Nearly 18 months after starting a war of naked aggression in Ukraine, the autocratic Russian President Vladimir Putin is learning that the financial price of an empire can be very high. Ukraine’s resolute defense has stymied a “modernized” Russian military that was supposed to steamroll the country in a few days and relegate Ukraine to a puppet state in Russia’s “near abroad.”

Currently, the Ukrainian counter-offensive grinds on, methodically liberating territory in the south and striking high-value targets in occupied Crimea. Facing comprehensive sanctions, the Russian government response has been to massively increase public expenditures to sustain demand. The unsustainability of this path should be clear, especially when one examines the long history of Russian adventurism and the impact it has had on the country’s finances.

Russia has long relied heavily on foreign investors to finance its territorial aggrandizement. In 1769, Tsarina Catherine II issued the first Russian sovereign bonds worth 500 thousand Dutch guilders in Amsterdam. Over the next 145 years, her successors issued thousands, then millions, then billions more in sovereign bonds, most often to finance wars of conquest and repression in the growing Russian Empire. No matter the outcome on battlefields and in financial markets abroad, Russian tsars always made their sovereign bond payments to foreign investors. By 1913, Tsar Nicholas II was making principal and interest payments on sovereign bonds worth a staggering $155 billion (8.873 billion 1913 rubles), with about half of those payments going to investors in the West, particularly France.

However, Russia’s seemingly insatiable need for territory and its reliance on others to finance it came at a steep cost when things went wrong. As a recently released paper of ours, seven years in the making, shows, Russia’s finances have always been harmed by its attempt to project power outside of its borders – or where it attempted to suppress rebellion in newly-acquired territories – precisely when the outcomes were not favorable to Russia. If lands were won, say after battling Ottoman Turkey, costs of Russian sovereign debt service went down, as new taxpayers were forcibly assimilated into the Empire. But if lands were lost, say after battling Imperial Japan, costs went up. The most disastrous military campaign of all, in World War I, brought economic collapse and political revolution in 1917, and then the Bolsheviks defaulted on Russia’s sovereign debt, executing Nicholas and his family in 1918.

Fast forward to today and Vladimir Putin’s ill-advised and unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. The cost of Russia’s invasion has been estimated at a total of US$167 billion as of September 16th, a staggering US$300 million per day, a number which is plausible given recent equipment losses in Crimea, and which does not begin to even incorporate the human cost. State finances were supposed to be the bright spot for Putin going into this military adventure, as Russian Central Bank gold and foreign currency reserves worth more than $360 billion were meant to assure convertibility of the ruble, as well as interest and principal payments on sovereign bonds trading abroad. But the Kremlin must have overlooked that most of those reserves were held by Western banks and governments, countries which have been surprisingly united in their willingness to freeze and seize these reserves. With the ruble worth approximately one US cent and massive capital flight over the past two years, the continued cost of waging a “special military operation” is showing in the government’s budgetary numbers. Russia already technically defaulted on its bonds in 2022 and its credit ratings were rated by S&P as “CC” after the invasion (meaning highly vulnerable).

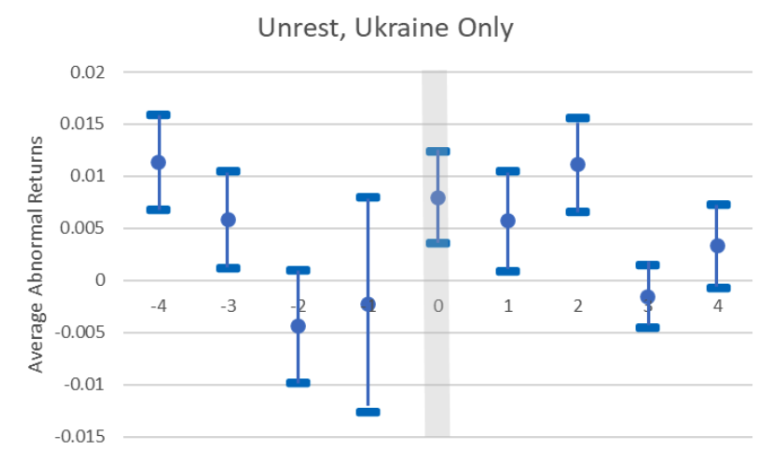

For students of history, this scenario should come as no surprise. Indeed, our paper shows that repeated bouts of collective violence in Ukraine in the 19th and early 20th centuries did the most damage to Russian finances, with 5-year Russian sovereign bond yields increasing by 5.1 basis points on average due to unrest in Ukraine (when compared against other violence in Russia’s periphery). When taken as a comparison against violence occurring in Russia itself, the magnitude is even larger, with an average effect of 6.7 basis points. The effect can clearly be seen in Russian bond yields as shown in the Figure below, where “abnormal” increases in bond yields spike in the month that an uprising occurs in Ukraine and remain elevated for at least two months afterwards.

Note: The top and bottom bars represent the 95% confidence interval for abnormal changes in bond yields, while the circle represents the estimated mean

Little more than a century ago, Russia’s military and financial woes swept away the previous Tsar. Long before that, however, Ukraine was causing problems for Russia’s finances simply by refusing to acquiesce to rule from Muscovy. While history rarely repeats itself exactly, in Russian in particular, it often rhymes. And the lessons of the 19th century appear to have been lost on Tsar Vladimir.

Christopher A. Hartwell is Professor of International Business Policy at ZHAW School of Management and Law in Zurich and Professor of International Management at Kozminski University in Poland. Paul M. Vaaler is Professor and John and Bruce Mooty Chair In Law & Business at the University of Minnesota’s Law School and Carlson School of Management. Their op-ed refers to research from their academic study entitled “The Price of Empire: Political Unrest Location and Sovereign Creditworthiness in Tsarist Russia.,” available on ArXiv.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations