19 thousand sanctions were applied to Russia, but some areas remain untouched. For example, it is unacceptable to offend the “great Russian culture” or to restrict Russian science because academic freedom is considered a sacred foundation of the scientific community.

Russia actively takes advantage of this attitude, spreading propaganda through scientific publications. Despite this, international journals, publishers, and research databases continue to collaborate with Russian journals and institutions, even with those who openly support the war and annexation of Ukrainian territories. Unfortunately, Ukraine sometimes facilitates such cooperation, for example, by registering Russian journals, and some Ukrainian scientists publishing in Russian journals alongside Russian colleagues.

The Ministry of Education and Science (MES) is trying to counteract this, but its resources are limited. In this article, we highlight the scale of the problem and call those scientists who care to join efforts in addressing it.

Should Russian science be sanctioned?

Although Russia is subject to three times more sanctions than Iran and five times more sanctions than Syria or North Korea, Russian science does not feel like an outcast on the international stage. Leading international publishers (Springer Nature, Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, Brill, etc.) continue to publish Russian journals and books, while international research databases like Scopus and Web of Science index Russian journals and articles, even those produced by institutions that actively support the war against Ukraine.

The following arguments are made in discussions on scientific collaboration with Russians: science should remain apolitical, academic freedom should be untouched, and sanctions could disrupt the free exchange of ideas and complicate certain important research, such as climate change studies. However, there are also plenty of arguments in favor of imposing sanctions (Table 1), and we explore some of them in more detail below.

Table 1. Key arguments pro and con academic sanctions on Russian scientists

| pro sanctions | con sanctions |

|

|

Source: compiled by the authors

Russian scientists are not “beyond politics”

Among the lasting debate on whether to impose sanctions on Russian scientists, Russian science is actively engaged in propaganda and supporting aggression against Ukraine. For example, in 2022, the Russian Union of Rectors, representing over 700 university rectors and presidents, issued a statement (the so-called “Rectors’ Letter”) in support of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) Presidium also endorsed the invasion, and the Lebedev Physical Institute of RAS issued a letter backing the war, signed by about 300 academics. Similar statements and letters were published by the Academic Council of Lomonosov Moscow State University, 1,100 scientists from Saint Petersburg State University, employees of the National Research Center “Kurchatov Institute,” many Russian professors, etc.

Moreover, Russian academic organizations provide material support to the aggressor’s army, directly assist in the annexation of Ukrainian territories, spread propaganda, conduct military-oriented research, fund scientific projects, and educate Russian soldiers and youth in the annexed territories.

For instance, RAS academics raised 32 million rubles ($3.5 million) for Russians fighting in Ukraine. Employees of the RAS Ufa Institute of Chemistry, together with the NGO “Reliable Rear of Bashkortostan”, organized a volunteer movement in support of the occupiers. Viktor Sadovnichiy, Rector of Moscow State University and President of the Russian Union of Rectors, oversees the “integration” of universities from the occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions into the Russian educational system, recruiting students and children of Russian soldiers as students. The Russian Science Foundation funds projects in the occupied territories. The propaganda efforts of Russian scientific and educational institutions range from lectures by Russian occupiers and pseudo-historians to writing textbooks that justify the war. Russian science directly aids the military by developing body armor, missiles, drones, and more while also preparing specialists for military production.

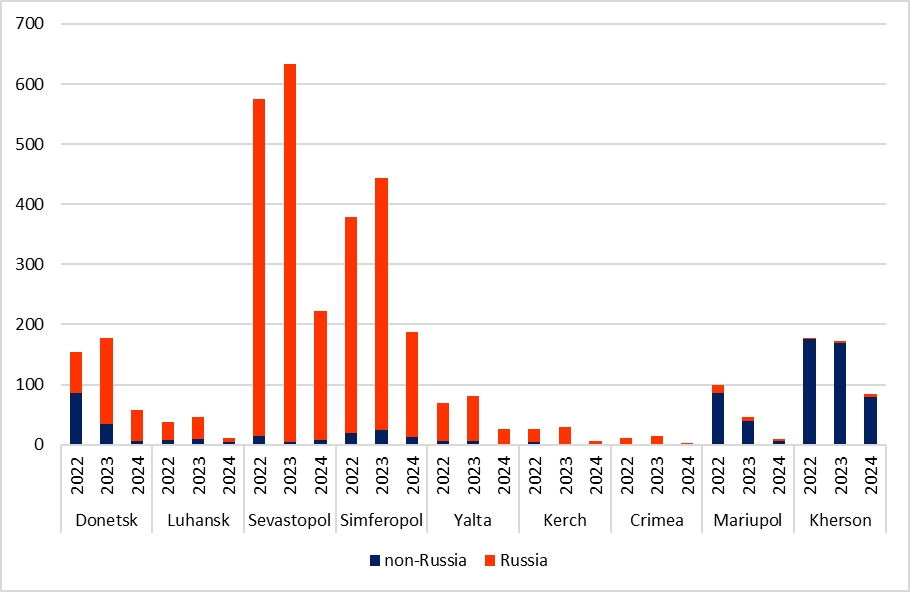

And, of course, Russian scientific community, in line with the Russian government, labels occupied territories as Russian in authors’ affiliations and in the biographies of editorial board members of journals. Figure 1 shows that in almost all articles by authors affiliated with institutions located in occupied territories, these territories are labeled as Russian (i.e., if an author is from Donetsk, they are labeled “Donetsk, Russia”). As evident from Figure 1, Russian scientists even managed to “claim” Kherson as a part of Russia despite it being under occupation for a relatively short time.

It is crucial to inform the international community that in the occupied territories, Russia has established fake institutions using the facilities and property of universities that were evacuated to government-controlled areas of Ukraine. These counterfeit institutions often have similar or identical names. For example, the occupiers turned the Vasyl Stus Donetsk National University into Donetsk State University and renamed the Marine Hydrophysical Institute of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in Sevastopol to the Marine Hydrophysical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Thus, Russia deceives the international scientific community.

Figure 1. Ukrainian territories labeled as Russian (in red) in articles published in Scopus (Elsevier)

Note. Data was collected by the authors using Scopus database with search filters for “Russian Federation” and cities/regions (Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, etc.). Randomly selected cases were then manually verified. Data for this graph are provided in Table A1 in the Annex.

Additionally, “scientific” articles may contain direct propaganda — for instance, justifying Russia’s “historical” claims to Ukrainian lands or referring to the “DPR/LPR” as independent states. There are hundreds of such works published in peer-reviewed(!) journals. Some examples are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Russian propaganda in scientific articles: selected examples indexed in Scopus or published by international publishers

| Journal (Publisher) | Example of Propaganda |

| Russian Social Science Review (Taylor and Francis) | Justification of the legality of Crimea’s annexation (Article by Russian propagandist M. Delyagin) |

| Eurasian Geography and Economics (Taylor and Francis) | Justification of Crimea’s annexation by American professors |

| Public Health and Life Environment (Federal Center for Hygiene and Epidemiology of Russia) | Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson Regions are referred to and discussed as parts of the Russian Federation (article by Russian scientists on the spread of cholera in these regions) |

| Almanac of Clinical Medicine (Vladimirsky Moscow Regional Research and Clinical Institute) | Donetsk is referred to as part of the Russian Federation (article on cancer by scientists from the “Donetsk Medical Institute of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation”) |

| Kutafin Law Review (Kutafin Moscow State Law University) | Justification of the so-called DPR and LPR (article on the necessity to recognize educational documents from the “republics”) |

| Psychology and Law (Moscow State University of Psychology and Education) | Instead of the Donetsk Region of Ukraine, the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic is referred to as part of Russia (article discusses the well-being of adolescents in the conflict zone) |

| RUSI Journal (Taylor and Francis) | Propaganda of Crimea’s annexation (article explains the central role of Crimea in the Russian “historical” myth) |

Despite this, international scientific publishers continue to collaborate with Russian universities and research institutes, including those that supported the war and even those sanctioned.

Springer publishes up to 200 Russian journals, around 80 of which are founded or owned by the RAS, and thus spread propaganda (see examples in Table A2 in the Annex). Among them is “Applied Magnetic Resonance,” published by the RAS Kazan Scientific Center, sanctioned by the US. Springer also publishes journals from universities whose rectors signed the aforementioned “Rectors’ Letter” (examples in Table A3 of the appendix), as well as a journal of “Rosatom,” the corporation that controls the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant and threatens the world with a nuclear disaster.

The publishing house Taylor & Francis, in its journal “Welding International,” publishes articles from the Russian journal “Welding Production.” The latter is published by LLC “Publishing Center ‘Machinery Technology,'” whose president, Valentin Kazakov, is a full member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. On the journal’s website, he explains that welding technologies help develop Russia’s military industry. Additionally, the recently published yearbook “Territories of the Russian Federation” includes surveys covering the annexed Crimea and Sevastopol.

The Scopus database (owned by Elsevier) indexes over 800 Russian journals, 77 of which were added to the index during 2022-2023. Of these, 19 are founded by universities whose rectors signed a letter in support of the war, and at least 20 are published by or indirectly associated with the Russian Academy of Sciences (e.g., representatives of the Academy are on the editorial boards of these publications, as shown in Table A4 of the appendix). Similar issues exist with the World of Science database by Clarivate, which indexes about 500 Russian journals.

Why do international publishers publish Russian journals?

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a number of leading academic publishers (Elsevier, Springer Nature, Cambridge University Press, IOP Publishing, Brill, and many others) signed a public statement against the war. Specifically, the statement said:

“We have taken the unprecedented step of suspending sales and marketing of products and services to research organizations in Russia and Belarus… Our actions are not targeted at Russian researchers, but rather at research organizations in Russia and Belarus.”

In addition, many international organizations (Springer Nature, Elsevier, Clarivate, Brill, and others) issued individual statements condemning the invasion and expressing full support for Ukraine.

However, these publishers continue disseminating Russian propaganda by publishing journals whose editorial board members work in “Simferopol, Russia“ or “Russian“ Sevastopol (these are occupied territories of Ukraine).

We asked several major academic publishers — Elsevier, Springer, Brill, Taylor & Francis, and Clarivate — about this issue. Their responses ranged from publishers not altering affiliations provided by authors, to compliance with the official sanctions regime (i.e., they collaborate with non-sanctioned organizations), and to them believing that sanctions should target institutions rather than individual researchers. Specifically, Elsevier noted that it does not change data in its sources. If it independently assigns a country code to publications, it follows the ISO 3166 standard (a coding standard for countries and territories based on internationally recognized borders).

Thus, Elsevier, as well as other publishers, has chosen the easiest way by leaving responsibility with the authors. Meanwhile, adherence to international law would require them to establish a clear affiliation policy and to penalize authors for violating this policy. They should also review and correct already published articles in accordance with the ISO 3166 standard.

