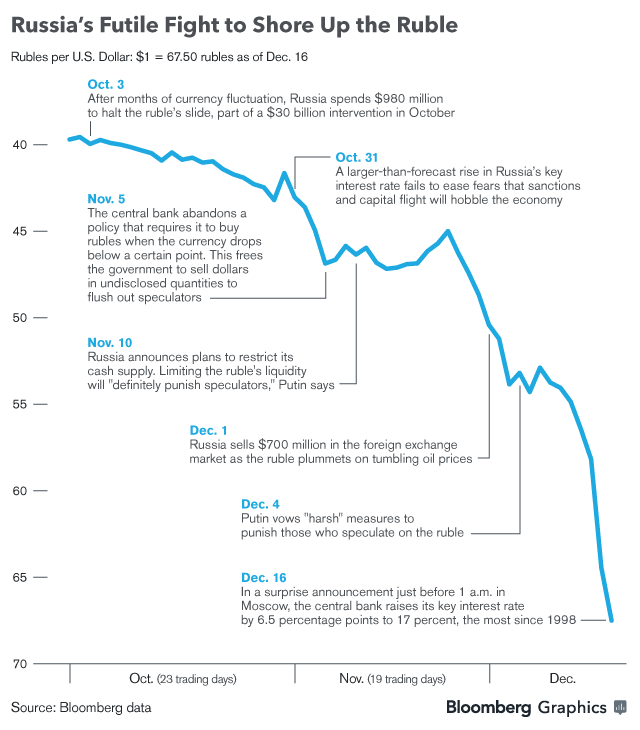

The ruble closed today at just under 70 to the dollar, down 13% after falling some 10% yesterday. At one point it fell below 80 to the dollar, down almost 20%.

It has now overtaken the hryvnia as the world’s worst performing currency this year.

The Russian Central Bank (RCB) has tried to fight the ruble’s fall by intervening in currency markets and raising interest rates. Yesterday, it increased interest rates a dramatic 650 basis points, from 10.5 to 17%, having already increased rates dramatically earlier in the year. Its foreign currency reserves, while still substantial, have also been falling, and with large corporate debt obligations dominated in dollars coming due next year, there is increasing talk of possible default by companies that partially or entirely state owned.

Net capital outflows are likely to come in at around $135 billion in 2014, twice as much as in 2013.

The RCB’s first deputy chairman, Sergei Shvetsov, told Interfax today that the situation might be as bad as the financial meltdown of 1998, which led to a Russian sovereign debt default. As he put it: “We could not imagine this in our worst nightmare a year ago.”

Inflation is now estimated to be 10% for the year and is accelerating rapidly thanks to the fall of the ruble. Russian equity prices, which had held up pretty well this year even in dollar terms, have fallen almost 10% this month and are now trading at an even bigger discount than they were a year ago. And ominously for Russia, Brent crude closed below $59 per barrel for the first time, a five year low.

Russia, in short, is experiencing a full-blown financial crisis, one that is certain to have a major impact on the country’s real economy going forward. Before the latest financial turmoil, most forecasters had the economy contracting 1-2% in 2015. Recently forecasters have been saying the recession was likely to be rather worse – perhaps a 2-3% decline in output in 2015.

The current run on the ruble, and the possibility that oil prices will stay low or may even fall farther, suggest that Russia’s recession will be deeper yet and last even longer. Yesterday the RCB announced that GDP could shrink 4.7 percent next year if Brent crude averages $60 per barrel or less.

The collapse of the ruble, and the recession, will also have important distributional effects inside Russia, in terms of both wealth and political power. Consumers will be hurt by higher prices and fewer Western goods on store shelves; businesses with significant dollar-denominated debt and no foreign currency revenue will be hurt by a huge jump in the real costs of debt servicing; businesses of all sizes that need to borrow will be hurt by high interest rates and lack of access to foreign capital as a result of sanctions; and individuals on fixed incomes, particularly pensioners, will be hurt. And for the first time since the 1990s, Russia may well start to experience serious unemployment problems, with all the attendant political consequences.

The big relative winner from this will be exporters, particularly those exporting commodities at prices that have held up better than oil prices on international oil markets. Exporters will benefit from foreign currency earnings that now buy a whole lot more at home than a year ago. For the most part, that means large companies, most of which are wholly or partially state-owned, will suffer less than small- and medium-sized enterprises, and in some cases they may actually be benefitting from the crisis.

Similarly, the fact that the federal government gets so much of its revenue, directly through taxes or indirectly from ownership, from commodity exports, and above all oil, means that the government is under less pressure than it would be otherwise.

Nonetheless, a dramatic decline in Russia’s terms of trade and falling GDP will mean that many of the federal government’s megaprojects – a fast train to Sochi, a bridge to Crimea, the 2016 World Cup, and so on – will have to be reconsidered. And military spending, at least eventually, is also likely to come under pressure, again despite very ambitious plans. There are simply too many projects with too little money to spend on them. The crisis will also raise more questions about the funding of, and the return on investment for, Moscow’s expensive energy infrastructure plans, notably pipelines to China and Turkey, drilling in the Arctic and remote Siberian fields, and fracking.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s economy is in even worse shape than Russia’s, thanks in part to a much lower starting point, the effects of war, and a collapse in trade with Russia. This week, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev warned in an op-ed in Nezavisimaya Gazeta that Moscow intends to increase economic pressure on Ukraine: “We will no longer support the Ukrainian economy. It is a burden for us and to be honest, we are tired of it.” Ukrainian officials, he continued, have “a poor understanding of the ultimate price they will have to pay” for rejecting Russia and turning to Europe.

The hryvnia has stabilized somewhat since mid-November, but it has fallen by roughly half this year against the dollar. Kyiv’s foreign currency reserves have shrunk to critical levels – below $10 billion – thanks to the central bank’s currency interventions, while inflation rose to 22% in November. Not surprisingly, given the real risk of a default on Ukraine’s sovereign debt, bond prices fell to record lows on December 10, with debt maturing in 2015 trading at a 25% discount.

To date, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has disbursed only $3 billion of the standby loan of $17 billion agreed to earlier in the year as it waits for signs that Kyiv’s new government is moving ahead with serious reforms. Meanwhile, an IMF delegation that arrived in Kyiv this week confirmed that even with reforms, the $17 billion current loan is going to fall well short of needs and that Ukraine will require an additional standby loan of $15 billion for 2015.

The importance of supporting Ukrainian efforts to reform and turn its economy around has been a constant theme for EU officials since the beginning of the crisis, but the EU has major economic and political problems of its own that will make supporting Ukraine more difficult. Its member-states, particularly those in the Eurozone, are still struggling economically even as Euroskepticism rises in most member-states, including the most important ones politically. As The Economist put it this week, “Even if the immediate threat of break-up has receded, the longer-term threat to the single currency has, if anything, increased. The euro zone seems to be trapped in a cycle of slow growth, high unemployment and dangerously low inflation.”

There is, I should add, at least some good news – the level of violence in the Donbas has diminished and there is at least some prospect that we will see a real separation of forces and stable ceasefire take effect.

Nonetheless, tensions between Russia and the West, above all on security matters, continue to escalate.

On Friday, Swedish officials announced that for a second time this year a Russian military jet that had turned off its transponder to avoid air traffic radar nearly collided with a SAS commercial airliner. Finnish authorities then announced over the weekend that their air traffic controllers had ordered another commercial airliner to change course last week to avoid a group of Russian military jets without their transponders on that were flying over the Baltic Sea.

And today, RT reported that the Russian military had carried out “a massive surprise drill in the Kaliningrad region to test the combat readiness of some 9,000 troops and 642 vehicles, including tactical Iskander-M ballistic missile systems rapidly deployed from the mainland.” The exercises come after Russian military officials asserted (correctly) earlier in the month that NATO was repositioning aviation near its borders that are “capable of delivering nuclear weapons to the Baltic nations.”

Meanwhile, in Washington the White House announced that President Obama would sign, albeit reluctantly, the Ukraine Freedom Support Act, which Congress sent to his desk last week. The law increases funding for military and other assistance to Ukraine next year. It also specifically authorizes the president to deliver lethal weapons to Ukraine, although the president has discretion as to whether to use that authority. The law also calls on the president to impose new economic sanctions on Russia, but again it gives him the option of waiving those sanctions if he feels not doing so is in the national interest.

While the legislation was thus watered down from earlier versions – for example, at the Administration’s urging, Congress has not afforded Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia the status of “Major Non-NATO Ally,” which would have made additional military assistance procedurally easier – it is nevertheless viewed in Moscow as highly provocative. Russian officials, with good reason, are also going to conclude that once Republicans take over the Senate, pressure on the White House to increase military assistance to Ukraine will likely grow.

Not surprisingly, Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, told France 24 in an interview today that there are “very serious reasons to believe” that Washington is intent on bringing about regime change in Moscow. And he added, “If you look at US Congress, 80 percent of them have never left the USA, so I’m not surprised about Russophobia in Congress.”

This is a re-post from Edward Walker’s blog.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations