As Western democracies apparently struggle to find internal resources to help Ukraine defeat Russian aggression, a mountain of Russian assets sits frozen in various locations in Europe, North America and elsewhere. Apart from the frozen $300 billion of the Russian central bank, Russia’s assets hidden abroad can amount to as much as $1.1 trillion. Is it the time to seize Russian money?

To answer this question, one has to weigh pros and cons as well as consider alternatives.

Seizing Russian assets hits two birds with one stone: 1) it punishes Russia’s aggression; 2) it gives Ukraine resources to defend itself. One can achieve the first objective by imposing crippling economic sanctions and isolation on Russia. This route has been explored but the enforcement of the sanctions has been rather weak. As a result, Russia still receives about

€700 million a day from fossil fuel exports and sells the majority of its oil at above the price cap that was established despite harsher suggestions such as “oil-for-food” or “take-don’t-pay” schemes.

For the second objective, Western governments can raise taxes or loan money to prop up Ukraine. The fiscal option faces an uphill battle in the US Congress and other national parliaments. Lending money to Ukraine is a challenge too (especially for multilateral organizations such as the International Monetary Fund) because Ukraine is unlikely to repay its debts in full after the war.

So if the alternatives do not look attractive, what are the costs and benefits of seizing Russian assets?

First, on December 22nd, Russia threatened to cut diplomatic ties with the US if the States confiscate frozen Russian assets. Whether this threat is realistic or not is unclear. For example, Russia complained about the frozen assets but did not cut diplomatic ties. On the other hand, these threats suggest that, unlike human life, money is something that the Russian regime cares about. This means leverage over Putin and his cronies.

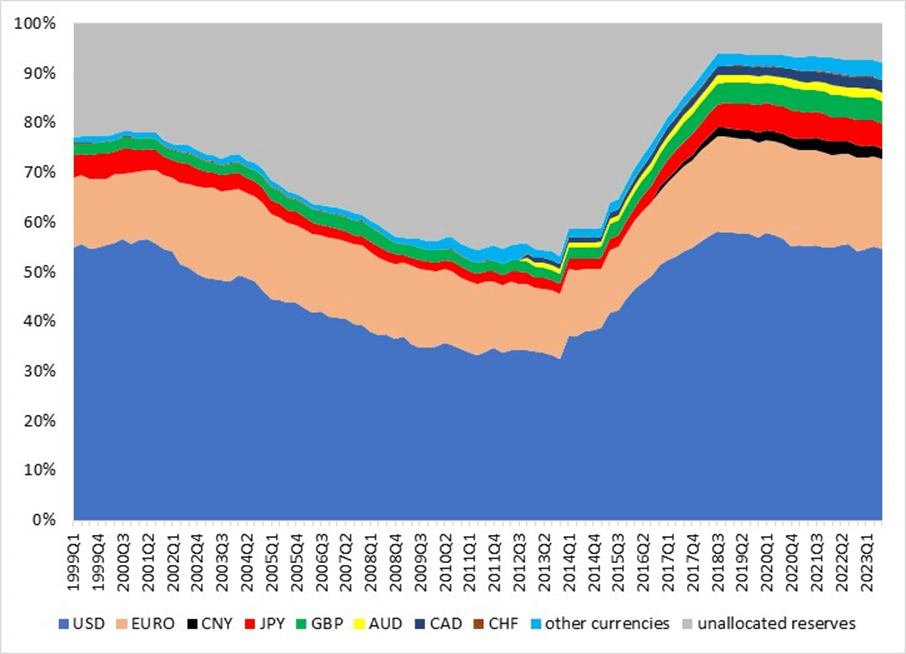

Second, there is a concern that the US dollar and (especially) the euro can lose their reserve currency status. This concern is far-fetched because there is no viable alternative to the current major reserve currencies now or in the foreseeable future. Indeed, the dollar and the euro dominate in the global trade and financial markets. 86% of the world central bank reserves are kept in “Western” currencies (with 59% in USD) compared to about 2% in renminbi (Figure 1). Neither China nor the developing world provide similarly low-risk investment opportunities, high-quality legal infrastructure, or abundant liquidity. If all the countries that hold the dollar, euro, yen or pound in their reserves try to sell these assets, where would they go?

Figure 1. Currency composition of central bank reserves worldwide

Source: IMF data

Furthermore, we already know that it is unrealistic to expect that the confiscation would prompt a run on the dollar or the euro. Russia lost access to its assets almost two years ago but this has had no impact on global financial and commodity markets. In 2022, the US government seized Afghan government assets after the Taliban took power and the dollar did not lose its privileged status. The US government seized German assets twice in the 20th century and these actions did not undermine confidence in the dollar. Hence, the economic and financial risks of confiscation are grossly overstated.

Third, some are concerned that Russia can confiscate assets of Western companies that still operate there. However, it is a sunk cost as Russia will confiscate them anyway sooner or later. If this confiscation happens sooner, Raiffeisen Bank, Nestle and the likes will pay less taxes to the aggressor’s budget and thus contribute less to the Russian aggression. Moreover, assets of Russian private companies and oligarchs abroad can be confiscated in retaliation to compensate for some losses.

Fourth, the specter of German resentment about post-WWI reparations haunts some policymakers as they fear that somehow extracting compensation from Russia can lead to another round of aggression in the future. But this is a wrong inference from that experience. Many countries ranging from Finland to Iraq had to pay reparations after wars in the 20th century and they did not launch new wars. So it was undefeated German militarism rather than reparations themselves that led to WWII. Furthermore, reparations imposed on Germany were a flow cost while seizing Russian money is taking over a stock of funds that are already outside of Russian control. Hence, if a democratic government somehow emerges in Russia (which is a big if), it will not be affected by seizing Russian assets now.

Fifth, consider the cost of not helping Ukraine and thus letting Russia win. For example, suppose Russia is on the border of Poland, Romania, Hungary. What is the cost of military build-up to contain aggressive Russia? Will NATO intervene if Russia occupies several Russian-speaking cities of Latvia or Estonia or if it sends migrants with weapons to storm the Finnish border? What would destabilize financial markets and the economy more – confiscation of frozen Russian assets or a full-scale war between the “axis of evil” and NATO? The costs could be staggering: during the height of the Cold War, the US alone spent close to 10% of its GDP on defense which amounts to $2.3 trillion per year. If NATO countries do not want direct confrontation, they should be much more serious about giving resources to Ukraine and denying resources to Russia.

Finally, one may object here that confiscation of Russian assets would undermine the rule of law. However, rule of law is about fairness as much as protection of property. Russia launched a war of aggression, it continues to destroy cities and kill scores of civilians in Ukraine, Russia ruins international law. What does it take to say enough is enough and start meeting out justice? Confiscation of Russian assets would strengthen rather than undermine the rule of law.

In summary, the case for not seizing Russian assets is weak. Until now Russia was able to reap the benefits of its aggression and levy losses on the developed countries (e.g. they had to handle refugee crises when Russia destroyed Syria and invaded Ukraine). This is an absurd state of affairs. The aggressor must be held accountable and it must start paying for its crimes now. This will be a first step to restoring justice without which a long-lasting peace is impossible.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations