“When the war broke out in 2014, we initiated reforms in the army. With the onset of the pandemic, we intensified our efforts toward healthcare reform. But what needs to happen for us to prioritize sufficient funding for teachers? This quote is from one of the films of the “New National Idea” series by Mykhailo Bno-Ayriyan. Education is the cornerstone of societal development and a critical element for the success of future reforms. What’s happening with funding its key link – secondary education – i.e., schools where young Ukrainians spend the formative ten years? What changes have taken place recently? Will there be enough funds to provide adequate salaries for all teachers? And most importantly, have financing mechanisms become more equitable to achieve the state’s goals of ensuring holistic development, education, character building, talent identification, and socialization of individuals?”

Since 2014, the state has gradually transferred the responsibility of organizing general secondary education to the local level. As of 2021, this responsibility falls on the communities. Following the completion of the primary phase of administrative-territorial reform (i.e., the local elections on October 25, 2020), Ukraine now has 1,469 territorial communities. One hundred thirty-six districts were created with considerably reduced powers and budgetary resources instead of the previous 490 districts.

Naturally, when the state delegates the responsibility of providing high-quality secondary education to local authorities, it also provides them with a specific financial resource to do so. This resource is directly allocated from the state budget to the budgets of territorial communities, bypassing the regional distribution level, unlike most other inter-budgetary transfers. Subventions are inter-budgetary transfers with a clearly defined purpose (unlike subsidies, which can be distributed at the recipient’s discretion). The Budget Code of Ukraine has a dedicated article (Article 103-2) outlining the educational subvention’s purpose. According to this article, the subvention can be used to pay for teaching staff salaries in various types of educational institutions, such as primary schools, gymnasiums, lyceums, special schools, inclusive resource centers, and so on.

The educational subvention provided to communities can only be utilized to pay pedagogical staff salaries. Financing for technical staff, utility payments, maintenance, repairs, and school development must come from the community’s own revenues. Subvention balances, which refer to the unspent subvention amount, usually remain with the communities. These balances can be used for other education-related purposes, such as developing base schools, providing personal computers and multimedia equipment for educational institutions, implementing measures to ensure fire safety, repairing and purchasing equipment for canteens (food blocks) in general secondary education institutions, connecting educational institutions to the Internet (mainly in rural areas), etc.

In the wake of the great war, the communities could use the remainder of their educational subvention from the beginning of 2022 to provide aid to IDPs and accommodate them, as the directions of using the subvention were expanded to cover this need. However, in 2023, the residuals from previous years were reclaimed from the communities and returned to the state budget. The directions of use for these funds were somewhat restricted due to the limitations imposed by martial law (Resolution No. 590), which prevented certain expenditures, mainly capital ones. Nonetheless, the funds could still be used to purchase school buses, which were in shorter supply in the communities due to the war. Many communities took advantage of this opportunity.

Apart from the educational subvention, communities could traditionally obtain funds from the State Regional Development Fund or socio-economic subvention to finance their schools (however, we are advocating the abolition of the latter as politically motivated).

On an annual basis, the law on the state budget determines the educational subvention amount allocated to all its beneficiaries – regional budgets (which fund some specialized schools, lyceums, and boarding schools) as well as the budgets of territorial communities. The distribution of the subvention is determined by a formula developed by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine and approved by the Cabinet of Ministers.

The primary factors taken into consideration in the formula include the following:

- the number of students who complete general secondary education;

- anticipated class size;

- educational plans (such as the number of lessons in various subjects for each class, a grouping of classes, etc.)

The basis for distributing the educational subvention among local budgets includes several factors:

- the estimated financial standard of budgetary security (funding needed to ensure the pedagogical component of education for primary school students in a general secondary education institution in Kyiv);

- the contingent of students as of September 5 of the year preceding the planned budget period;

- the curriculum (class divided into groups, complete classes, etc.);

- salaries (e.g., with average teacher wages of UAH 204.82 thousand per year or UAH 17.1 thousand per month in 2023, UAH 206.38 thousand/UAH 17.2 thousand in 2022, and UAH 190.38 thousand / UAH 16.5 thousand in 2021);

- adjusting coefficients (taking into account variables such as the proportion of the rural population in the community and the student density, etc.).

What does it look like in practice?

The educational subvention amount calculated through the formula corresponds to the optimal educational network for a particular community, including the number and grades of schools. However, the networks are often “imperfect,” with only some schools meeting the Cabinet of Ministers’ parameters set in the formula (the actual number of classes often differs from the calculated one). Some communities have a school network that is too extensive, or their grades are not appropriate for the number of students (there are schools where only a few children study). In such cases, local councils are required to add funds from their budgets to pay for the teaching staff. Although local authorities have the right to decide how to spend their budget, we believe this is not the most rational use of limited resources because small schools have lower education quality at a significantly higher cost per student. Some communities have optimized their school network and receive more educational subventions than necessary to pay their teachers’ salaries in full. In such cases, the community can offer additional incentives and bonuses to teachers. Furthermore, any unspent funds from the remainder of the educational subvention can be used for schools’ material and technical modernization.

What has changed in recent years?

The government has frequently altered the educational subvention formula, including in 2021, which was the first year of operation for the vast majority of territorial communities. One notable change was the introduction of “buffers,” whose size and necessity were dependent on the actual class occupancy compared to the estimated capacity. If a community exceeded the estimated level, it would face a shortage of funds for teachers’ salaries. These “buffers” allowed the community to receive additional subvention in such cases. However, this came at the expense of communities that had already optimized their school networks and therefore had a higher actual number of students in a class than the calculated capacity. Essentially, it was a “leveling” of community educational networks.

On the one hand, this approach was unfair because the communities with the political will to optimize their network (i.e., shut down schools or reduce the number of classes) did not receive the surplus funds they were expecting. On the other hand, unoptimized networks inherited by new communities from former districts (which were not interested in doing anything) could drain their budgets. While the “buffers” allowed some communities to pass 2021 without significant stress, those with earlier-formed communities that experienced a reduction in subvention felt aggrieved.

The year 2022 saw the removal of the “buffers” and introduction of a revised matrix for estimating class occupancy (ECO). The adjustment factor for other teaching staff was increased based on the rural population share in the community, the annual salary of teachers underwent a change, and the salary fund for inclusion assistants was divided into the salary fund for pedagogues of inclusive resource centers (IRC) and the salary fund for inclusion assistants. This led to an increase in the salary of pedagogues.

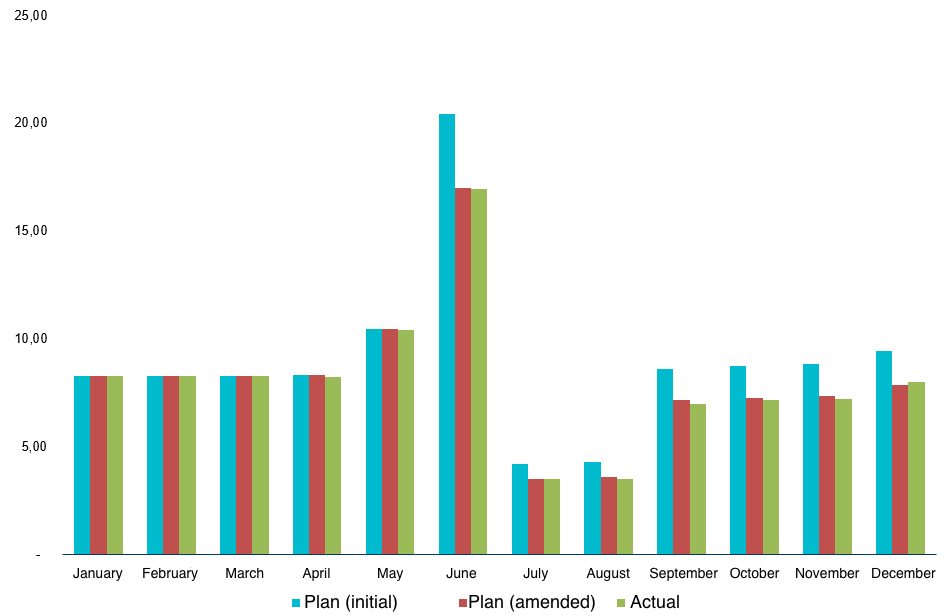

Then the war broke out. The Verkhovna Rada amended the state budget in the initial weeks of the full-scale invasion. These amendments included an increase in funding for the reserve fund while reducing allocations for other budget programs. One of the programs affected was the subvention to local budgets, with a reduction of UAH 17 billion. The educational subvention, which is traditionally the largest in terms of volume, was also reduced by UAH 10.8 billion, representing a 10% cut. This reduction, coupled with a decrease in income in the following months, led to a reduction in funding for teachers’ wages from June to December by an average of 17% per month, which prompted the Ministry of Education and Science to suggest that local councils should consider reducing allowances and additional payments to teachers, where possible.

Figure 1. The dynamics of the decrease in the amount of educational subvention in 2022, UAH billion

Source: OpenBudget portal, calculations of the Center

What about this year?

In late 2022, the Ministry of Education and Science disclosed information regarding the allotment of funds to communities for 2023. This was done in the midst of a full-blown war and mass migration of both students and teachers. According to data from the Ministry of Education and Science, the number of students attending general secondary education institutions decreased by 5% compared to September 2021. Additionally, the total funds allocated for educational subvention from the state budget were reduced by 20% compared to the 2022 year’s budget. This reduction resulted in the distribution of subvention funds being delayed until December 30, which substantially complicated the process of local budget planning. The delay was also caused by the need to identify students who had migrated and were attending multiple schools simultaneously (both at their actual residence and at their native school through remote learning). For the first time, the Ministry of Education and Science collected personal data from students attending general secondary education institutions, similar to the personal data collection from teachers introduced a year earlier.

The Ministry of Education and Science decided to keep the same formula for the distribution of the educational subvention that had been used between 2018 and 2022 but made two significant changes that would only take effect in 2023:

- Additional hours for certain subjects, optional courses, and individual classes will no longer receive state funding, which means a reduction in the curricula used for distributing educational subventions;

- A 0.9 factor will be applied to adjust the subvention amount, calculated according to last year’s formula for distributing the educational subvention.

The Ministry of Education and Science intends to review the required amounts and propose modifications to the distribution of funds during 2023, considering the current active population migration and the anticipated liberation of territories.

A significant change introduced this year was the government’s decision to withdraw any remaining educational subventions from previous years and transfer them to the state budget. As of October 1, 2022, State Treasury records showed that over UAH 8.7 billion of such funds were still in the accounts of local budgets, although this amount decreased by the end of the year as communities rushed to spend it. This decision was somewhat controversial. On the one hand, having such a large amount of funds simply sitting idle in treasury accounts during wartime could be seen as wasteful. On the other hand, the “rules of the game” had been established earlier, and some communities had made unpopular decisions under them. Taking away their “reward” now could potentially reduce trust in the central government. In our view, the government should clearly communicate the conditions under which these “saved” funds will be returned to communities, taking into account the changed demographic situation in those communities.

What does this mean for the communities?

Based on our analysis, a considerable number (over 50%) of communities will face a shortfall in funding to cover teacher wages this year due to the reduced subvention. This situation will compel local authorities to make tough decisions such as:

- restructuring the educational network by closing or downgrading certain schools;

- increasing co-financing from their own local budget revenues;

- exploring cost-saving options.

Since the summer of 2021, the first option has been unfeasible until a prompt solution is found. As per Article 32 of the Law of Ukraine, “On Complete General Secondary Education,” local councils are required to hold public discussions of the councils’ draft decisions one year before the commencement of optimization. Nonetheless, this option only “treats the disease, not the symptoms.” Eventually, it will have to be revisited.

The second option is most frequently employed, with local governments being forced to prioritize “keeping small schools afloat” if the community’s residents believe their taxes should be allocated in this manner. As a result, less funding is available for development projects.

The third option is savings. Some communities do find opportunities to save. What do they do about this? Staff lists are checked so that there are no teachers on 0.25 rates (since the USC cannot be lower than 22% of the minimum salary, the USC of four rates is 0.25 higher than the USC of one whole rate), and the allowance for prestige is reduced (the framework is defined by law, so those who have money take its upper limit, those who do not have the lower limit), as well as some other “optional” payments are not paid (office management, lesson substitutions, group work, extended day groups, etc.). The use of this tool should be very well thought out. On the one hand, there is a rational grain here (e.g., if the school has switched to distance education, classroom management and an extended day group probably do not occur). Still, on the other hand, the quality of the educational process should not be allowed to deteriorate (e.g., it is necessary to preserve the division into groups where it is needed and support the work of quality circles, and it is also vital to maintaining the personnel potential of educators.)

Cedos and SaveEd conducted research that indicates the educational process in the 2022/2023 academic year began in 12,996 schools, which is 1,000 fewer than the previous academic year. The form of education in these schools varied, depending on the security situation in the region and the availability of shelter. As per the Ministry of Education, at the end of 2022, education was being conducted remotely in 36% of schools, in a mixed form in another 36%, and full-time in 28% of schools, with most of the schools unable to teach children in the usual way situated in the eastern and southern regions. Communities are building and repairing shelters in schools and purchasing school buses to restore the classroom training format. These expenses are covered by the state and local budgets, along with support from international partners and donors. As of January 12, 2023, the total provision of shelters in schools is 71% (housing 62% of people), including both shelters in the schools’ own civil defense facilities (12%) and the simplest school shelters.

Why the quality of education?

Shutting down schools is not a well-liked decision, as many villagers believe that without a school, there will be no village. Nevertheless, the educational subvention formula criteria encourage communities to optimize their educational systems. Although in some communities, an inadequate network may be reasonable in the government’s opinion (e.g., in mountainous regions or areas with poor transport infrastructure) to avoid depriving children of education. However, in most communities with a suboptimal network, the issue is due to pandering to the local government electorate.

Looking beyond the surface, optimizing schools is not just a matter of finances but rather a crucial factor in determining the quality of education. Despite claims by directors and owners of small schools that they offer an “individual” approach to each child, research and the results of external evaluations suggest otherwise. We believe that closing a small, inefficient school in a village is not an act against education but rather a step towards ensuring access to quality education for children. Leaving such schools untouched is, in fact, a disservice to the children who “study” there, as it deprives them of their right to receive a quality education. Access to quality education should be a priority, so financial and other incentives should encourage communities to organize the transportation of children to support schools and not keep small schools “afloat.”

At the onset of the full-scale invasion, a considerable number of school buses were repurposed by communities to support the Armed Forces. As per the Minister of Education, around 500 units were destroyed or damaged due to the shelling by the Russian aggressor, and over 1.6 thousand school buses were allocated for evacuating civilians from active combat zones. Consequently, the issue of transportation has resurfaced and necessitates additional funding. In certain regions, last year’s remaining educational subvention was utilized to purchase new buses, despite limitations imposed by the war (e.g., the Lviv Region procured 126 buses via co-financing from the state budget, regional budget, and territorial community funds). Moreover, the 2023 state budget has allocated UAH 1 billion as a separate subvention from the state budget to local budgets for purchasing school buses.

Conclusions

We believe that education must be a top priority for reforms. Education is the key to our future, and without a proper education system in place, our country will face significant challenges. It is crucial that all stakeholders recognize that ensuring access to quality education is the ultimate goal guiding both funding allocation and educational network formation.

How can the situation in education be improved?

- The Ministry of Education and Science, in collaboration with local authorities, should adopt the “money follows the child” principle by establishing a system for quickly collecting information on student enrollment, as the number of students in certain settlements will change rapidly during and after the war (due to people leaving and returning, and the need for reconstruction in previously occupied territories);

- During the war, a certain reserve of educational subvention should be established to account for unforeseen circumstances (this could involve modifying the formula for distributing the subvention as outlined in Article 103-2 of the BCU). Additionally, funds should be allocated to finance the salaries of mobilized workers, which are currently not covered by the educational subvention despite being mandated by legislation;

- Transparency and clear communication are essential for the Ministry of Education to implement its policy effectively (it is necessary to provide precise information to communities about the number of teachers that can be financed with subvention funds). The benefits of consolidating schools should also be explained to parents to gain their support for the reform. The Ministry of Education should provide advisory support and be actively involved in planning school networks and lobbying for funds to transport students along new routes. This includes purchasing school buses and repairing relevant roads;

- The working group responsible for education at the Ministry of Education and Science should explore the feasibility of including qualitative measures, such as external exam results, into the subvention formula as a means of incentivizing communities (education management bodies);

- To prevent a negative impact on the progress of education reform, the government and deputies should avoid reducing spending on education. Instead, they should collaborate more actively with international organizations that can offer essential support. It’s worth noting that this year there are no “educational” subventions primarily aimed at educational capital expenditures. This absence of funding could hinder the advancement of the new Ukrainian school and other reform efforts;

- Once martial law ends, the remaining funds from the educational subvention that were returned to the state budget should be reallocated to the communities they were intended for. This will help restore the state’s reputation as a dependable partner of local governments that follows established regulations;

- The idea of incentivizing young teachers to work in schools should be revisited, and support should be provided for the professional development of teachers. This support should not be limited to bureaucratic attestations but should focus on providing actual knowledge and skills. The Ministry of Education and Science and regional education departments should work towards improving existing programs in the Centers for the Professional Development of Pedagogical Workers. Additionally, accreditation for independent courses should be simplified to encourage more teachers to take part;

- It is essential to encourage local authorities to invest resources in education development within their communities. The Ministry of Education and Science and/or the relevant VRU committee can achieve this by developing new co-financing programs from the state and local budgets. These programs should include measures to improve the material and technical base of schools, teacher internships in other schools, and exchange programs, among other things.

Attention

Автор не є співробітником, не консультує, не володіє акціями та не отримує фінансування від жодної компанії чи організації, яка б мала користь від цієї статті, а також жодним чином з ними не пов’язаний