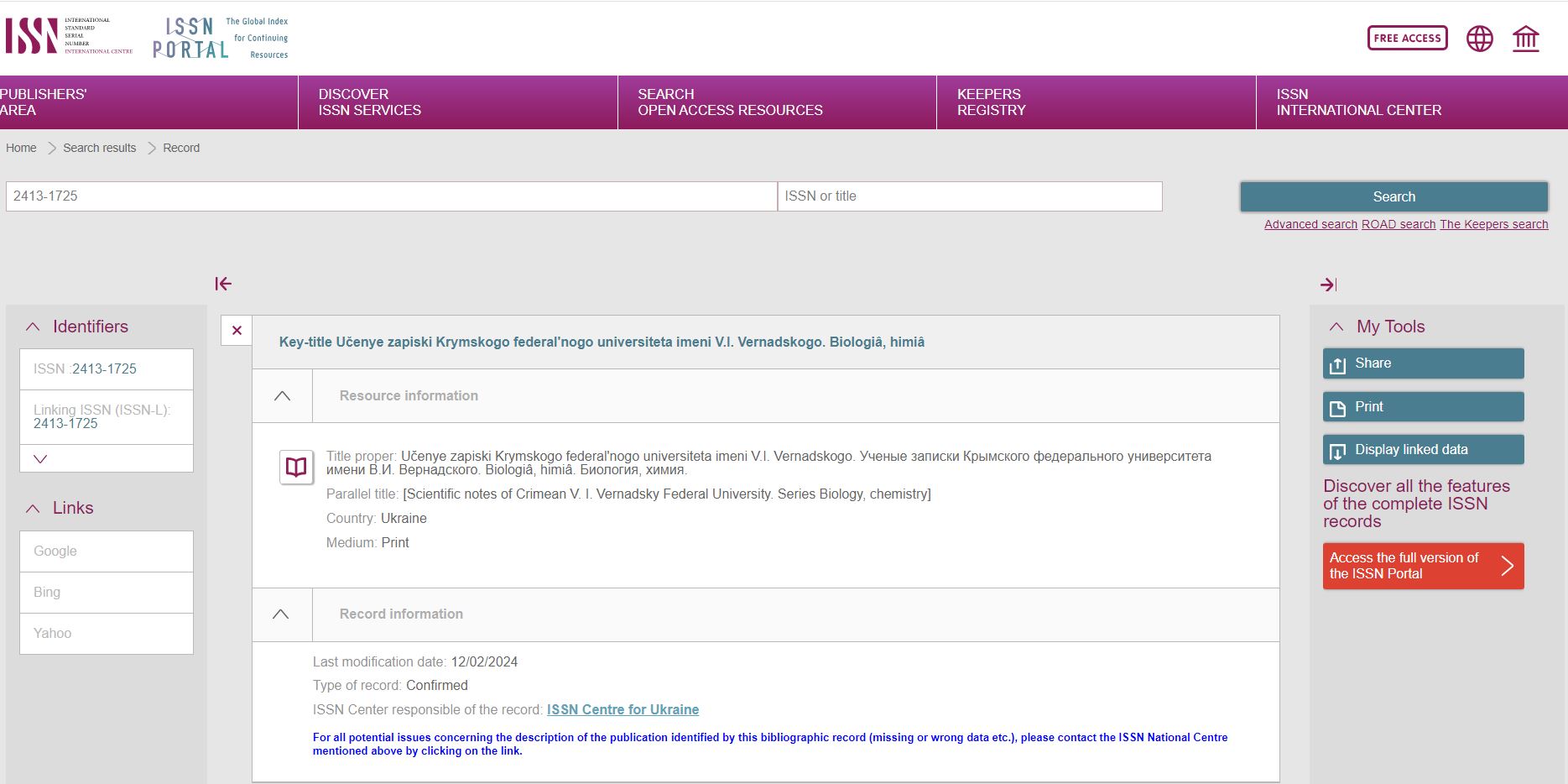

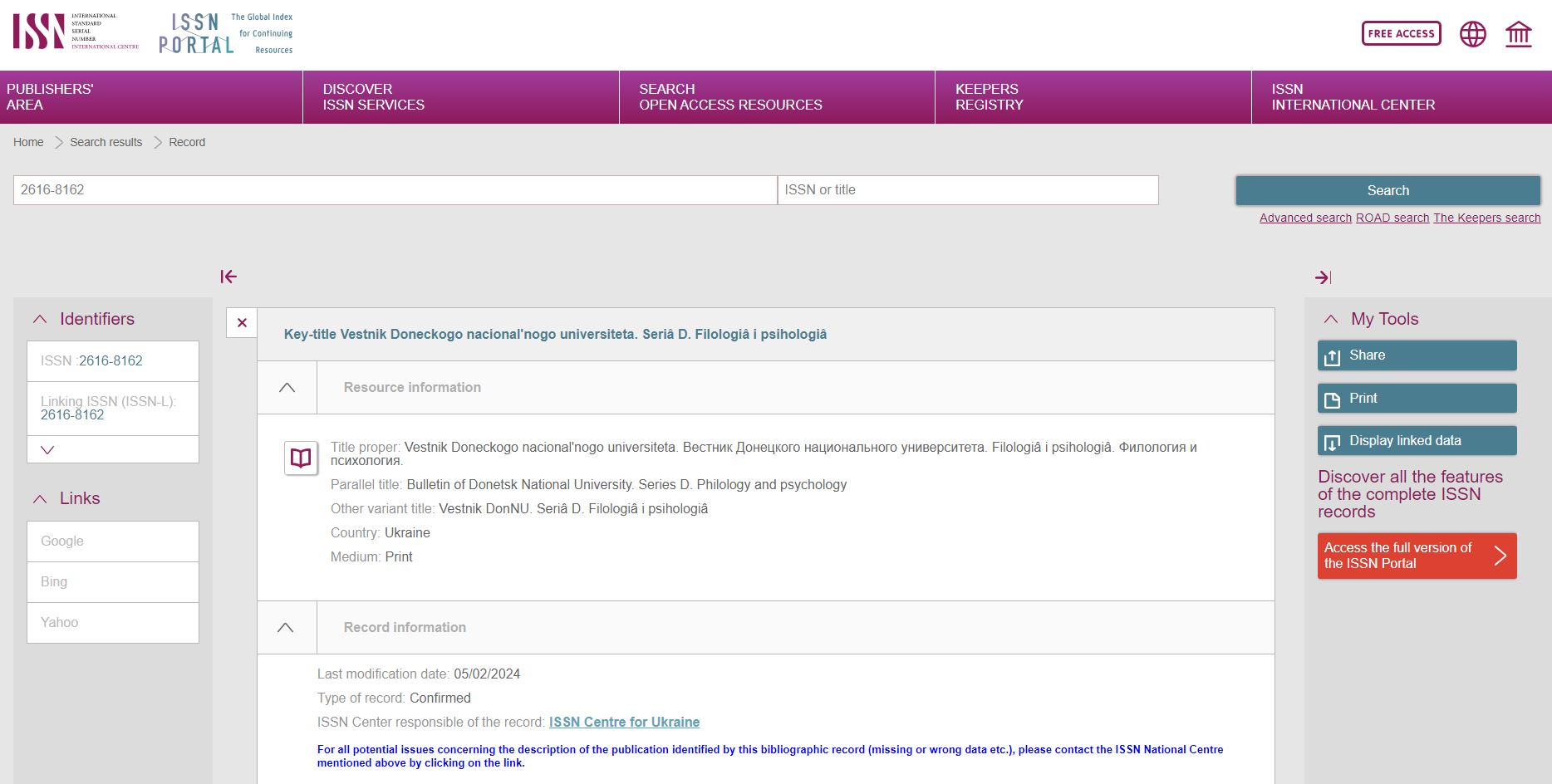

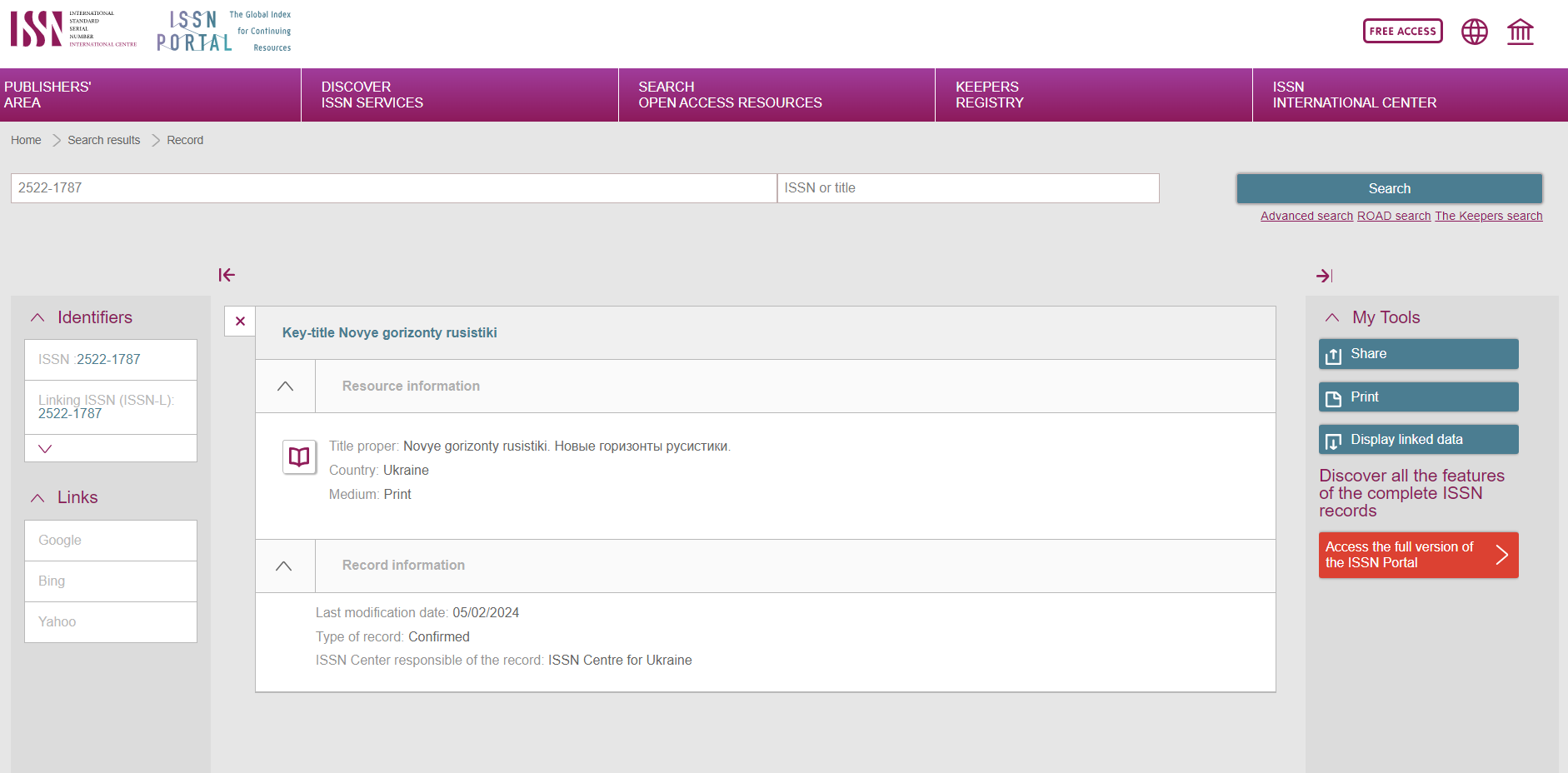

However, even worse is that not only do Western publishers collaborate with Russian scientists, but the National ISSN Center in Ukraine does this too by maintaining records in the ISSN database for Russian scientific journals and periodicals from annexed territories. This action (or inaction) lasts at least since 2021. Although the Ukrainian ISSN center denies assigning codes to journals from the occupied territories, the ISSN database contains at least 50 such publications with the status “Approved by the Ukrainian ISSN center in 2024” (examples are in the appendix). Thus, it turns out that even the international ISSN organization does not comply with the ISO 3166 standard, registering Russian journals published in occupied territories.

Note: ISSN is an international code assigned to periodicals (newspapers, journals, yearbooks, etc.). It is a unique identifier that allows distinguishing even publications with the same titles. Today, 90 countries participate in this system. ISSN codes are assigned by the International ISSN Center or by national centers. In Ukraine since 2019, this center has been the Ivan Fedorov Book Chamber.

“Dead Soul” reviewers: foreigners and Ukrainians on the editorial boards of Russian journals

For an article to be published in a scientific journal, it must be reviewed by several experts in the field. This review process is necessary to filter out low-quality work. Therefore, we decided to examine who reviews the work of Russian authors and grants them the status of a peer-reviewed publication. From 300 Russian journals published by international publishers or added to the Scopus database in 2022-2023, we selected 140 journals with two or more foreign editorial board members. We then created a database of foreign editorial boards members of these journals, totaling 709 individuals. We wrote to each of them, providing examples of Russian propaganda in scientific articles, and asked whether they planned to resign from the editorial board (the geographical distribution of the letters is shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Geography of letters sent to foreign editorial board members of Russian journals

Note. The map shows 733 letters sent. There are more letters than scholars because some individuals simultaneously serve on the editorial boards of several journals.

We found that eight of these individuals had already passed away, and nine had retired, i.e. they no longer have academic jobs. Of the remaining 148 from whom we received responses as of August 20, 2024, 45 learned from us that they were editorial board members, and 100 were listed there only formally, i.e. they did not perform any reviewer duties. At the same time, 89 scholars replied that they planned to resign from the editorial boards or had already written to Elsevier requesting their resignation, 22 said they would continue their collaboration, and five did not express any position on the issue.

Of the 709 international editorial board members of Russian journals whom we identified, 30 were Ukrainians. Of these, three had already passed away, and two had retired. From the remaining group, we received 15 responses. Of these, two learned about their involvement in the editorial board from us, and nine wrote requests to be removed from the board after receiving our letters. The rest had resigned earlier and disconnected from the journals.

Thus, Russian journals are misleading their readers about the composition of their editorial boards, thereby violating principles of academic integrity, which automatically places them outside the realm of academic protection.

What is the Ministry doing?

Formally, the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (MES) is responsible for the academic environment in the country and should be countering propaganda by Russian science. However, in reality, MES lacks the resources (human, financial, material, etc.) to effectively counter this, especially on the international level. Domestically, MES prohibits cooperation between Ukrainian scholars and organizations with Russian counterparts and prevents public funding of projects involving any form of collaboration with the aggressor state (e.g., joint publications with Russian scientists or in Russian journals).

Given the limited resources of MES, one of the few effective forms of resistance against the aggressor is collaboration with activists. For instance, in response to activist appeals, MES initiated the cessation of indexing Russian journals from temporarily occupied territories in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) and began investigating the legality of the Ukrainian ISSN center's actions regarding the assignment of ISSN numbers to journals published by institutions appropriated by Russia in these territories. MES is establishing a working group to unite Ukrainian activists for targeted actions aimed at limiting cooperation between Russian scientists and international publishers.

What can we do?

Correspondence with leading international publishers and research databases revealed that the basis for continuing collaboration with Russian academic organizations, journals, etc. is the absence of formal sanctions. Publishers like Springer Nature or Elsevier are open to reviewing their cooperation with Russians if the European Commission or the US government (OFAC) bans such collaboration and/or imposes sanctions on Russian educational and scientific institutions (particularly those located in occupied territories), as well as on individual scientists who support the war and engage in propaganda. In the absence of such bans and sanctions, these publishers technically do not violate any rules.

We believe the situation can be changed through public discussion of this topic, particularly within academic and political circles. Such a discussion should prompt actions from the executive authorities and increase the reputational risks for international organizations (publishers, research databases, etc.) that cooperate with Russians. How can we increase these risks? A first step could be to send inquiries to relevant publishers asking why they are supporting Russian propaganda. For instance, in response to our inquiry, Elsevier promised to cease publishing Russian journals since 2025. However, systemic changes require sustained efforts by both the Ukrainian government and the academic community, supported by international colleagues.

Annex

Table A1: Ukrainian Territories Labeled as Russian in Articles Published on Scopus (Elsevier)

| Ukraine's territories | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Donetsk | 154 | 177 | 58 |

| Donetsk labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 68 | 142 | 51 |

| Luhansk | 38 | 46 | 12 |

| Luhansk labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 30 | 37 | 8 |

| Sevastopol | 575 | 633 | 223 |

| Sevastopol labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 560 | 628 | 215 |

| Simferopol | 379 | 444 | 187 |

| Simferopol labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 360 | 420 | 174 |

| Yalta | 69 | 81 | 26 |

| Yalta labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 62 | 75 | 24 |

| Kerch | 27 | 29 | 7 |

| Kerch labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 22 | 29 | 7 |

| Crimea | 11 | 15 | 3 |

| Crimea labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 11 | 13 | 2 |

| Mariupol | 100 | 46 | 10 |

| Mariupol labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 14 | 7 | 3 |

| Kherson | 178 | 173 | 84 |

| Kherson labeled as a territory of the Russian Federation | 2 | 4 | 5 |

Note: The table refers to articles in which the authors' affiliations list Ukrainian territories as Russian. The numbers in the table indicate the number of such articles.

Table A2: Examples of RAS Journals Published by Springer

| # | Springer Journal | Russian Equivalent and Publisher |

| 1 | “Applied Magnetic Resonance“ | “Applied Magnetic Resonance“ (RAS Zavoisky Physical-Technical Institute) |

| 2 | “Astronomy Reports“ | “Астрономический журнал“ (RAS Institute of Astronomy) |

| 3 | “Astrophysical Bulletin“ | “Астрофизический бюллетень“ (RAS Special Astrophysical Observatory) |

| 4 | “Atmospheric and Oceanic Optics“ | “Оптика атмосферы и океана“ (RAS Institute of Atmospheric Optics, Siberian Branch) |

| 5 | “Automation and Remote Control“ | “Автоматика и телемеханика“ (Russian Academy of Sciences) |

| 6 | “Biochemistry (Moscow) “ | “Биохимия“ (Moscow State University) |

| 7 | “Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Physics” | Известия Российской академии наук. Серия физическая |

| 8 | “Cell and Tissue Biology“ | “Цитология“ (RAS Institute of Cytology) |

| 9 | “Colloid Journal“ | “Коллоидный журнал“ (Nauka Publishing House, RAS) |

| 10 | “Combustion, Explosion, and Shock Waves” | “Физика горения и взрыва“ (RAS, Siberian Branch) |

Table A3: Examples of Russian Journals Directly Linked to Universities Signatories of the “Rectors' Letter,” Published by Springer

| # | Springer Journal | Original Russian Journal, University Signatory of the Rectors' Letter |

| 1 | “Chemical and Petroleum Engineering” | “Химическое и нефтегазовое машиностроение,”

Moscow Polytechnic University |

| 2 | “Algebra and Logic“ | “Алгебра и логика,”

Novosibirsk State University |

| 3 | “Computational Mathematics and Modeling” | “Прикладная математика и информатика,”

Moscow State University |

| 4 | “Differential Equations“ | “Дифференциальные уравнения“

Moscow State University |

| 5 | “Lobachevskii Journal of Mathematics” | “Lobachevskii Journal of Mathematics”

Kazan State University |

| 6 | “Moscow University Biological Sciences Bulletin” | “Вестник Московского университета. Серия 16. Биология”

Moscow State University |

| 7 | “Moscow University Chemistry Bulletin” | “Вестник МГУ. Серия "Химия"'“

Moscow State University |

| 8 | “Moscow University Geology Bulletin” | “Вестник Московского университета. Серия 4. Геология“

Moscow State University |

| 9 | “Moscow University Soil Science Bulletin” | “Вестник Московского университета. Серия 17. Почвоведение”

Moscow State University |

| 10 | “Refractories and Industrial Ceramics” | “Новые огнеупоры“

National University of Science and Technology MISIS |

A4: Examples of Russian Journals Added to Scopus in 2022-2023

| Issued by universities whose rectors endorsed the war | Associated with the RAS |

| “Discrete and Continuous Models and Applied Computational Science” and “RUDN Journal of Medicine” (Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University of Russia) | “Russian Japanology Review” |

| “Historia Provinciae” (Cherepovets State University) | “The Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Studies in Literature and Language” |

| “Kutafin Law Review” (Kutafin Moscow State Law University) | “Theory and Practice of Meat Processing” |

| “Studia Religiosa Rossica” (Russian State University for the Humanities) | “Food systems” |

| “Vestnik Volgogradskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. Seriya 2. Yazykoznani” (Volgograd State University) | “Izvestiya RAN. Seriya literatury i yazyka” |

| “Vestnik Rossiyskikh Universitetov. Matematika” (Tambov State University) | “Literature of the Americas” |

| “Journal of Corporate Finance Research“ (National Research University “Higher School of Economics”) | “Russian Journal of Immunology” |

| “Obrabotka metallov-metal working and material science” (Novosibirsk State Technical University) | “Siberian Scientific Medical Journal” |

| “Sechenov Medical Journal” (Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University) | |

| “Siberian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine” (Tomsk State University) | |

| “Construction materials and products” (Belgorod State Technological University named after V.G. Shukhov) |

Examples of ISSN Assignment by the Ukrainian ISSN Center to Russian Journals Published in Occupied Territories

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations