“The increase of retirement age is unacceptable from the social and demographic points of view, since the average life expectancy for males in Ukraine is 66 years only.” – Lyashko claims.

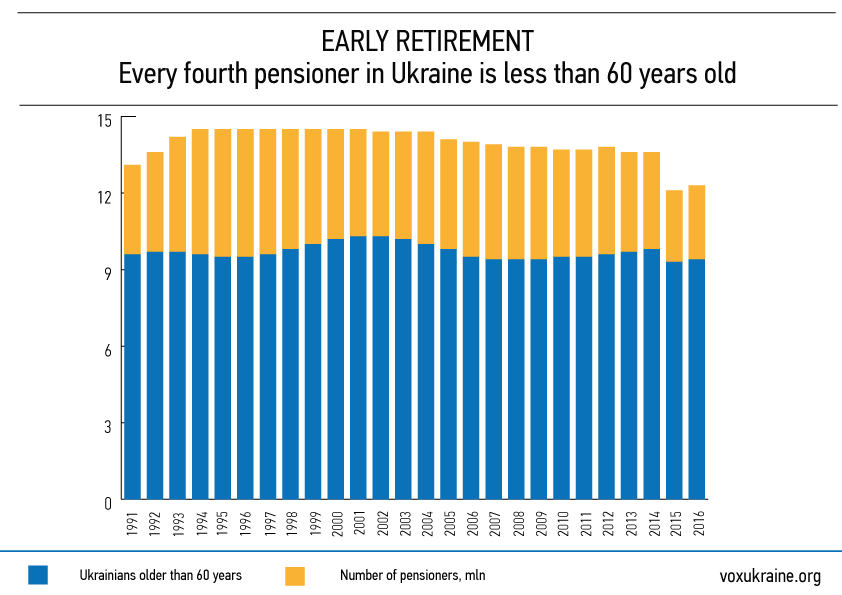

It’s true that the average life expectancy in Ukraine is lower than in most developed countries. However, what matters isn’t just the absolute retirement age, but also the average life expectancy at the time of retirement and early retirement. Ukrainian women hold one of the highest places in the world for life expectancy after retirement. In 2012, it was 23 years, hich, according to Ella Libanova, Director of the Institute for Demography and Social Studies, exceeds their average employment record. For men, the average life expectancy after of retirement is 14 years, which is comparable with the same figure for other countries. However, in Ukraine half f the male population retire at 60, and the rest — at 40. Thus, the average retirement age is 55 years. It’s one of the reasons why pension spending in Ukraine is among the world’s highest — 16% of GDP in 2013. In 2016, the Pension Fund deficit was 84,9 billion UAH, or approximately 4% of GDP. Meanwhile, the pensions remain small.

From the economic point of view, it’s important whether revenues and expenditures of the Pension Fund are balanced. Today, the Pension Fund income equals only half of its spending on pensions, and there are four solutions to cut the deficit (see here for the effect of these methods):

- Cut the number of those who receive pensions

- Raise the number of those who pay contributions to the Pension Fund, and their payment discipline

- Raise contributions from employees

- Widen the gap between salaries and pensions.

Increasing the retirement age and cancelling early retirement benefits gradually reduce the Pension Fund deficit thanks to the first two solutions. The increase in rates paid means increase of the tax burden and contradicts the policy of recent years, when this burden has been reduced, in particular, to promote shifting salaries out of the shadow economy. Widening the gap between salaries and pensions means increasing relative poverty. Of course, a normal state can’t be interested in that, not mentioning the fact that it can lead to social tensions.

So, none of the four solutions to balance the pension system is popular. However, increasing the retirement age (solutions 1 and 2) is a long-term solution to the problem (which will take a lot of time) compared with solutions (3) and (4), which will have a temporary effect and a negative impact on the economy and society.

Lyashko’s statements about the need “to focus on de-shadowing of the economy, particularly employment, fighting unemployment, and reducing emigration, developing domestic industry and entrepreneurship, improving demographics, and increasing incomes of the citizens” are correct.

But let’s face the reality. De-shadowing of the economy requires certain measures, and it’s unlikely to happen without restoring confidence in fiscal and human rights protection authorities, as well as the judiciary. Examples abound. The radical, almost two-fold reduction of the unified social tax to 22% in 2016 hasn’t bring tangible results in de-shadowing of the wages.

Reducing unemployment is an important issue, but it won’t be able to significantly improve the financial performance of the Pension Fund, since the unemployment rate in Ukraine is not too high. According to the State Statistics based on the methodology of the International Labour Organisation, the unemployment rate in Ukraine in January-September 2016 was 9,2% or the population aged 15-70. It isn’t much higher than the historic minimum recorded in 2007-2008 (6.,4%), which can be considered as the lower limit of a “natural level” under the current institutional conditions. Reduction of unemployment from 9% to 6.5% will reduce the deficit of the Pension Fund only by 3-4% — hence, it won’t solve the problem.

In recent years, the number of emigrants was around 15-20 thousand people a year, or about 0.1% of the workforce. Moreover, in recent years Ukraine has seen a positive migration balance, i.e. more people come here than leave it. The situation with temporary labour migrants (so-called gastarbeiters) is a separate issue — the number of employees abroad depends not only on employment problems within the country, but also with opportunities to earn elsewhere. Labour migration is typical not only to Ukraine, but also to other Eastern European countries (Poland, Hungary, and the Baltic states), where the average salary is several times higher than in Ukraine, and the economy is much more developed. Labour migration has both negative and positive sides — for example, it decreases unemployment and creates inflow of cash into the country.

Improving demographics, i.e. increasing birth rate and reducing death rate, is a very slow process, difficult to influence by the public policy. Moreover, the only currently used tool aimed at increasing the birth rate are payments for newborns provided regardless of income. About 50% of the social assistance budget, which could be aimed at the vulnerable groups of population, is spent on it. The experience of many countries shows that this tool isn’t effective for a real increase in the birth rate, but only shifts in time the decision to have a child to be able to receive the benefits.

The full article is available here

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations