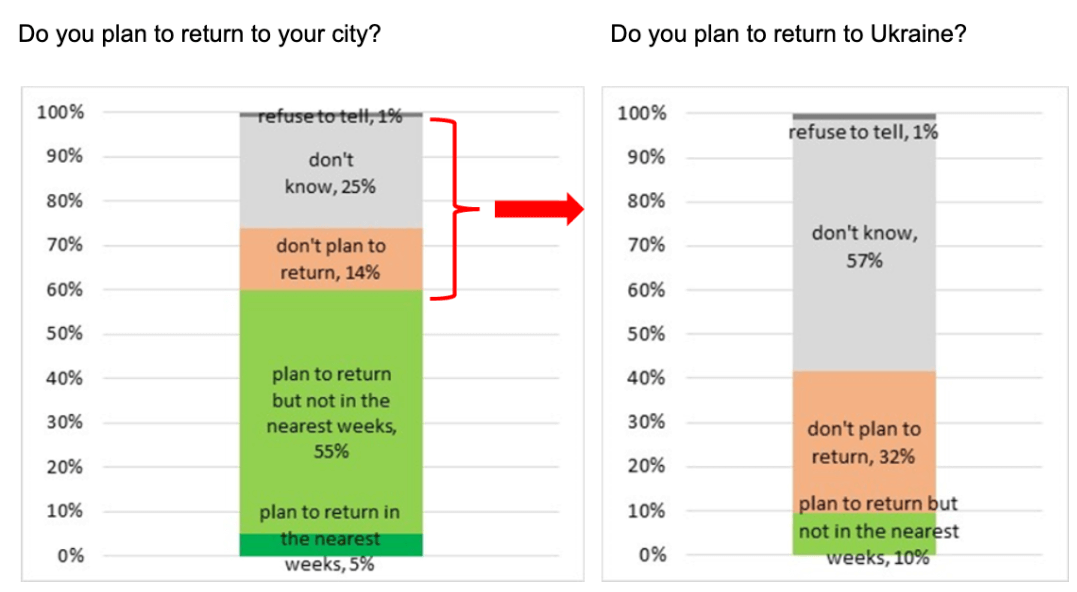

Figure 1. Share of refugees who plan or do not plan to return

Note: those who did not plan to return to their city (left panel), did not know or refused to answer this question, were asked an additional question – do you plan to return to Ukraine? Right panel represents the answers of 40% of respondents from the left panel, as shown by the bracket.

In total 64% of respondents plan to return to Ukraine, only 13% do not plan to return, and the rest are not decided. At the same time, of those who plan to return or are not sure about this 50% are not ready to return while the war goes on while 27% can return during the war if there are appropriate conditions for that, namely housing and job.

However, when interpreting this or similar surveys, one should keep in mind that the willingness or intention to return of any given person may change rather quickly. Thus, qualitative component of this survey shows that sometimes the decision to return can be spontaneous:

«I just woke up one day, bought a ticket and came home»

«…spending some time at home, I could not go back. It is better at home»

«We lived in a large house, where another family from Ukraine lived. They told us “we are going home on the 23rd. After some thinking I came to them and told “I’m going with you”»

At the same time, some refugees who returned may leave again. Their share is rather small – 7% (figure 2). 71% of those who returned were living in the same city where they lived before the full-scale war, 5% relocated within their oblast, while 24% lived in another oblast.

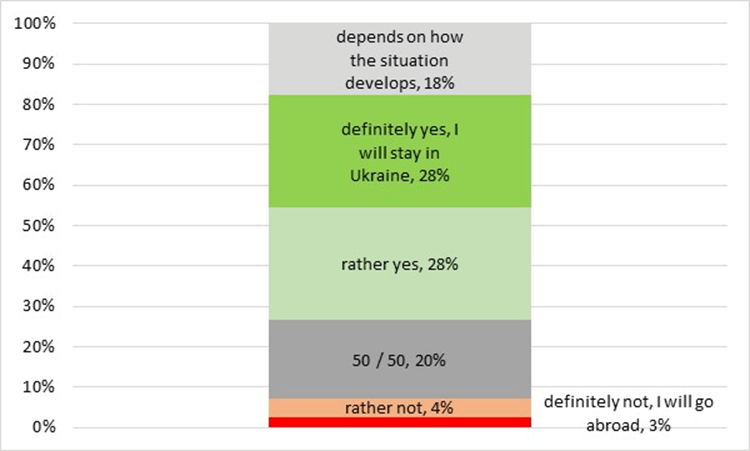

Figure 2. Do you plan to stay in Ukraine? (a question to those who returned)

There are a lot of factors that impact people’s decision to return or to stay. We analyze these factors with respect to both refugees and people who initially fled from Ukraine (the overwhelming majority in February-March 2022) but returned by the time of the survey – we call the second group returnees. We consider three regression probability models – the probability that a person stays abroad vs returned to Ukraine (at the time of the survey); the probability that a refugee plans to return, and the probability that a person who returned to Ukraine wants to stay in Ukraine. The data collection method and summary statistics are discussed in the Box.

Data description

Survey participants are people aged 18-55 who use the internet and who before the full-scale Russian invasion lived in cities with 50+ thousand people (without Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts occupied since 2014) but moved abroad. These people are divided into two target groups: those who at the moment of survey (the field work was conducted between 15th of July and 10th of August 2023) already returned to Ukraine and those who still lived abroad. Each target group includes 700 people (we deleted 18 observations on those who returned only temporarily, e.g. to solve the questions with documents). Quantitative study method is online survey (CAWI). The quota-based sample reflects the population structure of the target group in question by age, sex, region and type of settlement as of Ukrstat pre-full-scale war data (types of cities are defined as 50-100 thousand people, 100-500 thousand, 500 thousand – 1 million and over 1 million).

The sample is formed in two stages. First, the quota sample for all respondents who lived in Ukraine prior to the war is constructed. Settlement quotas are based on the question “Where did you permanently live before the war?” Second, respondents are asked “Where do you live today?” to find people who currently live abroad or those who lived abroad and returned to Ukraine. For those who live in Ukraine, an additional question is asked on whether these respondents left Ukraine because of the war since February 2022. This approach allows to estimate that among people who left because of the war 63% returned to Ukraine at the time of the survey (see presentation on returnees, slide 16).

The sample does not include people who live in Russia or Belarus.

Descriptive statistics and quotes of people from the qualitative survey can be found in the following presentations: (1) refugees, (2) opinions of refugees, (3) returnees.

About 80% of Ukrainian refugees are women, 44% of them have children, half of them are married and 20% of the total number of women left their husbands (partners) in Ukraine. The majority of people fled Ukraine soon after the full-scale war began – in February or March 2022. The majority of Ukrainian refugees stayed in Germany and Poland (about a quarter in each country), 7% in Czehchia, and other countries accepted up to 4% of the total number of refugees.

A detailed description of the survey questions can be found in Table A1 in the Annex.

What factors impact the decisions to return or stay?

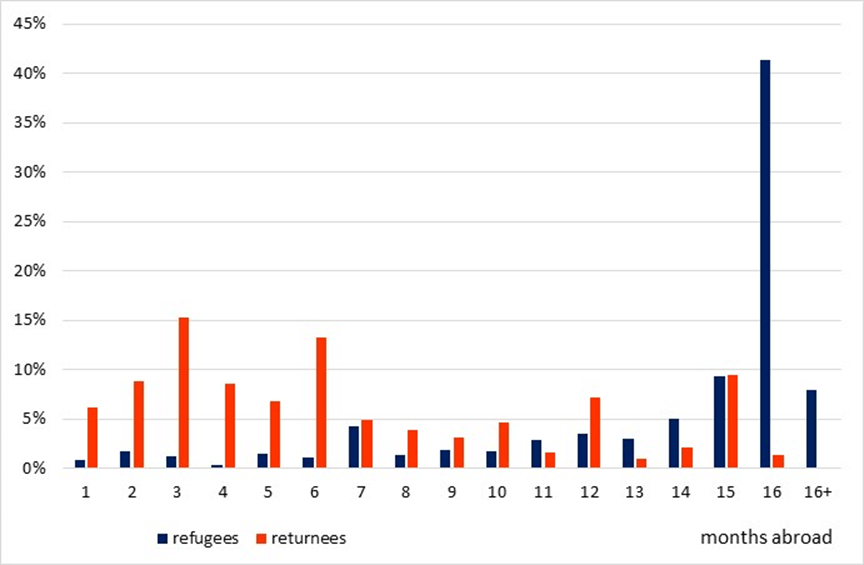

Figure 3 shows that the majority of refugees remain abroad since February-March 2022, when they fled. At the same time, people continue to leave. Most returnees have spent abroad much less time – on average 6-7 months. However, some people return to Ukraine after spending a year or more abroad.

Figure 3. Distribution of months that our respondents spent abroad by the time of the survey

Note: the percentages do not add to 100% because some respondents did not answer this question

The majority (over 80% of respondents) left their homes because of the war, and only 4% for other reasons (figure 4). People who wanted to emigrate anyway may be more likely to stay – therefore we include both the reasons and intentions to emigrate into the model. 7% of our respondents left before the full-scale invasion, 55% left in February or March 2022, and the rest of people emigrated later in 2022 or 2023.

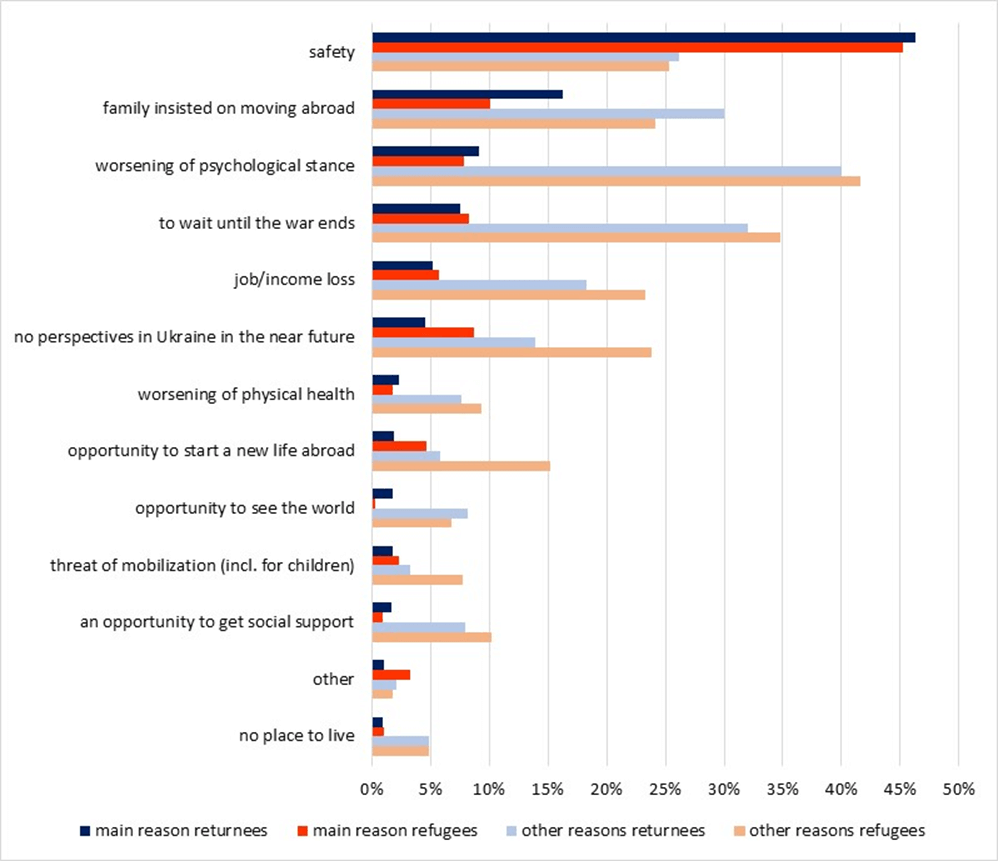

Figure 4. What were the reasons for moving abroad?

Note: blue bars are for returnees, orange for refugees, dark color denotes the main reason (a person could choose only one answer), light color – other reasons (respondent could choose several answers).

As we see from figure 4, the main reason for moving abroad was safety. It is also the main factor that prevents refugees from returning. On the other hand, refugees have many reasons to return: family, friends, and home left behind, better job prospects in Ukraine, difficulties with integration into another culture etc. We consider these factors in turn.

Family issues

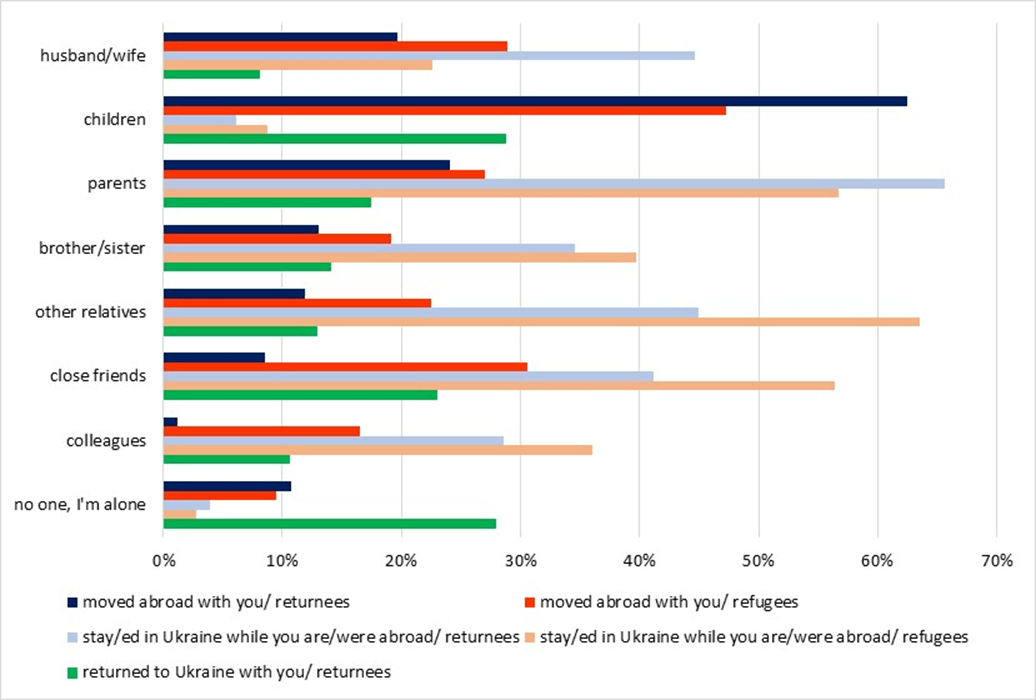

Figure 5 shows that a much larger share of people who returned had their husband or wife remaining in Ukraine while they were abroad. We also have information on relatives or friends of our respondents who are currently fighting or were fighting (figure 6). We test whether these factors impact the [fulfilled] intent to return.

Figure 5. Who of your relatives or friends moved with you abroad, stayed in Ukraine while you were abroad or returned to Ukraine with you?

Note: blue bars are for returnees, orange for refugees. The question “who returned with you?” (green bars) was asked only of returnees.

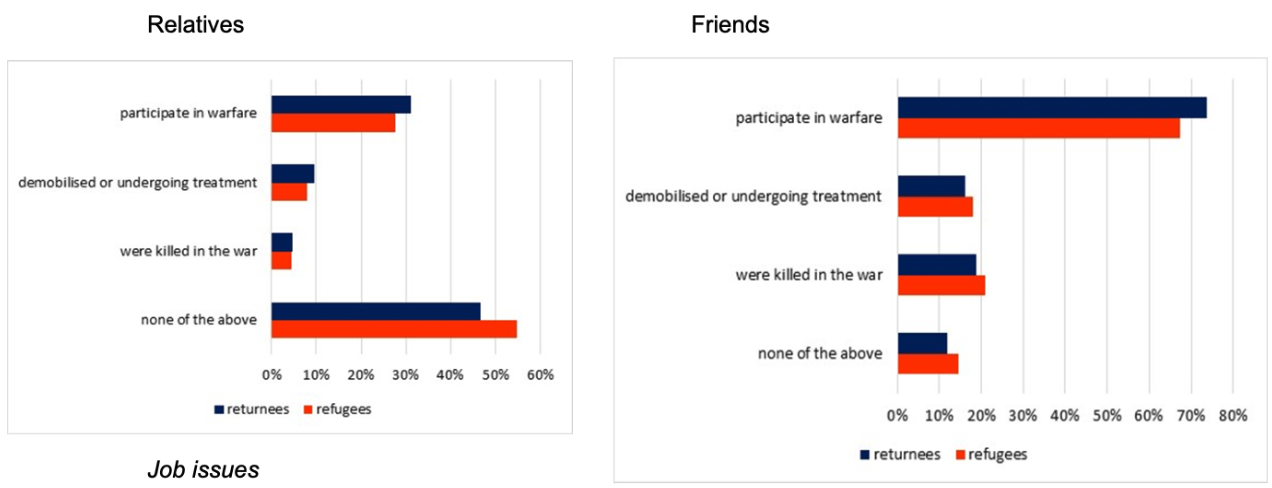

Figure 6. Do your relatives or friends participate in warfare?

Job issues

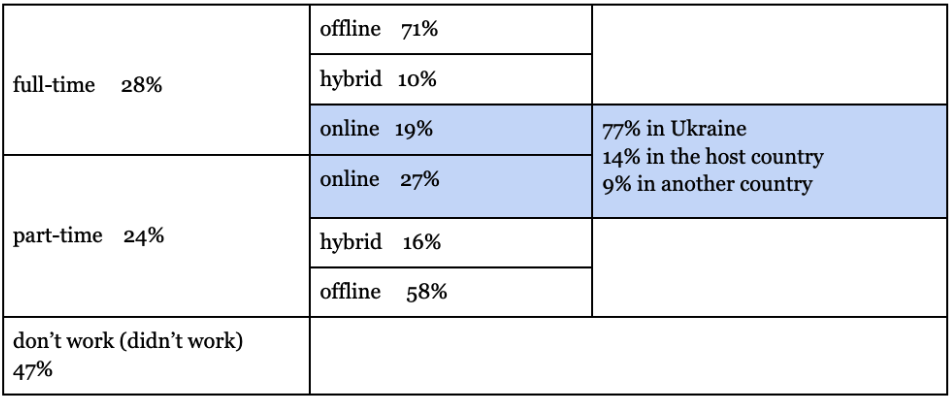

A half of refugees who worked before the war lost their job because of the war, 18% quit their job and over 30% made an arrangement with an employer to work remotely. 9% of those who stayed abroad at the time of the survey continued to work for a Ukrainian company online (table 1). Of those who worked abroad, 37% shifted to a different qualification, of them 77% entered a lower-qualified job than they had in Ukraine (table 2). 61% of those who have a job remained at the same level of qualification.

Of those who stayed abroad at the time of the survey compared to those who returned a higher share worked full-time (33% vs 23%) and also a higher share worked offline (72% vs 59% of those who worked). Theoretically, a person who continues to work for a Ukrainian organization is more likely to return while someone who works offline in a host country company is less likely to do so.

Table 1. Ukrainians who work (for refugees) or worked (for returnees) abroad

Note: each column represents the distribution for the column to the left of it. For example, among those who worked full-time, 71% worked offline, 19% worked online and 10% worked in a hybrid mode. Among those who worked online, 77% did so for a Ukrainian company

Table 2. Change in the type of work for Ukrainians who moved abroad

| work abroad →

work before the war ↓ |

military or police service | business owner / co-owner | qualified industry or service worker | CEO | department head | unqualified worker | private entrepreneur/ freelancer | specialist without subordinates |

| military or police service | 0.2 | – | 0.3 | – | – | – | – | – |

| business owner or co-owner | – | 0.8 | 0.2 | – | – | 0.1 | 0.1 | – |

| qualified industry or service worker | – | – | 18.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.0 | – | 1.1 |

| CEO | – | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.4 | – | – |

| department head | 0.2 | – | 1.5 | 0.1 | 4.5 | 3.4 | – | 0.5 |

| unqualified worker | – | – | 1.4 | – | – | 13.4 | – | – |

| private entrepreneur/ freelancer | – | – | 1.6 | – | – | 2.5 | 2.8 | 0.4 |

| specialist without subordinates | – | 0.1 | 6.4 | – | 2.1 | 10.3 | 0.4 | 20.3 |

Note: numbers in cells show percentages of the total number of respondents who worked abroad. Each number shows the share of people who moved from employment in a row to employment in a column. For example, 10.3% of respondents who worked abroad were specialists without subordinates in Ukraine (e.g. accountants, analysts) and became unqualified workers abroad. Shares of people who remained in the same position are highlighted with bold. The UNCHR survey of July 2022 showed (p.11) that 17% of refugees used to work in trade, and 17% more – in education.

Children’s studies

Among our respondents, 39% had school-age children. Of them 62% said that their children studied in a school in the host country in the 2022/23 academic year. However, only 39% reported that this was the only studying option for their children. The rest had additional studies for their children – either in a Ukrainian school online (50% of those who studied at a foreign school), or a Ukrainian school in a host country. For a quarter of refugees Ukrainian online school was the only study option of their children. A quarter reported that their children learned Ukrainian school program in some other way – on their own, with parents or tutors. For the 2023/24 academic year, this question was asked only for people who stayed abroad at the time of the survey. 34% of them had school-age children. 83% of them said that their children would study in a foreign school, of them a half – only in a foreign school, with no additional studies. 40% stated that their children would study in a Ukrainian school online, and 4.5% – that their children would study in Ukraine since they were returning home soon. For children who study Ukrainian school program while being abroad, it will be easier to adapt if they come back, thus, we include these variables into the model.

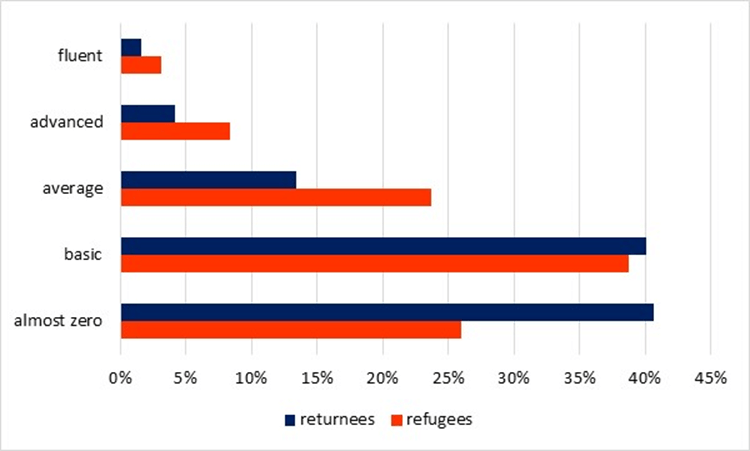

Language knowledge

Figure 7 shows that refugees know the host country language somewhat better than returnees, although 70% of them did not study this language before migration. However, among returnees a much higher share (30% vs 16%) did not study the language of the host country either in state-sponsored courses or in another way. This may indicate that these people were more determined to return in the first place.

Figure 7. How would you evaluate your knowledge of the host country language?

War pains

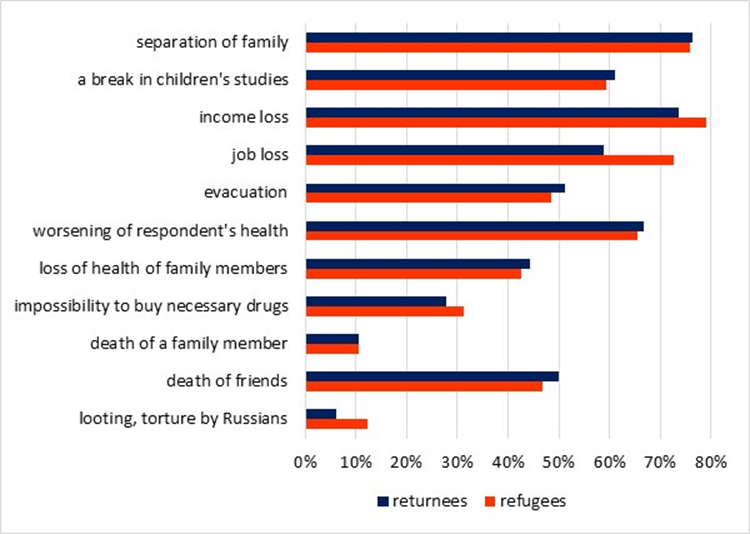

Pains experienced by refugees in Ukraine (figure 8) may play a role in preventing them from returning (e.g. one respondent said that her daughter was killed and thus it is too painful for her to return). Job loss, income loss and looting are the only factors significantly different for refugees and returnees here, but we consider other factors too.

Figure 8. Which of these did you experience?

Quality of life abroad vs in Ukraine

Other factors that may impact the decision to return or to stay are changes in the quality of different aspects of life. Figure 9 shows that the general life level in the host country for returnees was somewhat lower than for refugees. The same can be said about family relations and psychological stance. For the majority of factors, except for healthcare and psychological stance, the share of respondents who report improvement of these factors abroad compared to Ukraine is roughly equal to the share of those who report worsening of these factors (indeed, 57% of those who moved abroad indicate that they started to value Ukrainian healthcare more after they got acquainted with healthcare systems in other countries).

Figure 9. Different aspects of life abroad compared to these aspects in Ukraine before the full-scale war

Upper lines - refugees, lower lines - returnees

Returnees vs refugees: which factors impacted the decision to return?

We use the probability model (see table A2 in the Annex) to estimate which factors significantly impacted refugees’ decision to return to Ukraine. Apart from factors discussed above, we included into the regression usual demographic variables, such as sex, age, education, household size, marital status, region, income group etc. We also included the length of stay in a host country (to test a hypothesis that a longer stay in a host country decreases the probability or the desire to return) and a number of other factors (both psychological, such as missing home or family, and practical, such as better job perspectives in Ukraine or material hardship in a host country), which respondents reported as significantly impacting their decision to return.

Contrary to expectations, those who moved abroad before 2022 were more likely to return (those who relocated in February-March 2022 were also more likely to return but this may be due to the fact that the majority of Ukrainians relocated at that time). Each month spent abroad slightly increases the probability of staying.

Factors significantly increasing the probability of returning to Ukraine were missing family or home, the desire that children study in Ukraine, better job opportunities in Ukraine, return of friends to Ukraine, and having property in Ukraine (we can generally call these “pull” factors). Among “push” factors significant were feeling lonely or finding it hard to integrate abroad and feeling humiliation for living on subsidies. Such factors as feeling guilt, feeling helpless or alien to the foreign mentality, although were named by some respondents as key reasons for return, were not significant in the model.

Having parents in Ukraine, working remotely for Ukraine and improved safety in Ukraine were all significant “pull” factors, whereas material hardship abroad was a significant “push” factor. 12% of respondents stated that they received from Ukrainian authorities information that could impact their decision to return, and indeed this information significantly impacts the probability of returning.

Respondents who don't have children and those whose children studied in a foreign school in 2022/23, those who relocated with husband or wife (22% of the sample) or those whose friends relocated too are more likely to stay abroad, while non-married people are more likely to return.

Those who consider the success of reforms in Ukraine their main factor for returning are more likely to stay abroad (this may be due to the fact that reform progress has been moderate or due to the fact that these people have quite high expectations of Ukraine’s recovery). Among the war pains experienced by people the most significant is looting or other abuse by Russians - this factor increases the probability of staying. The fact that some family members or friends participate or participated in the warfare does not impact the decision to return - perhaps because the shares of such people are similar for returnees and refugees.

Factors that impact the probability that a refugee plans to return

Next we consider only those who stayed abroad at the time of the survey. We use the probability model (see table A3 in the Annex) to see which factors impact the probability that such a person plans to return to Ukraine some day (the overwhelming majority do not have a defined date of return).

Demographic factors are not significant in this model, except for family - people who migrated together with husband or wife and those who do not have children less likely plan to return.

The number of months spent abroad is not significant but perhaps its effect is captured by the variable “emigrated in February-March 2022” which negatively affects return plans. Expectedly, those who planned to emigrate before the full-scale war less likely plan to return. Those who did not travel to Ukraine since emigration and those who have a refugee protection status (these variables may be related) less likely plan to return as well.

Language and job factors turn out to be insignificant except for the fact that in the host country a person has a less qualified job than she had in Ukraine - these people more likely plan to return. Counterintuitively, those who say that subsidies which they receive from the host country are enough, also more likely plan to return compared to those for whom these subsidies are not enough (a possible explanation can be that among those for whom subsidies are not enough a higher share of people work - 54% compared to 44% among those for whom subsidies are sufficient. Although having a job abroad is not significant per se, it may indirectly impact the plans to return).

Pull factors that significantly impact a person’s plans to return are (1) the desire (of a respondent or of her children) that children study in Ukraine, (2) improved safety situation in Ukraine and hopes for peace, (3) better job perspectives in Ukraine, (4) the fact that a person misses home and (5) wants to help with the reconstruction of Ukraine. Those who are not integrated into the foreign community and those who said that their civic involvement in the host country is worse than in Ukraine also more likely plan to return (these are push factors). Higher general well-being and life satisfaction abroad expectedly reduce the desire to return.

Factors that impact the probability that a returnee plans to stay in Ukraine

As figure 2 shows, only 7% of people who returned plan to leave Ukraine again, while 56% plan to stay (the rest are hesitant). We use the probability model to estimate, which factors impact the probability that a person is willing to stay (see table A4 in the Annex).

Unlike in other models, here one of the regional variables is significant: people who live in the West more likely plan to stay - perhaps because these regions are relatively safer. Number of months spent abroad has a slight negative effect on the probability that a person plans to stay. However, the largest negative effect on this probability has the prior intent to emigrate. Those who fled for safety reasons are more likely to stay after returning to Ukraine - probably because the safety situation improved. Respondents who reported the threat of mobilization as the main reason for leaving Ukraine are more likely to stay - probably because they are not allowed to leave (however, the number of such people is very small - about 2% of the sample). Not surprisingly, if the current life level of a person in Ukraine is much lower than it was abroad, she is less likely to stay.

If a person’s parents stayed in Ukraine while she was abroad, she will be more likely to stay, if her husband or wife stayed in Ukraine, she is more likely to stay as well, but the effect is only marginally significant. Finally, people who returned are more likely to stay if they returned mainly because they missed family or home, because they wanted their children to study in Ukraine (or children wanted to study in Ukraine) or because they wanted to help with the reconstruction of Ukraine (all of these are “pull” factors).

If a person lost a friend because of the war, she is less willing to stay in Ukraine. Other war pains are not significant - probably because there are not enough observations on them.

Refugees’ involvement into Ukrainian affairs

At this stage, we can conclude that the majority of Ukrainians do not use the war as an “excuse” to emigrate. As of July-August 2023, 63% of those who fled in the previous months already returned, and 64% of those who still were abroad planned to return at some point in the future, when the safety situation in Ukraine improves.

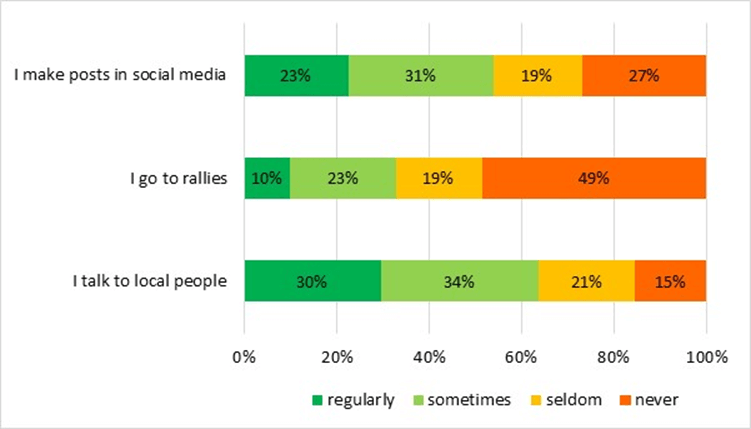

At the same time, our survey showed that Ukrainian refugees are very much involved in Ukrainian life: over 90% check the news on Ukraine several times a week or more often, about 60% check the news daily (figure 10). Major news channels for Ukrainian refugees are Telegram and other social media, as well as Ukrainian online media. As we see from figure 11, Ukrainian refugees quite actively share the information on Ukraine in their communities. This “people’s diplomacy” can be used to sustain the level of support of Ukraine among the population of Ukraine’s allies as well as to counteract Russian disinformation. 5% of our respondents indicated that they very often see Russian disinformation in the host country, and 15% stated that they sometimes run into it. In the host countries with the largest number of Ukrainians (Germany and Poland) this problem is not so acute - only 9% and 7% of those who live in these countries said that they see Russian disinformation often or sometimes. This problem is much larger in Italy, Bulgaria, Slovakia, and Czechia (over 20% of respondents residing there say that they see Russian disinformation rather often). There are not enough observations to make clear conclusions about other countries.

