The unthinkable is happening. Putin started an aggressive war against the people of Ukraine, a fellow Slav country in the middle of Europe. Babi Yar, a place where many thousands of people were shot by Hitler’s army to prove an insane racial theory, is where people are killed again by Putin’s army. Putin rattles nuclear weapons to scare the world. And yet money from Russian oil and gas exports are flowing to Putin’s coffers to pay for death and destruction.

History will judge harshly those who have enabled Putin’s regime. Gerhard Schröder will not be remembered as a chancellor of proud Germany. He will be remembered as somebody who corrupted Germany and contributed to the rise of Putin. The “reasons” for Nord Stream 2, a Germany-Russia gas pipeline bypassing Ukraine and thus lowering the cost of Russian invasion into Ukraine, look ludicrous in retrospect and it will stain everybody who was involved in it.

This is not the first moral error and it almost surely will not be the last.

It was morally wrong to buy anything from IG Farben that produced Cyclone B, a gas used to exterminate Jews in concentration camps. It was morally wrong to buy anything from the apartheid regime in South Africa. It was morally wrong to buy oil from Saddam Hussein who used chemical weapons to kill civilians.

But humanity makes progress by learning from mistakes. And the moral compass gives a clear bearing here: the civilized world must impose sanctions on Russian energy exports to raise the cost of war for Putin.

The economic calculus is clear too. Yes, energy prices will increase. They have increased already as private corporations shied away from Russian oil to avoid running afoul of potential sanctions. And while higher energy prices can seem inconvenient, they may not be that costly in the end. Indeed, the marvel of a market economy is that it always finds ways around scarce resources. Supply will increase. Energy will be used more efficiently, thus reducing pollution and emissions. Alternative energy sources will be pursued more intensively. Transportation networks will adjust. Reserves may be used to attenuate price increases. The global economy is much more resilient than many people think. For example, sanctions on Iran, a major oil producer, resulted in only short-lived increases in the price of oil.

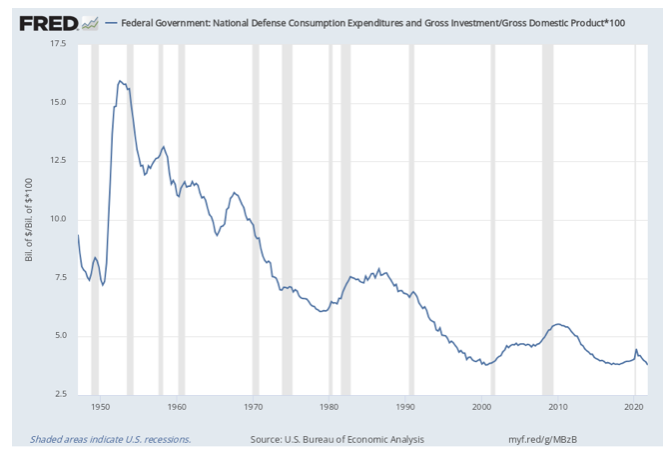

On the other hand, think about the cost of a new arms race that will be triggered if Putin succeeds in conquering Ukraine because no country will feel safe. This arms race has already begun as Germany (!) increased its military spending and committed to more increases in the future. And this will get worse. At the height of the Cold War, military spending in the U.S. accounted for almost 10 percent of the gross domestic product. This would correspond to 2 trillion dollars today. Think about it: 2 trillion dollars per year. In the U.S. alone. This is the money that could be spent on education, healthcare, infrastructure, etc. The “peace dividend” after the end of the Cold War allowed the world to have a new era of prosperity. This dividend should be protected.

Figure 1. Military spending as percent of Gross Domestic Product.

The balance is clear: sanctions on Russian energy will cripple the Russian economy, and they will carry a small price to pay for preserving the global security.

We can only ask ourselves now whether a credible promise to impose massive economic sanctions on Russia could have deterred Putin from the invasion. He certainly did not believe that whatever he was warned about was credible. But every day of the Russian war in Ukraine—with bombings of cities and shelling of a nuclear power plant—makes these questions come back, just like we ask ourselves decades later whether Hitler could have been stopped earlier. The free world can prevent unspeakable tragedies. Energy sanctions are a moral step in that direction.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations