The Kremlin media’s well-known narrative of a supposedly almost unanimous support among Crimea’s population as well as of the allegedly profound historical justification for the annexation has many supporters not only in Russia, but also among numerous Western politicians, journalists, experts, and diplomats. Often, these commentators consider themselves – in distinction to “idealistic” defenders of international law – as geopolitical “realists”, or even – in contrast to their overly emotional colleagues – as more “balanced” observers.

To yet greater extent, this problem is relevant for the discourse of the various German and other so-called Russland- or Putinversteher (Russia/Putin-understanders), meaning those publicists interested in Eastern Europe who consider themselves as exceptionally empathetic interpreters of the Russian “soul”. Based on their ostensible deep knowledge of Russia’s nature, past and destiny, the Russland-/Putinversteher typically expose considerable understanding and voice elaborate justifications for the Kremlin’s current foreign policies (Heinemann-Grüder 2015).

In many cases, the various apologetic narratives of Moscow’s annexation of Crimea ignore, however, the fact that the Russian propagandistic preparation, secret service operation and military intervention that led to Crimea’s transition had started already in late February 2014, if not earlier (Головченко & Дорошко 2016; Центр глобалистики «Стратегия XXI» 2016; Дорошко 2018). Not only many Russian, but also certain Western narrators of Moscow’s takeover of the Ukrainian peninsula flippantly or purposefully omit or downplay the fact that Crimea’s actual occupation by Russian troops had occurred already several days before the alleged “declaration of independence” by the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (hereafter: ARC) and city of Sevastopol on March 11, 2014, and the Kremlin’s official inclusion of these territories into the Russian Federation on March 18, 2014.

Yet, Russia’s military takeover of the Ukrainian Black Sea region prior to the various pseudo-legal acts on Crimea in early spring 2014 is an – if not the most – important facet of this rapid change of borders. The switch of real political control over the peninsula from Kyiv to Moscow had already been accomplished within the three weeks before the completion of the official process of Crimea’s official secession and formal incorporation into the Russian Federation. The entire transition processes had become possible only after a distinctly sudden and initially hidden, yet resolute seizure of the peninsula by Russian regular troops, irregular forces and local proxy groups, at the end of February and in early March 2014 (Березовець 2015).

Not only Moscow’s unapologetic military occupation of the peninsula, but also the following official course of Crimea’s separation from Ukraine and annexation to Russia grossly violated a number of fundamental international legal norms as well as certain provisions of the Constitutions of Ukraine, Crimea and even the Russian Federation itself. These facts are already well established and relatively thoroughly covered in the relevant Western and Ukrainian scholarly legal literature.

See Allison 2014; Heintze 2014; Luchterhandt 2014a, 2014b; Marxsen 2014, 2015; Peters 2014; Behlert 2015; Bílková 2015; Grant 2015; Singer 2015; Nikouei & Zamani 2016; Zadorozhnii 2016; Czapliński et al. 2017.

What has been lesser discussed so far are various political circumstances of the so-called “referendum” organized by the Kremlin on March 16, 2014 that also cast considerable doubt on the claim – still surprisingly popular among many Western politicians, journalists and diplomats – that the vast majority of the Crimean population had been craving for “reunification” with the Russian Federation, as well as on the assertion that there were supposedly weighty historical reasons for Moscow’s land-grab.

Not only Moscow’s unapologetic military occupation of the peninsula, but also the following official course of Crimea’s separation from Ukraine and annexation to Russia grossly violated a number of fundamental international legal norms as well as certain provisions of the Constitutions of Ukraine, Crimea and even the Russian Federation itself. These facts are already well established and relatively thoroughly covered in the relevant Western and Ukrainian scholarly legal literature.

The ambiguous results of the “referendum”

Oddly, one of the most critical early assessments illustrating the doubtfulness of the “referendum’s” officially announced results was made by three representatives of the Russian Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights (hereinafter Human Rights Council), one of Vladimir Putin’s official consultative bodies (Бобров 2014) [1]. A member of this authoritative Russian institution had made a private visit to Crimea in mid-April 2014. Based on his observations and conversations during this informal trip, as well as on other reports, three members of the Human Rights Council published an unofficial report on the Human Rights Council’s website (Бобров 2014).

In this statement, the three reputed activists claimed that, according to the estimates of “practically all interviewed experts and residents,” the percentage of Crimeans who took part in the “referendum” in the ARC was not 83.1%, as reported by the Crimean authorities that had fallen under Kremlin control, but rather somewhere between 30% to 50%. In the estimation of the three Russian human rights defenders, the annexation was supported not by 96.77 % of the alleged participants of the “referendum,” as reported by the Moscow-directed Crimean authorities, but by only by 50% to 60% of the Republic’s voters (Бобров 2014; Peters 2014).

The latter figure roughly corresponds to the average results of various surveys on the accession of Crimea to Russia held on the peninsula prior to the annexation[2]. The critical assessment of the alleged results of the voting held on Crimea on March 16, 2014, by three members of the Russian Human Rights Council, is supported by a brief statistical analysis, by Aleksandr Kireev, of the dynamics of the officially reported turnout for the pseudo-referendum (Киреев 2014). The suspicious attendance data presented by Kireev suggests a likely large-scale falsification of voting results. The conclusions of the informal report submitted by the Russian human rights defenders go in the same direction as an even lower estimate of Crimean voter turnout, by the Mejlis (council) of the Crimean Tatars, the executive organ of the peninsula’s indigenous population’s representative body [3].

Mustafa Dzhemilev

Based on these estimates, it would appear that only less than a third of Crimea’s population may have actually casted its votes for acceding to Russia. This would seem to be the case even if one factored in a probably higher turnout and stronger support for the annexation, in the city of Sevastopol, the base of Russia’s Black Sea fleet. The likely overall and rather low approximate percentage of Crimean votes cast for the annexation is not sufficient to even partially justify such a significant change of borders in post-Cold War Europe. Moreover, the report by the Russian Human Rights Council quoted political experts in Crimea who reported to them that “residents of Crimea voted rather for terminating, as they put it, ‘the terrible corruption and the use of force by the thieves from Donetsk’ [installed in republican offices, by Yanukovych’s administration in 2010-2013 – A.U.] than in favour of accession to Russia” (Бобров 2014) [4].

Why polls carried out later cannot legitimize the “referendum”

According to the last relevant pre-annexation poll in mid-February 2014, i.e. a few days prior to the start of Crimea’s occupation by Russian soldiers without insignia, 41% of the respondents in the ARC, i.e. excluding the city of Sevastopol, supported then the merger of Russia and Ukraine into one state – such was the question posed by the Ukrainian sociological service (KIIS 2014). This result roughly matches the average results of earlier polls concerning a possible accession of the peninsula to Russia (Podolian 2015). In stark contrast to numerous pre-annexation polls, various opinion surveys conducted after the seizure of the Black Sea peninsula by Russia, seem to be demonstrating nothing less than doubling of popular support for Crimea’s inclusion into Russia. Ever since the annexation in March 2014, among Crimean residents, the share of those supporting the peninsula’s incorporation into the Russian Federation has been usually higher or even considerably higher than 80% [5]. For the following reasons, the seemingly unambiguous results obtained after the annexation operation are, however, of only limited significance to an interpretation of the events that took place on Crimea, in early 2014 (Sasse 2017).

According to the last relevant pre-annexation poll in mid-February 2014, i.e. a few days prior to the start of Crimea’s occupation by Russian soldiers without insignia, 41% of the respondents in the ARC, i.e. excluding the city of Sevastopol, supported then the merger of Russia and Ukraine into one state – such was the question posed by the Ukrainian sociological service.

First, the results of recent polls should be – at least, partially – considered in light of the extremely aggressive anti-Ukrainian defamation campaign conducted by pro-Kremlin TV and radio channels as well as Russian newspapers – the only mass media sources available to Crimeans since March 2014 (Fedor 2015). Second, some interpretations of more recent polls, according to which the vast majority of respondents on Crimea support the annexation, do not take sufficiently into account a tendency among voters to opt for following earlier paths of development once they have been freely or forcibly chosen, and to support the respectively current status quo. Decisions expressed in popular polls are affected not only by voters’ ideological preferences, but also by other factors such as social conformism, psychological inertia, collective pressure, and strategic calculation.

Weighty choices are often made, to one or another degree, path-dependently. They – consciously nor not – consider the possible severity, inconveniences and risks of changing a previously embarked upon political direction. Polls – especially, on such fundamental issues as statehood, borders and security – thus reflect not only the narrowly defined political positions of respondents. They also express many voters’ inclination to try maintaining the present state of affairs and their desire to preserve public concord. An example for the effects of this psychological mechanism was the referendum on Scotland’s independence, also conducted in the year 2014. In this – in distinction to the Crimean pseudo-referendum – fully legal, properly prepared and universally accepted plebiscite, eventually 55.3% of a population, of which about 84% consider themselves Scots and where separatist tendencies have always been strong, voted against independence of their region from the United Kingdom.

Interestingly, prior to 2014, voters’ general preference for maintaining an acceptable status quo had starkly “pro-Ukrainian” consequences on Crimea. Despite unquestionably strong pro-Moscow sentiments among many ethnically Russian Crimeans already prior to the Kremlin’s propagandistic preparation of the annexation, there had been a relatively high level of political stability on the peninsula, over the previous 20 years (Sasse 2014). This was a result of, among others, the mentioned partial dependency of human beings’ preference for continuing the previously chosen path and for supporting any current order, as long as it does not contradict the fundamental interests of the people in question.

Protest of the Crimean Tatars

At least, that seems to be the implication of a series of in-depth interviews conducted by British political scientist Eleanor Knott (2018), within her field research on Crimea, several months before the start of the Euromaidan. Knott’s investigation revealed that Crimeans with strongly and otherwise unanimously pro-Moscow views, when being asked “either/or” questions about where Crimea should belong, replied surprisingly conformist and non-separatist. In these interviews, taken on Crimea in 2012-2013, even radically pro-Russian respondents opted to preserve the peninsula as a part of Ukraine and did not demand its annexation to the Russian Federation (Knott 2018). This, at first glance, unexpected preference among pro-Moscow Crimeans was, probably, no indicator of substantive sympathy for the Ukrainian state. Instead, it reflected these ethnic Russians’ desire to preserve stability, predictability and peace in their home region.

Thirdly, some observers, who refer to sociological research conducted on Crimea after the annexation, underestimate or even entirely ignore the real or perceived risks that potentially pro-Ukrainian or simply non-pro-Moscow respondents run and are afraid to run when answering questions about their desired status for Crimea. Oppositional Crimeans on the occupied peninsula need to have, since March 2014, considerable courage and resoluteness to express their views openly. They will have to be ready to do so in spite of – rightly or wrongly – anticipating possible persecution against themselves and their close ones (family, friends, colleagues) as a result of voicing their doubts about the annexation in front of strangers, i.e. the more or less anonymous interviewers from (supposedly) sociological services. Political positions that may be dangerous to articulate today on Crimea include doubts about the legitimacy or/and legality of the Russian annexation, regrets about the political detachment of the peninsula from Ukraine, or an approval of a return of the peninsula under Kyiv’s control. Given the new political and legal situation in this Black Sea region, since the start of its occupation in late February 2014, pronouncing such sentiments or even expressing mere sympathy for Ukraine can lead to all kinds of problems.

Political positions that may be dangerous to articulate today on Crimea include doubts about the legitimacy or/and legality of the Russian annexation, regrets about the political detachment of the peninsula from Ukraine, or an approval of a return of the peninsula under Kyiv’s control.

After being annexed by Moscow, the Black Sea peninsula has become one of the European regions with the highest levels of limitations of basic political and civil rights (UNHCR 2017). Since 2014, disapproval of the so-called “reunification” of Crimea with Russia has become increasingly stigmatized by pro-Kremlin media and the externally installed new authorities on Crimea. In a – probably, often anticipated – worst-case scenario, expression of such a position can have serious consequences for respondents if, for instance, the survey is wiretapped or simply staged by Russia’s special services – dangers that many citizens of Crimea are, probably, well aware of.

Since 2014, the notoriously rigid so-called “anti-extremist” and “anti-separatist” Russian laws are being applied on Crimea, in order to suppress political opposition. Moscow and its local representatives continually persecute dissent on the peninsula. This is especially the case with regard to pro-Ukrainian members of the Crimean Tatar minority. Sometimes, it concerns simply sympathizers of Ukrainian symbols and culture (Halbach 2015; KHPG 2016-2018) [6]. For these and similar reasons, the consequences of political criticism of the annexation, remorse about the separation from Ukraine, or a recognition of Crimea as belonging to the Ukrainian state, remain unpredictable for respondents to sociological polls.

To be sure, the situation on Crimea today is very different from that in the Soviet bloc, before the mid-1980s. Under totalitarianism, countless official polls and votes had been seemingly indicating ridiculously high public support for the communist leaders and regimes until shortly before they were toppled in popular uprisings. Fear of unpredictable future repercussions of expressing political dissent is, presumably, today much lower on Crimea than during Soviet times. Yet, such dreads probably do exist among many pro-Ukrainian-minded, Moscow-critical or simply neutral Crimeans these days. Hence, it seems likely that some or even many of them either refuse to participate or do neither fully nor honestly express their opinions in polls about the status of the peninsula.

One should thus be cautious about post-annexation research results on political attitudes of Crimeans. This scepticism even applies to those surveys conducted by well-known Western opinion polling institutions working on the peninsula, since 2014. In conclusion, post-annexation survey data have only limited value for assessing the real popular support for Russia’s seizure of Crimea, before Moscow began its systematic preparation and swift implementation in early 2014.

The curious course of the “referendum”

Looking back at the events of spring 2014, there are other reasons questioning the pseudo-referendum’s result and cautioning against a lenient attitude towards official Russian interpretations of Crimea’s annexation. The “referendum’s” preparation, procedure, media coverage, and ballot were so manifestly biased that this poll can serve as a textbooks example for manipulation of voting. The date of the “referendum” was changed twice in a short period of time. The residents of Crimea had neither the time nor the opportunity to discuss openly, freely and critically the alternatives they would have to choose from during the approaching popular vote on March 16, 2014 (Podolian 2015).

Before the referendum, the OSCE, therefore, publicly refused to send observers to the “referendum” and stated: “International experiences […] showed that processes aiming at modifying constitutional set ups and discussions on regional autonomy were complex and time consuming, sometimes stretching over months or even years […]. Political and legal adjustments in that regard had to be consulted in an inclusive and structured dialogue on national, regional and local level” [7].

These conditions were not met. Thus, not only the OSCE, but all other competent international governmental and non-governmental electoral monitoring organizations refused to send their representatives. Instead, the Kremlin invited several dozen representatives of foreign radical and, in most cases, marginal political groups. These guests were later presented to Russian TV viewers as “international observers” that approved of the legitimacy and orderliness of the “referendum” (Shekhovtsov 2014, 2015; Coynash 2016).

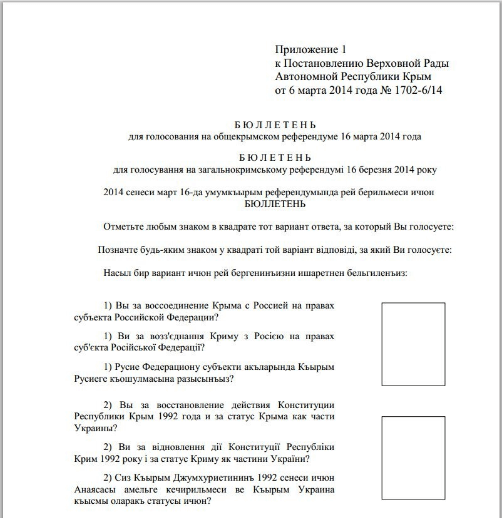

That was in spite of the visually documented fact that the vote happened under conditions of tangible psychological pressure caused by demonstrative presence of Russian soldiers without insignia – the notorious “little green men” or, in Kremlin parlance, “polite people” – as well as of armed pro-Moscow irregulars from various Crimean and Russian paramilitary groups. It was also strange that among the alternatives offered in the “referendum” there was no option to vote for a simple preservation of the existing status quo, that is of the then valid Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea adopted in 1998 (Giles 2014). Instead, Crimean voters had two options, each offering to change the legal status of Crimea – either annexation of the peninsula to the Russian Federation, or a return to some older constitution of the ARC from 1992. Both of these ballot options, moreover, were phrased ambivalently – and arguably, to some degree, absurd.

That was in spite of the visually documented fact that the vote happened under conditions of tangible psychological pressure caused by demonstrative presence of Russian soldiers without insignia – the notorious “little green men” or, in Kremlin parlance, “polite people” – as well as of armed pro-Moscow irregulars from various Crimean and Russian paramilitary groups.

“Russia,” the All-Russian Empire and the Russian Federation

The first option in the pseudo-referendum promised Crimeans a “reunification of Crimea with Russia” (vossoedinenie Kryma s Rossiei). However, as anybody with elementary knowledge of East European history and geography would know, Crimea had never been part of a “Russia” separate from much of the dry territory of the post-Soviet Ukrainian state to which the peninsula has belonged since 1991. Most of modern continental Ukraine was, just like Crimea, a part of, first, the Tsarist Empire, and, later, the Soviet Union. Those two states were, apparently, meant by the word “Russia” in the 2014 “referendum”.

The Kremlin was here playing with terminology in that it purposefully abused the multiple connotations of the word “Russia.” The term “Russia” can denote, depending on the context, the Tsarist Empire, the (politically irrelevant) Russian Republic within the USSR, the Soviet Union as a whole, or the post-Soviet Russian Federation. Despite the primitiveness of this and other similar verbal games in relation to Ukraine (“fascism,” “putsch,” “separatists,” “civil war,” etc.), such manifest manipulations of the meanings of key terms continue to affect many Western observers.

Crimea belonged from 1783 to 1917 to the All-Russian Empire, but this former “Russia” does obviously not correspond to the modern Russian nation state (Furman 2011). Much of the dry territory of modern Ukraine, and not just Crimea, once belonged to both, the Tsarist and Soviet states – as did the territory of almost the entire modern Russian Federation. Both post-Soviet republics, the Russian Federation and independent Ukraine, are thus successor states to the “Russia” with which Crimea was promised “reunification” in the pseudo-referendum of 2014.

In the West, many still do not seem to fully understand that the Crimean peninsula was never part of a mythical Russian nation state existing separately from most of today’s mainland Ukraine. The only land-based connection between Crimea and the territory of – what is today considered – “Russia,” in imperial and Soviet times, were the southeastern dry lands of today Ukraine. This was also the area of the Tsarist Empire via which Catherine the Great took control over Crimea, in the late 18th century, deploying, moreover, many Ukrainian-speaking soldiers in this operation. The larger part of left-bank Ukraine, i.e. its mainland eastern and southern parts, as well as right-bank Kyiv had belonged to the Tsarist Empire already before Catherine’s capture of Crimea. The larger part of right-bank Ukraine, i.e. today mainland central, southwestern and western Ukraine, was attached to the Tsarist Empire within a few years after Crimea’s annexation, between 1783 and 1795, as a result of the so-called second and third partitions of Poland, as well as after a victorious war against the Ottoman Empire.

For these and other reasons, Crimea could not have been detached from the Russian Federation that had only emerged in 1991. Accordingly, it could not be “reunited” with it in 2014. In 1991, Ukraine in its entirety, including the Black Sea peninsula belonging geologically and historically to it, departed from “Russia,” i.e. the Soviet empire. An even partial acknowledgement of Moscow’s historical justification of the 2014 annexation amounts to a recognition of Russian imperial irredentism as an ordering principal for the post-Soviet world. This, in turn, would entail an acceptance of Russian claims to many more lands outside the current Federation. Some of these territories had become parts of the Tsarist Empire, at about the same time as, earlier than, or even much earlier than, Crimea.

An even partial acknowledgement of Moscow’s historical justification of the 2014 annexation amounts to a recognition of Russian imperial irredentism as an ordering principal for the post-Soviet world. This, in turn, would entail an acceptance of Russian claims to many more lands outside the current Federation.

It is true that ethnic Ukrainians never dominated Crimea’s population – neither after the accession of the peninsula to the Tsarist Empire in 1783, nor after its inclusion into the Soviet Union in 1922, or after Ukraine’s independence in 1991. Yet, by the end of the 19th century, the ethnic group still constituting the relative majority of residents of the peninsula were the indigenous Crimean Tatars, most of whom are today strongly pro-Ukrainian. Only later, during the 20th century, ethnic Russians became, first, the relative and, later, the absolute majority within Crimea’s population. This was a result of the Tsarist and Soviet regimes’ brutal demographic engineering of the peninsula, i.e. the purposeful settling of Eastern Slavs on Crimea, as well as the systematic eviction, deportation, suppression and, partly, annihilation of the Crimean Tatars as well as other non-Slavic ethnic minorities of the peninsula.

Contrary to widespread public perception in Russia and the West, today’s predominantly “Russian” demography of Crimea is thus a fairly young historic phenomenon. Moreover, it is, to considerable degree, the result of Moscow’s mass violence against Crimean Tatars as well as other non-Russians on Crimea. The historical connection of Crimea to the post-Soviet Russian Federation – and not to today Ukraine, favoured by most Crimean Tatars – is fragile for other reasons too.

Under Tsarism, Crimea belonged to the All-Russian Empire’s Tauric Gouvernement (Tavriya) from 1802 to 1917. This large administrative district encompassed not only the Black Sea peninsula, but also a significant part of southeastern mainland Ukraine, connected to Crimea through the Isthmus of Perekop. The dry part of the Tavriya province was demographically larger than Crimea, and its population consisted predominantly of Ukrainians or “Small Russians,” in Tsarist imperial terminology (Головченко & Дорошко 2016, 75). According to the population census of 1897, the entire Tauric Gouvernement, i.e. Crimea and the mainland part to the north of the peninsula, had approx. 1.4 million residents. Of them, about 0.4 million were Russophones, and about 0.6 million were Ukrainian-speakers [8]. Of the then circa 0.55 million inhabitants of the Tauric Gouvernement’s peninsula, 35.5% were Crimean Tatars, 33.1% were ethnic Russians, and 11.8% were ethnic Ukrainians [9]. Thus, the Tsarist-Tauric period of the Crimean past, that lasted for over 100 years, establishes an administrative-historical connection of the peninsula with the territory of present-day continental Ukraine as well as with the pro-Ukrainian Crimean Tatars rather than with the modern Russian Federation or nation [10].

Crimea’s past as a part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) in 1921-1954 is often referred to by Russian supporters and Western apologists of the annexation. Yet, not only should this period be contrasted to the following longer period of Crimea’s belonging to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (UkrSSR) in 1954-1991. Neither the RSFSR, although it had briefly existed already before the foundation of the USSR in 1922, nor the UkrSSR, although it was – unlike the RSFSR – an official member of the UN since 1945, were recognized independent states.

Moreover, the by far largest and most violent as well as murderous change of population on the peninsula falls into the RSFSR period of Crimean history. In 1944, Stalin ordered a brutal mass deportation of Crimean Tatars as well as several other minorities from the peninsula to Central Asia (Crimea’s relatively significant German minority had been deported by force, already in 1941). As a result of this purposeful ethnic cleansing, a significant part of the native population of Crimea perished, and, only then, the ethnic Russians became an absolute majority on the peninsula.

Having once been the predominant ethnic group on the peninsula, the Crimean Tatars today comprise, according to different statistics, about 10-12 % of Crimea’s population. Their geopolitical preferences have been principally shaped by their ruthless repression by Moscow since 1783, Stalin’s mass deportation of 1944 as well as their later return to the peninsula and reintegration into their homeland, i.e. into the late UkrSSR and post-Soviet Ukraine. Crimean Tatars’ views on the Russian-Ukrainian conflict are also heavily informed by the cult of Stalin in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia (Magocsi 2014; Беліцер 2016; Hottop-Riecke 2016). These and similar historical experiences of Crimean Tatars and their organizations explain their staunch support for the sovereignty and integrity of the post-Soviet Ukrainian state, and their predominant consent to a return of Crimea to Ukraine (and much weaker demand for an independent Crimea). The pro-Ukrainian position of the Crimean Tatars and history of their deportation came briefly to the attention of a wider European public through the victory, for Ukraine, of the Crimean Tatar singer Jamala, with her song “1944,” in the 2016 Eurovision Song Contest (Wilson 2017, 15).

The pro-Ukrainian position of the Crimean Tatars and history of their deportation came briefly to the attention of a wider European public through the victory, for Ukraine, of the Crimean Tatar singer Jamala, with her song “1944,” in the 2016 Eurovision Song Contest.

Developments during Crimea’s Soviet period can thus hardly be used as historical arguments in favour of the 2014 Russian annexation. They have limited relevance for current affairs, since they refer to episodes within the history of a highly centralized former empire. The Soviet Union was a totalitarian state where the inclusion of Crimea into the RSFSR in 1922, and the economically motivated transfer of the peninsula from the RSFSR to the UkrSSR in 1954 had largely administrative purposes and only little political meaning (Jilge 2015).

Moreover, there were several cases of territorial transfers, within the USSR, that put under question the logic of the annexation’s apologists’ reference to the 1954 shift. For instance, during a change of administrative boundaries inside the young USSR in 1925, the UkrSSR had lost, to the benefit of the RSFSR and Belarusian SSR, territories larger than the territory of Crimea it gained in 1954 (Головченко & Дорошко 2016, 91). Nevertheless, until 2014, no representative of the Ukrainian political elite had put forward any official territorial claims to neighbouring countries based on these facts or with reference to the numerous pre-revolutionary maps where the territory of “Ukraine” exceeds – partly, by far – the territory of the post-Soviet Ukrainian state. Such historical narratives, megalomaniac views, and irredentist plans remained the prerogative of extreme and marginal political movements in Ukraine, as in most countries, before the Russian aggression. Only after the start of the Russian-Ukrainian war, mainstream public Ukrainian rhetoric concerning, for example, Russia’s southern Kuban region has, in response to the sudden claims by the Kremlin, become more provocative.

Building a bridge across the Kerch Strait

The post-Soviet leadership of Russia, despite many political disputes concerning the peninsula and especially Sevastopol, had never officially questioned Crimea’s inclusion into post-Soviet Ukraine, until 2014. Notwithstanding numerous unofficial political announcements by Russian politicians and some revanchist declarations of the Russian parliament after 1991, post-Soviet Russia formally and repeatedly affirmed the peninsula’s belonging to the Ukrainian state in several treaties and agreements (Kuzio 2007). The two legally most important documents, in which Moscow has recognized Crimea as part of Ukraine, are the tripartite 1991 Russian-Ukrainian-Belarusian Belavezha Accords on the dissolution of the USSR, and the bilateral 2003 Russian-Ukrainian Border Treaty.

Both agreements were ratified by the Russian and Ukrainian parliaments in accordance with due procedure and signed by the respective Presidents of Russia and Ukraine. An official press release from the Russian Presidential Administration on Putin’s signing of the law on the ratification of the border agreement between Russia and Ukraine in 2004 says: “The administrative border existing between the RSFSR and the UkrSSR at the moment of the collapse of the USSR was taken as the basis [of the treaty], in accordance with the [border’s] determination in the relevant state legal acts” [11].

The unclear alternative to annexation in the “referendum”

The second option in the pseudo-referendum of March 16, 2014 offered Crimeans a return to the ARC’s constitution of 1992. Yet, its wording was even more confusing than that of the first option and its promise of a “reunification” of the peninsula with “Russia.” The paradox of the second question of the “referendum” was that, during the year 1992, two relatively different versions of the ARC’s Constitution had been adopted by the Republic’s Supreme Council [12]. Deliberately or not, it was left unclear, in the 2014 “referendum,” which of these two alternative republican basic laws the question actually referred to. The voters were simply asked: “Are you for the restoration of the 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Crimea and for the status of Crimea as a part of Ukraine?”

It remained uncertain to the public, media and voters, however, exactly what constitutional text of 1992 the ballot’s second question had in mind. Was the “referendum’s” question offering a return to the more “confederative” version of the Crimean Constitution of May 1992, or a re-introduction of the somewhat later, yet significantly changed and more “federative” version of the Constitution adopted in September 1992? The paradox was that both 1992 versions of the Constitution had established Crimea as a “part of Ukraine,” as formulated in the “referendum.” In the May 1992 version of the Constitution, Article 9 stated that Crimea “is included in the state Ukraine” (vkhodit v gosudarstvo Ukraina) [13]. In the significantly modified September 1992 version of the Constitution, this assertion was additionally supported in Article 1, by the phrase that Crimea lies “within Ukraine” (v sostave Ukrainy) [14]. Although both 1992 versions of the Constitution thus saw Crimea as belonging to Ukraine, these two texts departed in many other ways from each other, and defined the status as well as institutions of Crimea differently.

Had the majority of Crimeans opted for this second choice during the “referendum,” the newly created satellite government in Simferopol could apparently have chosen from the two different versions of the 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Crimea, at its own will. The Moscow stooges in, and not the population of, Crimea could have decided which text of the Crimean Constitution would have been adopted. There is a suspicion that the “referendum’s” strangely ambivalent second question was deliberately put in vague terms instead of offering the, for these types of referenda, usual option of a simple preservation of the status quo (Giles 2014). Perhaps, this, at its core, incomprehensible alternative to supporting a plain annexation was designed to increase the likelihood of choosing the first, much clearer option – full inclusion into the Russian Federation. In March 2014, the alternative put before Crimea’s residents was not so much a choice between Russia and Ukraine than one between a clear and blurry future.

The historical facts and political information listed in this article are neither unusual, nor secret or new [15]. They and some similarly revealing aspects of the noteworthy events of February-March 2014 are common places in today Ukraine. They are well-known to regional experts at Western universities and think-tanks, as well as to Eastern Europe specialists in European governments, political and civil organizations.

Nevertheless, many Western observers who do not hesitate to voice publicly comments on the past, annexation and future of Crimea do not seem to know or, worse, are choosing to ignore some or even most of the mentioned facts. Instead, many of them, at least, partially follow the Kremlin’s apologetic narrative for the annexation: A, perhaps, somewhat bent referendum ultimately led to a change of borders which (allegedly) was overwhelmingly demanded by Crimeans, and which corrected some (mythical) historical injustice.

Footnotes

* A different version of this article was initially written for German readers and published in the open political science journal Sirius: Zeitschrift für Strategische Analysen. It was then translated, edited and modified by VoxUkraine, in Ukrainian, Russian, and English.

[1] For a list of some of the earliest relevant comments by critical Western experts on the pseudo-referendum, see: Podolian 2015, 122-128.

[2] An incomplete review of some relevant surveys can be found, in English, here, and, in Russian, here: Илларионов 2018.

[3] A short summary may be found here in English.

[4] See also: Wilson 2017.

[5] Some relevant quotes, sources and other information on this issue may be found here.

[6] «Скоро начнут сажать за мысли об Украине» – из крымских сетей // Крым.Реалии, 5.5.2018.

[7] OSCE Chair says Crimean referendum in its current form is illegal and calls for alternative ways to address the Crimean issue // ОSCE, 11.3.2014.

[8] Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Распределение населения по родному языку, губерниям и областям // Демоскоп Weekly

[9] Some relevant data and sources may be found here.

[10] “Ukrainian historians [furthermore] point to a long history of earlier engagement [before 1783], with local Ukrainian Cossacks having a more intimate interaction with the peninsula than the northerly Muscovite state.” Wilson 2017, 4-5, with reference to: Смолій 2015. See also: Громенко 2016.

[11] President Vladimir Putin signed a law ratifying the Treaty between Russia and Ukraine on the Russian-Ukrainian State Border // President of Russia, 23.4.2004.

[12] For some more elaboration, see: Умланд 2016.

[13] Constitution of the Republic of Crimea // Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, 6.05.1992.

[14] Law of the Republic of Crimea “On Amendments to the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea” // Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, 25.9.1992.

[15] For more information in English, see: Transitions Online 2015.

References

Беліцер, Наталя (2016): Кримські татари як корінний народ. Історія питання і сучасні реалії. Київ.

Березовець, Тарас (2015): Анексія: острів Крим. Хроніки «гібридної війни». Київ.

Бобров, Евгений (2014): Проблемы жителей Крыма // Блоги членов Совета, 22.4.

Дорошко, Микола (2018): Неоголошені війни Росії проти України у ХХ – на початку ХХІ ст. Причини і наслідки. Київ.

Головченко, Володимир, Дорошко, Микола (2016): Гібридна війна Росії проти України. Історико-політичне дослідження. Київ.

Громенко, Сергій, ред. (2016): Наш Крим. Неросійські історії українського півострова. Київ.

Илларионов, Андрей (2018): Центр Разумкова: «Мы не нашли цифр, представленных в интервью» // Livejournal, 25.7.

Киреев, Александр (2014): О неправдоподобной динамике явки по районам и городам Крыма // Livejournal, 16.3.

Смолій, Валерій, ред. (2015): Історія Криму в запитаннях та відповідях. Київ.

Умланд, Андреас (2016): Странности кремлёвского «референдума» в Крыму // Новое время, 19.9.

Центр глобалистики «Стратегия XXI» (2016): Гибпрессия Путина. Невоенные аспекты войн нового поколения. Киев.

Allison, Roy (2014): Russian “Deniable” Intervention in Ukraine. How and Why Russia Broke the Rules // International Affairs. Vol. 90. № 6. Pp. 1255–1297.

Behlert, Benedikt (2015): Die Unabhängigkeit der Krim. Annexion oder Sezession? // IFHV Working Paper. Vol. 5. № 2.

Bílková, Veronika (2015): The Use of Force by the Russian Federation in Crimea // Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht. Vol. 75. Pp. 27-50.

Coynash, Halya (2016): Myth, “Observers” and Victims of Russia’s Fake Crimean Referendum // Human Rights in Ukraine, 16.3.

Czapliński, Władysław, Sławomir Dębski, Rafał Tarnogórski & Karolina Wierczyńska, eds (2017): The Case of Crimea’s Annexation Under International Law. Warsaw.

Fedor, Julie, Ed. (2015): Russian Media and the War in Ukraine // Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society. Vol. 1. № 1. Pp. 1-300.

Furman, Dmitrij (2011): Russlands Entwicklungspfad. Vom Imperium zum Nationalstaat // Osteuropa. Vol. 61. № 10. Pp. 3–20.

Giles, Keir (2014): Crimea’s Referendum Choices Are No Choice at All // Chatham House, 10.3.

Grant, Thomas D. (2015): Aggression against Ukraine. Territory, Responsibility, and International Law. London.

Halbach, Uwe (2014): Repression nach der Annexion. Russlands Umgang mit den Krimtataren // Osteuropa. Vol. 64. №№ 9-10. Pp. 179–190.

Heinemann-Grüder, Andreas (2015): Lehren aus dem Ukrainekonflikt. Das Stockholm-Syndrom der Putin-Versteher // Osteuropa. Vol. 65. № 4. Pp. 3-24.

Heintze, Hans-Joachim (2014): Völkerrecht und Sezession – Ist die Annexion der Krim eine zulässige Wiedergutmachung sowjetischen Unrechts? // Humanitäres Völkerrecht. Informationsschriften. Vol. 27. № 3. Pp. 129-138

Hottop-Riecke, Mieste (2016): Die Tataren der Krim zwischen Assimilation und Selbstbehauptung. Der Aufbau des krimtatarischen Bildungswesens nach Deportation und Heimkehr (1990-2005). Stuttgart.

Jilge, Wilfried (2015): Geschichtspolitik statt Völkerrecht. Anmerkungen zur historischen Legitimation der Krim-Annexion in Russland // Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 27.2.

KHPG (2016-2018): Human Rights Abuses in Russian-Occupied Crimea // Human Rights in Ukraine.

KIIS (2014): How Relations between Ukraine and Russia Should Look Like? Public Opinion Polls’ Results // Kiev International Institute of Sociology, 4.3.

Knott, Eleanor (2018): Identity in Crimea before Annexation. A Bottom-up Perspective // Pål Kolstø & Helge Blakkisrud, eds: Russia Before and After Crimea. Nationalism and Identity, 2010–17. Edinburgh. Pp. 282-305.

Kuzio, Taras (2007): Ukraine – Crimea – Russia. Triangle of Conflict. Stuttgart.

Luchterhandt, Otto (2014a): Die Krim-Krise von 2014. Staats- und völkerrechtliche Aspekte // Osteuropa. Vol. 64. №№ 5-6. Pp. 61–86.

Luchterhandt, Otto (2014b): Der Anschluss der Krim an Russland aus völkerrechtlicher Sicht // Archiv des Völkerrechts. Vol. 52. № 2. Pp. 137-174.

Magocsi, Paul Robert (2014): This Blessed Land. Crimea and the Crimean Tatars. Toronto.

Marxsen, Christian (2014): The Crimea Crisis. An International Law Perspective // Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht. Vol. 74. Pp. 367-391.

Marxsen, Christian (2015): Territorial Integrity in International Law – Its Concept and Implications for Crimea // Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht. Vol. 75. Pp. 7-26.

Nikouei, Majid & Masoud Zamani (2016): The Secession of Crimea. Where Does International Law Stand? // Nordic Journal of International Law. Vol. 85. Pp. 37-64.

Peters, Anne (2014): Das Völkerrecht der Gebietsreferenden. Das Beispiel der Ukraine 1991-2014 // Osteuropa. Vol. 64. №№ 5-6. Pp. 101–134.

Podolian, Olena (2015): The 2014 Referendum in Crimea // East European Quarterly. Vol. 43. № 1. Pp. 111-128.

Sasse, Gwendolyn (2014): The Crimea Question. Identity, Transition, and Conflict. Cambridge, Mass.

Sasse, Gwendolyn (2017): Terra Incognita. The Public Mood in Crimea // ZOiS Report. № 3.

Shekhovtsov, Anton (2014): Pro-Russian Extremists Observe the Illegitimate Crimean “Referendum” // Voices of Ukraine. 17.3.

Shekhovtsov, Anton (2015): Far-Right Election Observation Monitors in the Service of the Kremlin’s Foreign Policy // Marlene Laruelle, ed.: Eurasianism and the European Far Right. Reshaping the Europe-Russia Relationship. Lanham. Pp. 223-243.

Singer, Tassilo (2015): Intervention auf Einladung // Evgeniya Bakalova, Tobias Endrich, Khrystyna Shlyakhtovska & Galyna Spodarets, eds: Ukraine. Krisen. Perspektiven. Interdisziplinäre Betrachtungen eines Landes im Umbruch. Berlin. Pp. 235-260.

Transitions Online (2015): Crimea. The Anatomy of a Crisis. Prague.

Umland, Andreas (2017): Kremlin Narratives on Crimea Resurface in German Election Debate // European Council on Foreign Relations, 19.9.

UNHCR (2017): The situation of human rights in the temporarily occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol (Ukraine), Kyiv.

Wilson, Andrew (2017): The Crimean Tatar Question. A Prism for Changing and Rival Versions of Eurasianism // Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society. Vol. 3. № 2. Pp. 1-46.

Zadorozhnii, Oleksandr (2016): Russian Doctrine of International Law after the Annexation of Crimea. Amazon.

ANDREAS UMLAND is Senior Fellow at the Institute for Euro-Atlantic Cooperation in Kyiv, and editor of the ibidem Press book series “Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society.”