Figure 10. How often do you read/watch the news on Ukraine (first two bars), including from particular sources (next bars), shares of respondents, %

Note: upper lines - refugees, lower lines - returnees

Figure 11. Do you spread the information and news about Ukraine in the host country? (refugees only)

Figure 12. Activities in which Ukrainians participate (for refugees) or participated (for returnees) abroad, % of respondents

Ukrainians are quite active abroad - more than 70% donate to Ukraine, over 40% participate in rallies to support Ukraine, about 40% volunteer and about 15% participate in NGOs (figure 12). The last two numbers are lower than reported by the recent Pact/ENGAGE survey, which shows that 37% of refugees take part in an NGO and 55% are volunteers. However, current civic activity of refugees is much higher than reported by Pact/ENGAGE surveys implemented before the full-scale war, which showed that only about 4-5% of Ukrainians participated in NGOs. This suggests that the full-scale war provided a boost to civic activity in the same way as Euromaidan and the first stage of the Russian invasion did. How to make this higher level of civic activity sustainable? As NGO representatives, we can suggest that it is important to involve civil society into the official decision-making. For a greater impact, officials and civil society should complement each other rather than compete.

The survey also showed that over 70% of those who went abroad believe that their experience will be useful for the reconstruction, and over 50% think that the new skills which they gained abroad can be applied during the reconstruction. The most often mentioned are new professional skills and foreign language; also frequently mentioned are soft skills such as tolerance, better communication, and what can generally be called responsible citizenship - the habit of helping people and community, observing the rules and paying taxes etc.

Opinions on reconstruction and reforms

As we see from Figure 13, the majority of our respondents believe that until the hostilities end, full-scale reconstruction is impossible. At the same time, respondents believe that some actions useful for reconstruction, such as rebuilding houses, demining, or helping enterprises to recover, can start immediately (figure 14).

Somewhat more refugees than returnees (56% vs 48%) think that one has to wait until the end of the war and then rebuild houses according to higher standards. To the contrary, more returnees than refugees (40% vs 33%) think that reconstruction of houses should start immediately. Opinions of refugees and returnees on decentralization coincide: 60% believe that every hromada should have its tailored reconstruction plan, whereas only 30% prefer a single centralized plan for the reconstruction.

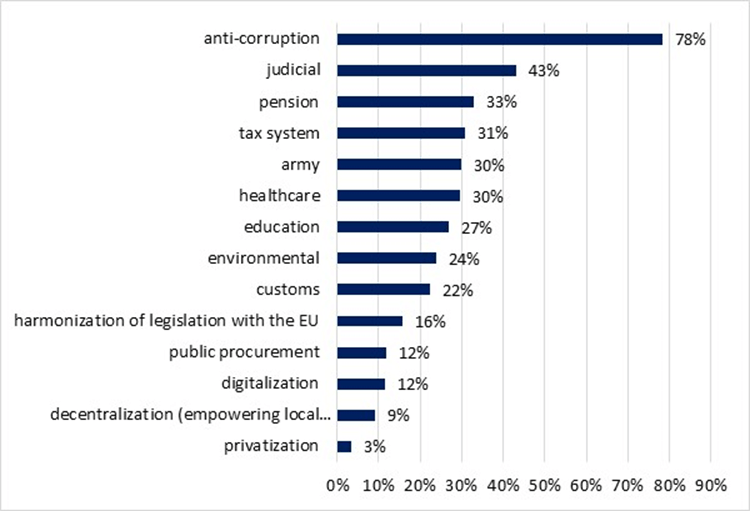

Reform priorities of our respondents (figure 15) are very similar to those named by the general Ukrainian population in the survey which we implemented last year: anti-corruption and judicial reforms are at the top of the list.

Figure 13. What do Ukrainian refugees and returnees think of reconstruction?

Upper lines - refugees, lower lines - returnees

Figure 14. What do Ukrainian refugees and returnees think of the timing of reconstruction?

Upper lines - refugees, lower lines - returnees

Figure 15. Which of the following reforms are the most important? Please select no more than 5 options

Note: both refugees and returnees answered this question

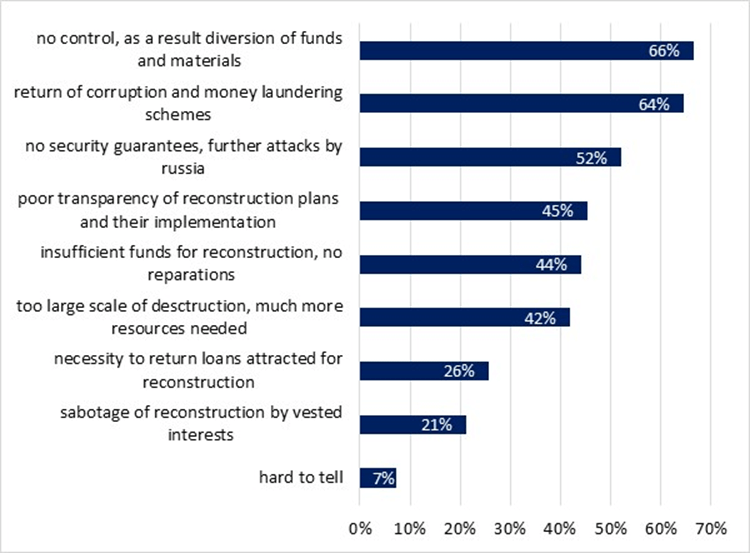

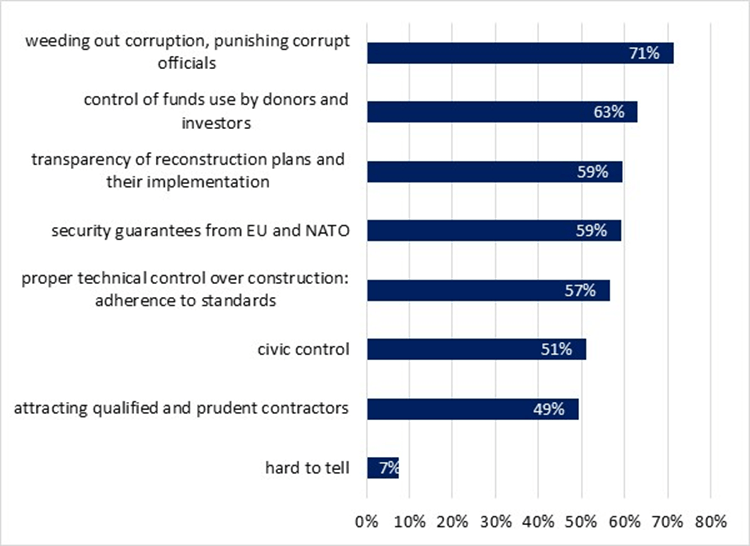

Figure 16A shows which factors, in the opinion of our respondents, could undermine reconstruction. Figure 16B mirrors it in a sense that it shows factors that would guarantee the stability of reconstruction. Quite expectedly, in the first case these factors are related to corruption and further Russian attacks, and in the second case to proper control over funds used for recovery and security guarantees.

These answers are very similar to those reported by Transparency International in their recent survey of Ukrainians who live in Ukraine. Diversion of funds and corruption are one of the largest concerns of Ukraine’s international partners too. This issue needs to be addressed. A positive signal would be suspension of officials for whom reasonable doubts about their integrity exist (for example, there is a media investigation that shows that an official may be compromised).

Figure 16A. What factors could undermine or derail reconstruction?

Note: both refugees and returnees answered this question

Figure 16B. What factors would guarantee stability of reconstruction?

Note: both refugees and returnees answered this question

Conclusions and policy implications

Our analysis showed that pull factors are much more significant for the decision and willingness to return and stay in Ukraine than push factors. Moreover, not only “personal” factors, such as missing family or home are significant, but also “societal” factors, such as willingness that children study in Ukraine or the desire to participate in reconstruction. Many of our respondents believe that during their stay abroad they gained new skills that will be useful for reconstruction.

Therefore, we suggest treating Ukrainian refugees not as a loss but as an asset. Making good use of this asset will depend not only on appropriate government policy (e.g. providing information about the situation and opportunities in Ukraine) but also on the attitude of peer citizens. Fortunately, 64% of Ukrainians do not condemn refugees and only 3% condemn them (the rest of people condemn some groups of refugees, e.g. men who fled or those who left relatively safe regions).

One specific policy that would help Ukrainian refugees return would be development of the procedure for children who studied abroad to (re)enter Ukrainian schools. Some flexibility in the curricula may be needed for that.

Meanwhile, the government could use refugees for “people’s diplomacy”- for example, ask them to distribute the news on Ukraine among their communities, donate or volunteer for Ukraine. Many refugees do this on their own but some government involvement could amplify the effect of these actions.

Policies improving life in Ukraine (most importantly defeating corruption, which would spare more resources for defeating Russia) would also raise the willingness of refugees to return.

Annex

Table A1. Questions that were asked of refugees, returnees or both

| refugees | returnees |

| Demographics: sex, age, place of living before the full-scale war, income, marital status, education, number and age of children, household size | |

| In which foreign country do you live? When did you leave Ukraine (month, year)? What was the main trigger for you leaving Ukraine? For how long have you lived/did you live in this country? | |

Did you go abroad immediately or did you stay in Ukraine for some time before going abroad?

|

|

What was the situation in your city when you left?

|

|

What is the state of your house?

|

|

| Did you have a job before the war? | |

| Who made the decision to emigrate: you, your relatives or together? What were the reasons to leave? | |

Did you have emigration plans before the full-scale war?

|

|

| Whether and when do you plan to return to your city or to Ukraine?

(do you have defined dates of return, will you return during the war; if a person does not plan to return to her city → where do you plan to return to?) |

|

| Please compare your life in Ukraine before the war and abroad (a number of factors - job, housing, education, healthcare etc.) | |

| Are you registered in the host country? | |

| Did you know the language of the host country before relocation? | |

| Do/did you learn the language of the host country? What is your language level? | |

Do/did you have a job abroad?

Did you get help with employment? |

|

| Do/did you pay rent and communal services abroad? | |

| Who of your family members lives in Ukraine and who lives abroad? | |

| Who of your family members also returned to Ukraine? | |

Do you communicate with Ukrainians who live abroad other than your family?

|

|

Did you meet Russians where you live?

|

|

Did you have contacts with the Ukrainian embassy/consulate in the host country?

Did you receive from Ukrainian embassy information that would impact your decision to return? |

|

| Did you communicate with Ukrainian NGOs? | |

| How did your children study in 2022? | |

| How will your children study since September 2023? | |

| Do you have an opportunity to leave children with someone if needed? | |

| Do you communicate with locals? | |

Are you studying?

|

Are you studying? |

| Do you have “your” doctor? | |

| Where do you find information about some support or events for Ukrainians? Do you attend those events? What kind of support do you need?

What kind of support (subsidies) do you get?

|

|

| How comfortable is/was the life in the host country for you? Please evaluate various aspects of life (housing, healthcare etc.) | |

| What are the factors that would make you return? What can Ukrainian government do for your return? | Why did you return?

What factors stimulated you to return? |

Do you want to return to Ukraine?

|

|

Have you returned to the same city?

|

|

| Is your life level now higher or lower than abroad? | |

Do you work now?

|

|

| Do you plan to stay in Ukraine? | |

| 50% of returnees and 50% of refugees (group 1): a number of questions on reconstruction and reforms in Ukraine | |

| 50% of returnees and 50% of refugees (group 1): a number of questions on civic activity abroad | |

| 50% of returnees and 50% of refugees (group 2): a number of questions on the news from Ukraine (frequency and sources; frequency of seeing Russian disinformation) | |

| 50% of refugees (group 2): a number of questions about informing the people in the host country about Ukraine | |

50% of refugees (group 2): Do you buy products of Ukrainian brands abroad?

|

|

| 50% of returnees and 50% of refugees (group 2): Do you think Ukraine will radicalize and militarize because of the war? How will the war impact Ukraine’s economy and ecology?

Which spheres in Ukraine do you value more? Do you consider your experience abroad valuable for reconstruction? Did you learn new skills that would be useful for reconstruction? What are reform priorities for you? How does the international community support Ukraine? |

|

| Have you traveled to Ukraine since the start of the full-scale war? | |

| Which language do you speak now and spoke before the full-scale war? | |

| What have you encountered because of the war? (death of relatives or friends, looting, occupation etc) | |

| Do you have family members or friends who now fight for Ukraine? | |

| What are your income sources? | |

| Do you help relatives or friends in Ukraine? | |

Table A2. Results of the Probit regressions for the probability that a person stayed abroad at the time of the survey, marginal effects

Dependent variable: =1 if a person is a refugee at the time of the survey, =0 if a person returned

| variable | dy/dx | Std. Err. | z | P>z |

| age_26_35 | 0.026 | 0.023 | 1.110 | 0.269 |

| age_36_45 | 0.035 | 0.025 | 1.370 | 0.171 |

| age_46_55 | -0.005 | 0.028 | -0.180 | 0.854 |

| not married | -0.046 | 0.024 | -1.900 | 0.057 |

| married | -0.017 | 0.022 | -0.770 | 0.443 |

| household size | -0.031 | 0.006 | -5.250 | 0.000 |

| a person doesn’t have children | 0.076 | 0.018 | 4.280 | 0.000 |

| a person relocated in Feb or March ‘22 | -0.142 | 0.013 | -10.650 | 0.000 |

| number of months abroad | 0.031 | 0.001 | 23.740 | 0.000 |

| a person relocated before 2022 | -0.304 | 0.099 | -3.050 | 0.002 |

| a person’s house is damaged | -0.075 | 0.027 | -2.790 | 0.005 |

| a person’s house is destroyed | 0.014 | 0.037 | 0.390 | 0.699 |

| a person’s house is fine | -0.050 | 0.032 | -1.580 | 0.114 |

| a person has an additional house | -0.019 | 0.042 | -0.450 | 0.656 |

| a person doesn’t have an additional house | -0.029 | 0.027 | -1.070 | 0.285 |

| did not work before the war | -0.011 | 0.021 | -0.530 | 0.593 |

| lost a job because of the war | 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.270 | 0.787 |

| quit a job because of the war | 0.085 | 0.024 | 3.470 | 0.001 |

| intended to emigrate before the war | -0.003 | 0.018 | -0.140 | 0.888 |

| housing abroad is worse than in Ukraine | 0.030 | 0.017 | 1.690 | 0.090 |

| housing abroad is better than in Ukraine | 0.019 | 0.018 | 1.060 | 0.289 |

| job abroad is worse than in Ukraine | -0.007 | 0.016 | -0.450 | 0.651 |

| job abroad is better than in Ukraine | -0.017 | 0.019 | -0.900 | 0.366 |

| relations with colleagues abroad are worse than in Ukraine | -0.006 | 0.015 | -0.400 | 0.693 |

| relations with colleagues abroad are better than in Ukraine | -0.032 | 0.018 | -1.750 | 0.081 |

| civic participation abroad is worse than in Ukraine | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.910 | 0.361 |

| civic participation abroad is better than in Ukraine | 0.003 | 0.017 | 0.170 | 0.868 |

| life in general abroad is worse than in Ukraine | -0.007 | 0.018 | -0.410 | 0.684 |

| life in general abroad is better than in Ukraine | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.820 | 0.412 |

| a person has refugee protection status | -0.040 | 0.016 | -2.460 | 0.014 |

| a person doesn’t learn host country language | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.030 | 0.975 |

| person’s knowledge of host country language is poor | -0.003 | 0.022 | -0.140 | 0.886 |

| person’s knowledge of host country language is basis | -0.018 | 0.020 | -0.900 | 0.369 |

| person’s knowledge of host country language is average (good knowledge - base category) | -0.029 | 0.023 | -1.240 | 0.215 |

| a person doesn’t/didn’t work abroad | 0.041 | 0.020 | 2.110 | 0.035 |

| a person worked online | 0.001 | 0.036 | 0.020 | 0.980 |

| a person worked online for Ukraine | -0.077 | 0.035 | -2.180 | 0.029 |

| a person worked online for a host country | -0.033 | 0.025 | -1.330 | 0.185 |

| a person’s work was less qualified than in Ukraine | -0.023 | 0.020 | -1.150 | 0.249 |

| a person continued to work distantly in the same job | 0.007 | 0.034 | 0.220 | 0.829 |

| a person pays less than market price for her house abroad (free housing - base category) | -0.006 | 0.020 | -0.290 | 0.771 |

| a person pays market price | 0.029 | 0.015 | 1.940 | 0.053 |

| husband/wife also relocated | 0.053 | 0.020 | 2.730 | 0.006 |

| parents also relocated | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.830 | 0.406 |

| brother/sister also relocated | 0.031 | 0.020 | 1.580 | 0.115 |

| other relatives also relocated | 0.031 | 0.017 | 1.810 | 0.070 |

| friends also relocated | 0.116 | 0.018 | 6.570 | 0.000 |

| husband/wife stayed in Ukraine | 0.009 | 0.019 | 0.490 | 0.626 |

| parents stayed in Ukraine | -0.062 | 0.015 | -4.090 | 0.000 |

| brother/sister stayed in Ukraine | -0.009 | 0.013 | -0.660 | 0.510 |

| other relatives stayed in Ukraine | 0.049 | 0.015 | 3.340 | 0.001 |

| friends stayed in Ukraine | 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.460 | 0.647 |

| a person received from Ukrainian government information that impacted her decision | -0.098 | 0.026 | -3.830 | 0.000 |

| in 2022 children studied at school abroad | 0.075 | 0.016 | 4.660 | 0.000 |

| in 2022 children studied in Ukrainian school online | 0.010 | 0.016 | 0.610 | 0.540 |

| Main factors that impacted or could impact a person’s decision (a person could select only one factor) | ||||

| a person misses family | -0.248 | 0.023 | -10.660 | 0.000 |

| a person misses friends | -0.093 | 0.069 | -1.340 | 0.179 |

| a person feels lonely | -0.226 | 0.028 | -8.000 | 0.000 |

| a person misses home | -0.187 | 0.023 | -8.280 | 0.000 |

| a person feels humiliated because she lives on subsidies | -0.109 | 0.037 | -2.970 | 0.003 |

| it is hard to integrate in a foreign country | -0.183 | 0.036 | -5.130 | 0.000 |

| it is easier to find a job in Ukraine or the job is better | -0.107 | 0.024 | -4.480 | 0.000 |

| a person has real estate or other property in Ukraine | -0.288 | 0.056 | -5.170 | 0.000 |

| children wanted to return to Ukraine or a person wanted children to study in Ukraine | -0.133 | 0.024 | -5.660 | 0.000 |

| success of reforms in Ukraine | 0.338 | 0.069 | 4.880 | 0.000 |

| a person’s friends returned to Ukraine | -0.174 | 0.050 | -3.470 | 0.001 |

| a person wants to help with renovation of Ukraine | -0.061 | 0.046 | -1.330 | 0.184 |

| safety in Ukraine improved | -0.053 | 0.022 | -2.360 | 0.018 |

| a person feels material hardship abroad | -0.049 | 0.022 | -2.220 | 0.027 |

| Scars of war that a person experienced | ||||

| loss of job | 0.000 | 0.017 | -0.020 | 0.985 |

| loss of income | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.290 | 0.768 |

| evacuation | -0.049 | 0.014 | -3.430 | 0.001 |

| looting | 0.077 | 0.022 | 3.440 | 0.001 |

| break in children’s studies | 0.029 | 0.014 | 2.090 | 0.037 |

| deterioration of health | 0.031 | 0.015 | 2.080 | 0.037 |

| could not get life-saving medicines | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.580 | 0.565 |

| family breakup | 0.054 | 0.016 | 3.270 | 0.001 |

| health of family member(s) deteriorated | -0.026 | 0.014 | -1.830 | 0.068 |

| loss of a family member | -0.051 | 0.023 | -2.170 | 0.030 |

| loss of friend | -0.010 | 0.013 | -0.760 | 0.447 |

number of observations: 1407, Pseudo R2=0.7338, Prob>chi2=0.000

bold font indicates results significant at 5% level

Table A3. Results of the probit regression for the variable “a person plans to return to Ukraine” (for refugees only), marginal effects

| independent variables | dy/dx | Std. Err. | z | P>z |

| male | -0.007 | 0.053 | -0.120 | 0.902 |

| a person has secondary education | 0.121 | 0.075 | 1.610 | 0.107 |

| a person has professional education (higher or more - base category) | -0.016 | 0.042 | -0.370 | 0.712 |

| household size | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.110 | 0.909 |

| a person doesn’t have children | -0.069 | 0.035 | -1.960 | 0.050 |

| a person relocated in Feb or March 2022 | -0.113 | 0.046 | -2.440 | 0.015 |

| number of months spent abroad | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.780 | 0.436 |

| did not work before the war | 0.108 | 0.059 | 1.810 | 0.070 |

| lost a job because of the war | 0.067 | 0.054 | 1.250 | 0.213 |

| quit a job because of the war | -0.017 | 0.062 | -0.280 | 0.780 |

| before the war a person intended to emigrate for good | -0.140 | 0.041 | -3.390 | 0.001 |

| civic participation abroad is worse than in Ukraine | 0.097 | 0.037 | 2.600 | 0.009 |

| civic participation abroad is better than in Ukraine | -0.044 | 0.041 | -1.070 | 0.283 |

| healthcare abroad is worse than in Ukraine | 0.031 | 0.039 | 0.780 | 0.434 |

| healthcare abroad is better than in Ukraine | 0.098 | 0.043 | 2.260 | 0.024 |

| life in general abroad is worse than in Ukraine | -0.036 | 0.047 | -0.760 | 0.448 |

| life in general abroad is better than in Ukraine | -0.122 | 0.041 | -2.960 | 0.003 |

| a person has a refugee protection status abroad | -0.131 | 0.044 | -2.960 | 0.003 |

| before moving abroad, a person had a good knowledge of host country language | 0.124 | 0.069 | 1.800 | 0.071 |

| before moving abroad, a person had a medium knowledge of host country language (did not know the language - base category) | 0.030 | 0.043 | 0.710 | 0.479 |

| a person doesn’t learn host country language | 0.005 | 0.055 | 0.090 | 0.930 |

| person’s knowledge of host country language is poor | 0.115 | 0.063 | 1.830 | 0.067 |

| person’s knowledge of host country language is basis | -0.002 | 0.054 | -0.030 | 0.973 |

| person’s knowledge of host country language is average (good knowledge - base category) | -0.028 | 0.056 | -0.500 | 0.616 |

| a person doesn’t work abroad | 0.021 | 0.043 | 0.490 | 0.627 |

| person’s job abroad is less qualified than in Ukraine | 0.124 | 0.047 | 2.660 | 0.008 |

| a person continues to work in her previous job distantly | 0.045 | 0.090 | 0.500 | 0.618 |

| husband/wife also relocated | -0.116 | 0.042 | -2.760 | 0.006 |

| parents also relocated | 0.041 | 0.042 | 0.990 | 0.323 |

| husband/wife stays in Ukraine | 0.042 | 0.043 | 0.990 | 0.324 |

| parents stay in Ukraine | 0.019 | 0.036 | 0.540 | 0.591 |

| children stay in Ukraine | 0.105 | 0.073 | 1.440 | 0.149 |

| a person doesn’t communicate with local citizens | 0.102 | 0.036 | 2.840 | 0.005 |

| payments and subsidies that a person receives abroad are sufficient | 0.105 | 0.039 | 2.710 | 0.007 |

| payments and subsidies that a person receives abroad are partially sufficient (not sufficient - base category) | -0.014 | 0.038 | -0.370 | 0.712 |

| how comfortable do you feel in general in the host country? (1 to 5 where 5 is the most comfortable) | -0.101 | 0.021 | -4.790 | 0.000 |

| Main factors that impacted or could impact a person’s decision (a person could select only one factor) | ||||

| a person misses family | 0.188 | 0.140 | 1.340 | 0.179 |

| a person misses friends | 0.363 | 0.207 | 1.760 | 0.079 |

| a person feels lonely | 0.200 | 0.148 | 1.360 | 0.175 |

| a person misses home | 0.348 | 0.141 | 2.460 | 0.014 |

| it is hard for a person to integrate abroad | -0.016 | 0.177 | -0.090 | 0.928 |

| it is easier to find a job in Ukraine or the job is better | 0.328 | 0.107 | 3.080 | 0.002 |

| children want to return to Ukraine or a person wants children to study in Ukraine | 0.534 | 0.125 | 4.260 | 0.000 |

| economic situation in Ukraine improves | 0.143 | 0.108 | 1.330 | 0.185 |

| success of reforms in Ukraine | 0.073 | 0.102 | 0.710 | 0.475 |

| a person would like to help with reconstruction of Ukraine | 0.371 | 0.183 | 2.030 | 0.042 |

| safety in Ukraine improves | 0.319 | 0.116 | 2.760 | 0.006 |

| a person experiences material hardship | 0.041 | 0.096 | 0.430 | 0.666 |

| peace is established in Ukraine | 0.196 | 0.086 | 2.290 | 0.022 |

| other factors | ||||

| a person did not travel to Ukraine while living abroad | -0.071 | 0.034 | -2.110 | 0.035 |

| a person’s family member(s) is/ are in combat | -0.094 | 0.056 | -1.680 | 0.094 |

| a person’s family member(s) is/ are in demobilized or undergoing treatment | -0.109 | 0.067 | -1.630 | 0.103 |

| a person’s family member(s) were killed | -0.134 | 0.080 | -1.690 | 0.091 |

| a person’s family member(s) is/ are not fighting | -0.159 | 0.057 | -2.800 | 0.005 |

| a person’s friend(s) is/ are in combat | 0.143 | 0.044 | 3.230 | 0.001 |

| a person’s friens(s) is/ are in demobilized or undergoing treatment | -0.021 | 0.046 | -0.470 | 0.637 |

| a person’s friend(s) were killed | 0.106 | 0.040 | 2.630 | 0.008 |

| a person’s friend(s) is/ are not fighting | 0.134 | 0.061 | 2.210 | 0.027 |

number of observations: 658, Pseudo R2=0.307, Prob>chi2=0.0

bold font indicates results significant at 5% level

Table A4. Results of the probit regression for the variable “a person plans to stay in Ukraine” (for returnees only), marginal effects

| independent variables | dy/dx | Std. Err. | z | P>z |

| male | -0.005 | 0.053 | -0.100 | 0.919 |

| age | -0.006 | 0.014 | -0.450 | 0.650 |

| age2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.350 | 0.728 |

| East | 0.020 | 0.056 | 0.350 | 0.727 |

| West | 0.178 | 0.067 | 2.660 | 0.008 |

| Center & North (South - base category) | 0.056 | 0.053 | 1.040 | 0.296 |

| a person relocated in Feb or March 2022 | 0.066 | 0.036 | 1.870 | 0.061 |

| number of months spent abroad | -0.011 | 0.004 | -2.760 | 0.006 |

| a person relocated before 2022 | 0.154 | 0.110 | 1.400 | 0.161 |

| main reason for relocation - house was ruined | 0.504 | 0.238 | 2.120 | 0.034 |

| main reason for relocation - lower income | 0.226 | 0.144 | 1.570 | 0.116 |

| main reason for relocation - safety | 0.273 | 0.127 | 2.160 | 0.031 |

| main reason for relocation - no perspectives in Ukraine | 0.089 | 0.148 | 0.600 | 0.547 |

| main reason for relocation - negative emotions because of the war | 0.226 | 0.131 | 1.720 | 0.086 |

| main reason for relocation - necessity to obtain treatment | 0.143 | 0.174 | 0.820 | 0.411 |

| main reason for relocation - to start a new life abroad | 0.203 | 0.166 | 1.220 | 0.222 |

| main reason for relocation - family insisted on relocation | 0.321 | 0.129 | 2.490 | 0.013 |

| main reason for relocation - wait until the war is over | 0.241 | 0.137 | 1.760 | 0.079 |

| main reason for relocation - an opportunity to obtain social support abroad | 0.190 | 0.225 | 0.840 | 0.399 |

| main reason for relocation - to avoid mobilization | 0.708 | 0.214 | 3.310 | 0.001 |

| main reason for relocation - better job perspectives abroad | 0.343 | 0.272 | 1.260 | 0.208 |

| a person rather did not plan to emigrate before the war | -0.098 | 0.039 | -2.540 | 0.011 |

| a person rather planned to emigrate before the war | -0.214 | 0.054 | -3.940 | 0.000 |

| a person planned to emigrate before the war (definitely did not plan to emigrate - base category) | -0.404 | 0.117 | -3.440 | 0.001 |

| husband/wife stayed in Ukraine while a person was abroad | 0.072 | 0.039 | 1.830 | 0.068 |

| parents stayed in Ukraine while a person was abroad | 0.074 | 0.036 | 2.050 | 0.040 |

| children stayed in Ukraine while a person was abroad | -0.117 | 0.075 | -1.560 | 0.119 |

| no family stayed in Ukraine while a person was abroad | 0.187 | 0.103 | 1.810 | 0.071 |

| husband/wife returned with a person to Ukraine | 0.021 | 0.067 | 0.310 | 0.755 |

| parents returned with a person to Ukraine | -0.010 | 0.048 | -0.210 | 0.836 |

| children returned with a person to Ukraine | -0.052 | 0.045 | -1.160 | 0.246 |

| brother or sister returned with a person to Ukraine | -0.101 | 0.047 | -2.120 | 0.034 |

| other relatives returned with a person to Ukraine | 0.148 | 0.051 | 2.900 | 0.004 |

| friends returned with a person to Ukraine | 0.003 | 0.046 | 0.060 | 0.949 |

| colleagues returned with a person to Ukraine | 0.075 | 0.053 | 1.400 | 0.162 |

| no one returned with a person to Ukraine | -0.076 | 0.053 | -1.420 | 0.157 |

| a person lives in the same city as before the war | 0.010 | 0.042 | 0.230 | 0.819 |

| compared to life abroad, life level of a person in Ukraine is much lower | -0.173 | 0.051 | -3.360 | 0.001 |

| compared to life abroad, life level of a person in Ukraine is lower | -0.075 | 0.042 | -1.790 | 0.073 |

| compared to life abroad, life level of a person in Ukraine is higher | 0.046 | 0.048 | 0.950 | 0.340 |

| compared to life abroad, life level of a person in Ukraine is much higher (the same - base category) | 0.095 | 0.099 | 0.960 | 0.338 |

| a person doesn’t work after returning | -0.047 | 0.035 | -1.350 | 0.178 |

| Main factors that impacted or could impact a person’s decision to return (a person could select only one factor) | ||||

| a person missed family | 0.111 | 0.051 | 2.160 | 0.030 |

| a person missed friends | -0.173 | 0.209 | -0.830 | 0.409 |

| a person felt lonely | 0.071 | 0.069 | 1.020 | 0.309 |

| a person missed home | 0.210 | 0.051 | 4.140 | 0.000 |

| a person felt guilty for being outside Ukraine | 0.022 | 0.163 | 0.130 | 0.894 |

| a person felt humiliated for living on subsidies | 0.033 | 0.143 | 0.230 | 0.819 |

| it was hard for a person to integrate abroad | 0.049 | 0.092 | 0.530 | 0.594 |

| job perspectives in Ukraine are better | 0.017 | 0.088 | 0.200 | 0.844 |

| healthcare in Ukraine is better | 0.256 | 0.126 | 2.030 | 0.042 |

| a person owns a house or other real estate | 0.050 | 0.088 | 0.570 | 0.571 |

| children want to return to Ukraine or a person wants children to study in Ukraine | 0.149 | 0.073 | 2.030 | 0.043 |

| friends of a person returned to Ukraine | -0.152 | 0.170 | -0.900 | 0.370 |

| a person wants to help with reconstruction of Ukraine | 0.287 | 0.102 | 2.830 | 0.005 |

| safety in Ukraine improved | 0.238 | 0.072 | 3.300 | 0.001 |

| Other factors | ||||

| a person’s family member is in the army | 0.076 | 0.053 | 1.430 | 0.152 |

| a person’s family member is demobilized or undergoing treatment | 0.075 | 0.063 | 1.190 | 0.234 |

| a person’s family member was killed | 0.046 | 0.080 | 0.570 | 0.568 |

| a person’s family members do not participate in the war | 0.076 | 0.053 | 1.430 | 0.153 |

| a person lost a job because of war | 0.059 | 0.035 | 1.660 | 0.097 |

| a person lost a friend because of war | -0.076 | 0.037 | -2.070 | 0.039 |

| a person’s friend is in the army | 0.055 | 0.051 | 1.070 | 0.284 |

| a person’s friend is demobilized or undergoing treatment | 0.150 | 0.049 | 3.030 | 0.002 |

| a person’s friend was killed | -0.079 | 0.045 | -1.750 | 0.080 |

| a person’s friends do not participate in the war | 0.042 | 0.072 | 0.580 | 0.562 |

number of observations: 732, Pseudo R2=0.215, Prob>chi2=0.0

bold font indicates results significant at 5% level

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations