Academics and central bankers agree that management of expectations is a key tool for macroeconomic stabilization. While giving a speech at the 2005 Jackson Hole conference, Michael Woodford famously declared, “[for monetary policy to be most effective] not only do expectations about policy matter, but, at least under current conditions, very little else matters.” So policymakers have to be extremely careful in choosing words to navigate the economy and keep the markets calm. This is the art that many in Ukraine are yet to learn.

Indeed, an avalanche of statements about the future course of monetary policy unnerved households and firms. For example, the minister of economy suggested that inflation should be well above the official target of 5 percent per year. The head of the Council of the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) repeatedly suggested “productive emissions”, i.e. printing money, to stimulate the economy. The President of Ukraine stated that he would like to see the national currency to depreciate from 27 UAH/USD to 30 UAH/USD. What are the possible consequences of these public statements?

While low inflation may be a sign of depressed economy and some effort to raise inflation expectations may be justified under certain conditions, one should keep in mind that inflation processes are highly complex. In particular, households and firms often associate inflation with bad economic outcomes such as high unemployment and low output growth. This fact holds true in both emerging and advanced economies. This is remarkable because even in a low inflation environment of advanced economies where some inflation may be helpful in defeating deflationary spirals and other adverse effects of economic depressions, people believe that inflation is bad. This joint distribution of expectations for inflation and real economy suggests that one should exercise utmost caution when talking about high or rising inflation because such talks can trigger elevated inflation expectations (and hence inflation) as well as a pessimistic economic outlook. In other words, policies that raise inflation expectations will not help the economy. Such policies will backfire: instead of consuming more, households will consume less; instead of hiring more workers and making larger investments, firms will reduce employment and cut investment. Why? Because inflation is a bad thing and one should prepare for worse times. This empirical pattern is supported by many studies, including randomized controlled trials.

How much difference does it make for Ukraine? Using data from a NBU’s survey of firm managers, we investigate the correlation between expected exchange rate, inflation, and business conditions. The results are striking.

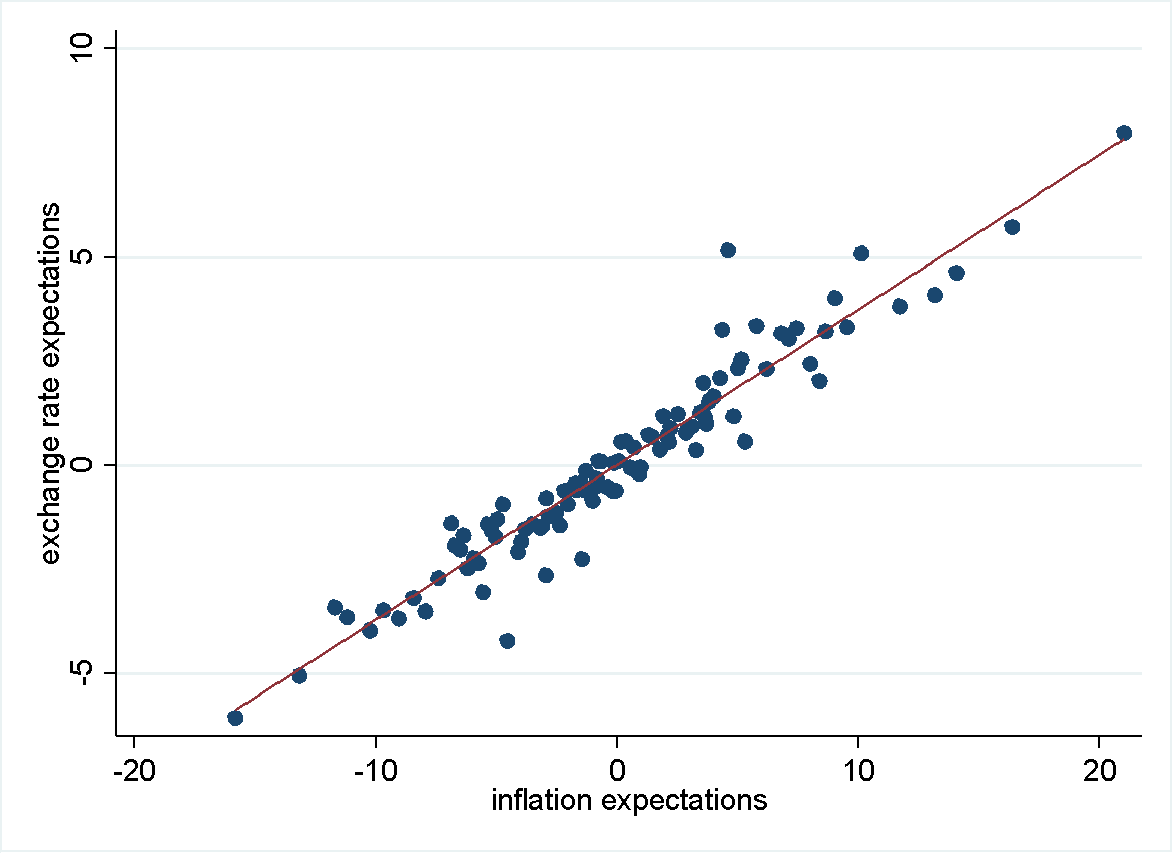

Figure 1 shows that managers expecting a weaker hryvnia (that is, it takes more hryvnias to buy a dollar) also expect a higher inflation. Consistent with previous studies, the relationship is very strong. While this is only a correlation, other studies suggest that there is likely a causal relationship as well. This relationship means that by telling people that the exchange rate will depreciate by 10 percentage points (this would imply a depreciation from 27 to 30 UAH/USD, for example) will likely lead to a 3 percentage point increase in expected inflation, a large magnitude. For Ukraine, a country with a history of chronically high inflation, such an increase in inflation expectations is a dangerous development that may cost dearly in the future.

Figure 1. Joint distribution of expectations for inflation and exchange rate.

Notes: the figure plots a binscatter for the joint distribution of expectations for exchange rate and inflation in the next 12 months. For each variable, we take out the time fixed effect and so all variables are mean zero. Inflation expectations are for the-one year ahead horizon. Inflation expectations are reported as answers to multiple choice questions (typically 7-9 options; e.g., the bins could be “less than 5%”, “5 to 10%”, “10 to 15%”, …, “more than 40%”). Exchange rate expectations are measured as percent depreciation (positive values on the vertical axis) or appreciation (negative values). Expected exchange rate is also reported as answers to multiple choice questions. The sample period is 2010-2020.

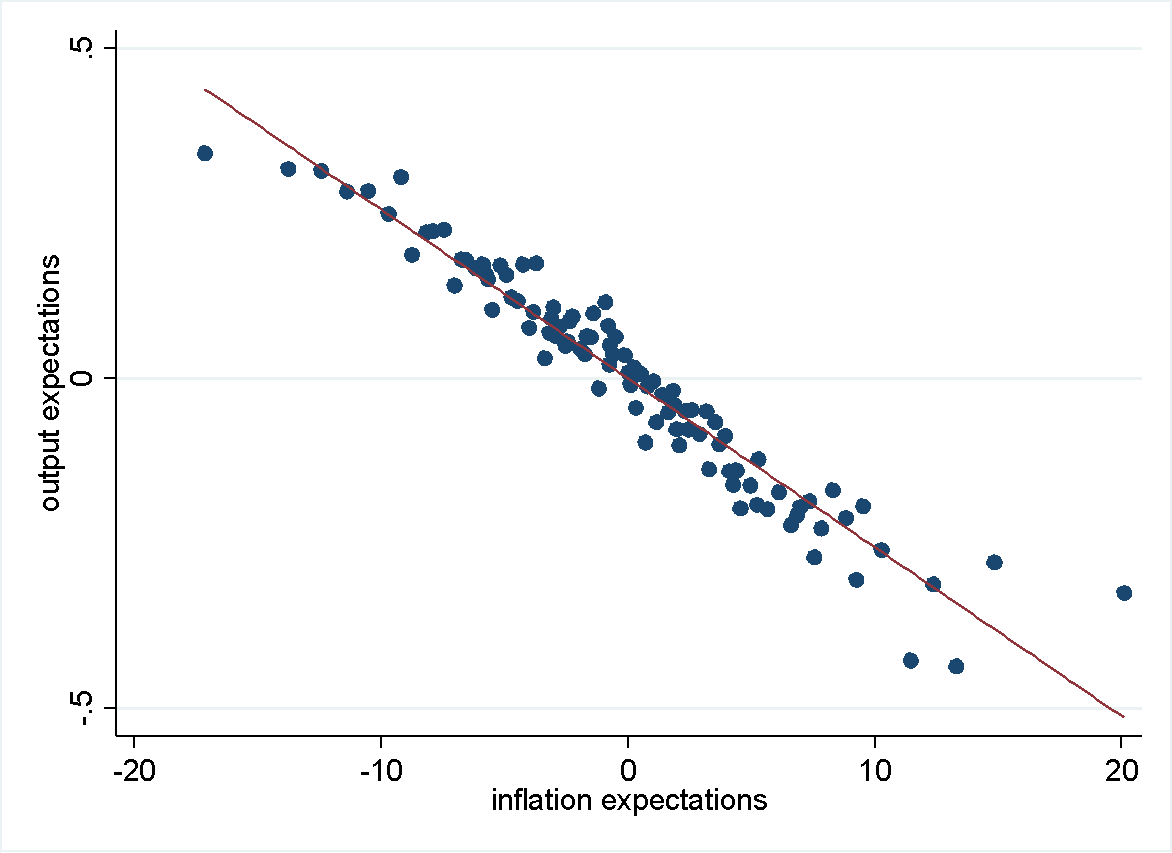

Would increased inflation expectations make managers more positive about their economic outlook? Perhaps, a weaker hryvnia will stimulate exports so much that it is a worthwhile policy? The data clearly show that this interpretation is wrong. Figure 2 demonstrates that managers with higher inflation expectations are more likely to expect a macroeconomic contraction. For every percentage point increase in expected inflation the balance of macroeconomic expectations (approximately, the share of managers expecting an expansion minus the share of managers expecting a contraction) decreases by 2 percentage points, a high sensitivity. In other words, managers interpret high expected inflation as a bad omen and thus are less likely to increase employment or investment.

Figure 2. Joint distribution of expectations for inflation and output.

Notes: the figure plots a binscatter for the joint distribution of expectations for output growth rate and inflation in the next 12 months. For each variable, we take out the time fixed effect and so all variables are mean zero. Inflation expectations are for the-one year ahead horizon. Inflation expectations are reported as answers to multiple choice questions (typically 7-9 options; e.g., the bins could be “less than 5%”, “5 to 10%”, “10 to 15%”, …, “more than 40%”). Output expectations are responses to multiple choice question (“What changes do you expect in the dynamics for output of goods and services in Ukraine over the next 12 months?”) with three options: “increase” (coded as “+1”), “same” (coded as “0”), “decrease” (coded as “-1”). The sample period is 2007-2020.

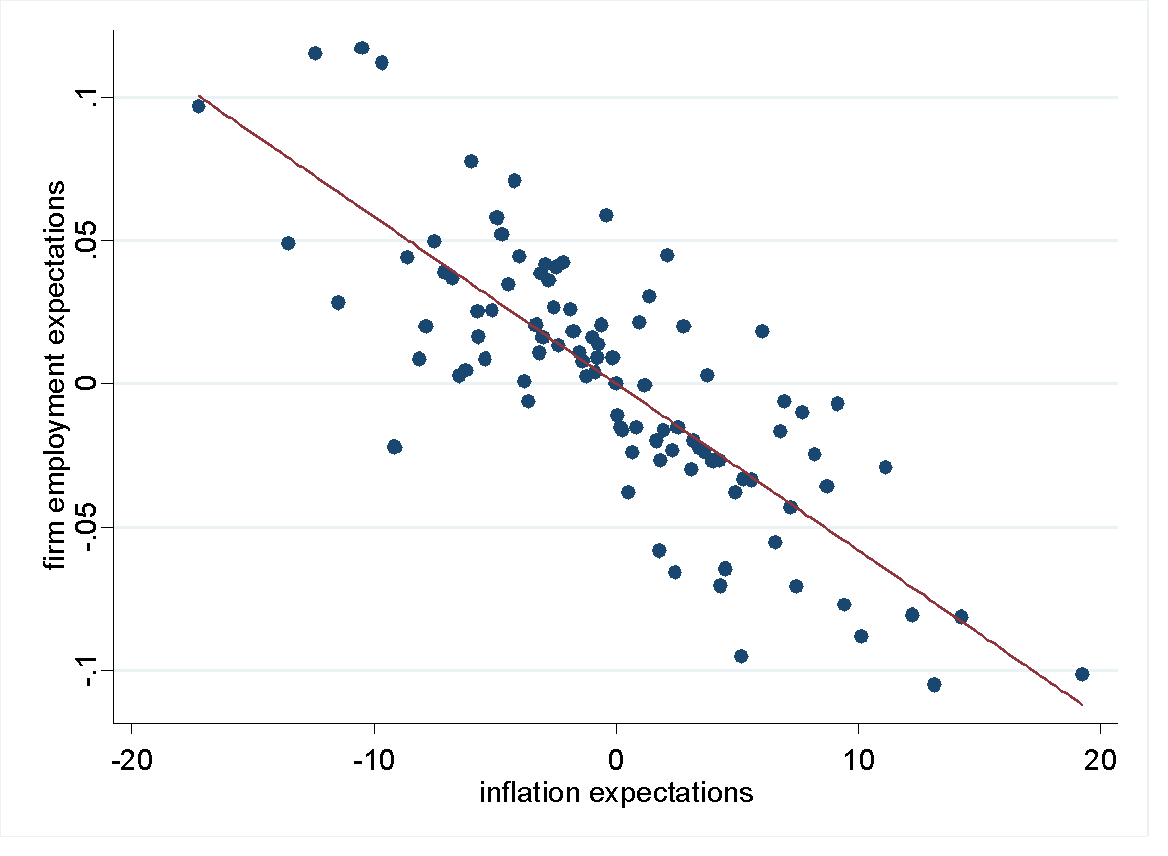

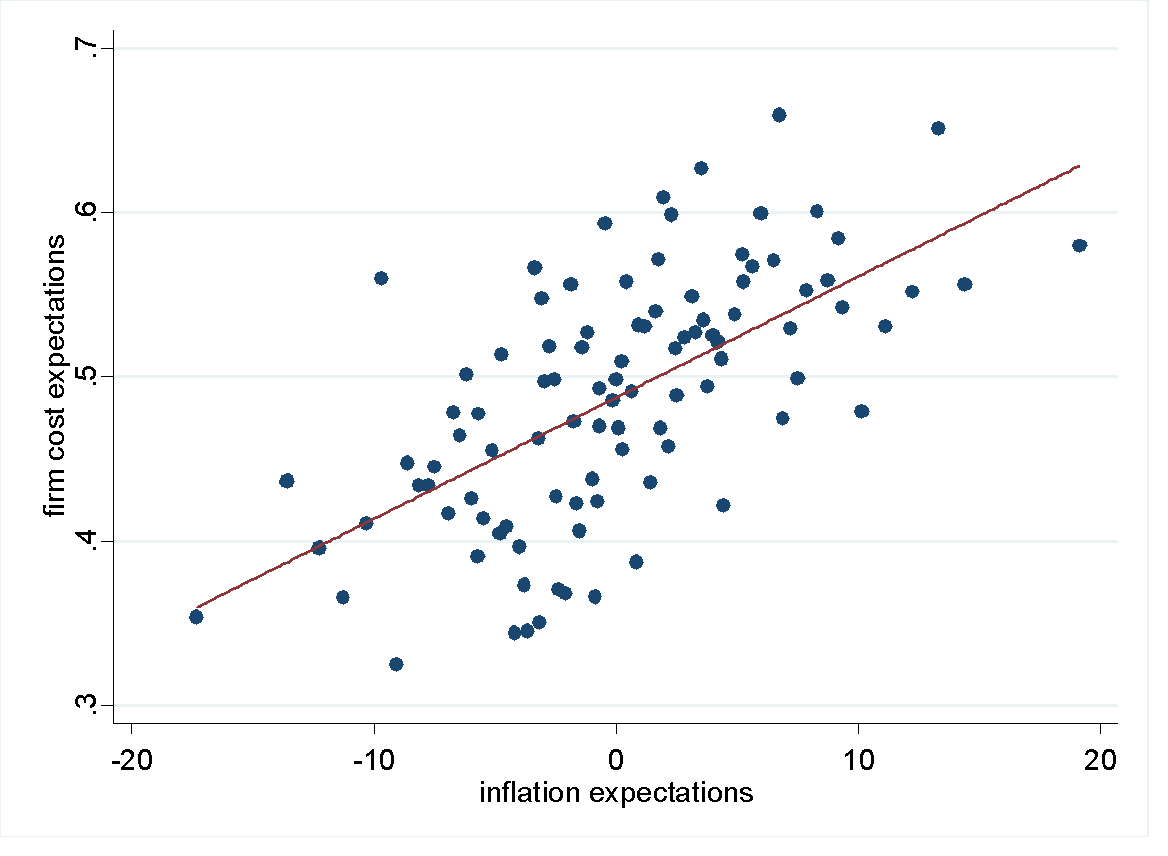

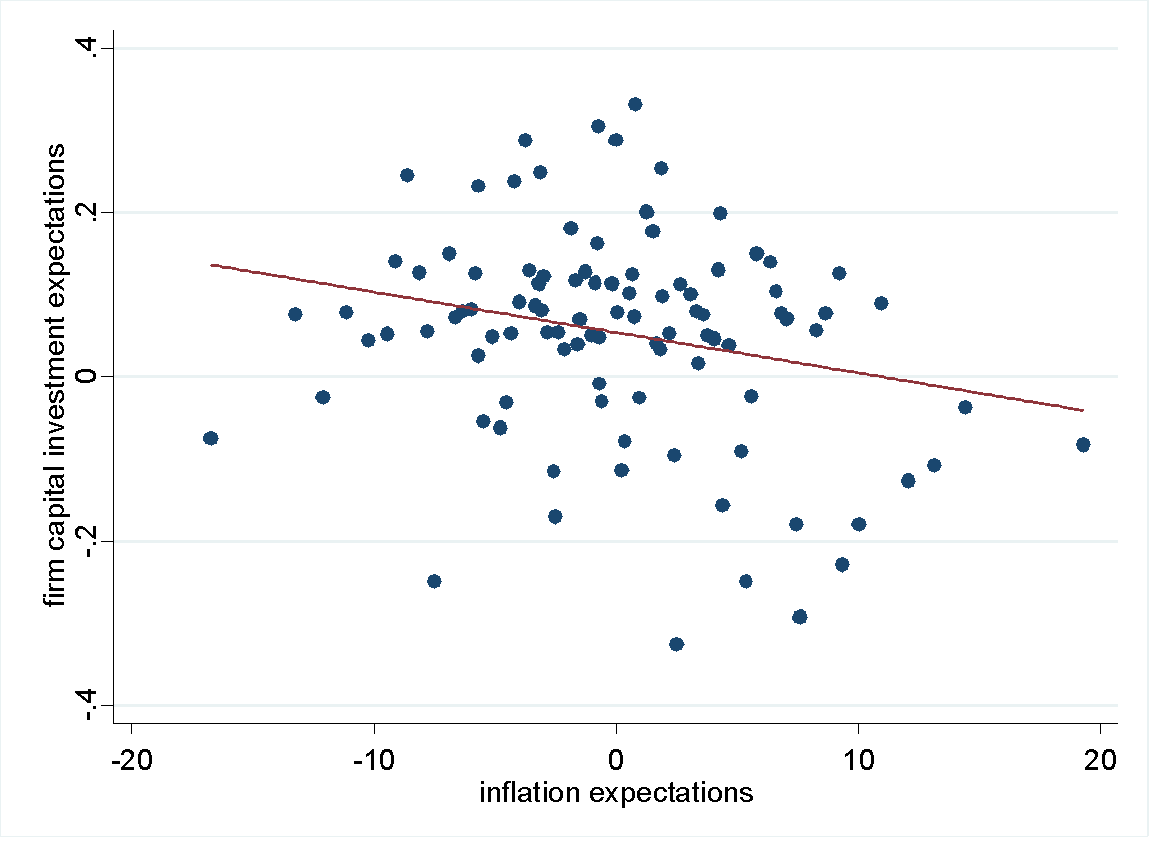

Specifically, consistent with the grim macroeconomic outlook, managers with higher inflation expectations are more likely to expect layoffs rather than hiring and expect higher costs (which means managers are more likely to raise prices). Furthermore, these managers are also more cautious about investment (figure 3). In short, the data do not support the view that raising inflation expectations will stimulate the economy. In fact, the data point in the opposite direction: talks about higher inflation or weaker hryvnia are counterproductive because they can induce a contraction of investment, consumption, and employment.

Figure 3. Joint distribution of expectations for inflation and expectations on firm-level employment, production cost and capital investment

Notes: the figure plots binscatters for the joint distributions of expectations for inflation and firm-level employment, production cost, and capital investment in the next 12 months. For each variable, we take out the time fixed effect and so all variables are mean zero. Inflation expectations are for the-one year ahead horizon. Inflation expectations are reported as answers to multiple choice questions (typically 7-9 options; e.g., the bins could be “less than 5%”, “5 to 10%”, “10 to 15%”, …, “more than 40%”). Employment, production cost, and capital investment expectations are responses to multiple choice questions (“What changes do you expect in the dynamics for employment (production costs, capital investment) over the next 12 months?”) with three options: “increase” (coded as “+1”), “same” (coded as “0”), “decrease” (coded as “-1”). The sample period is 2007-2020.

These simple facts for Ukraine illustrate the perils of poorly-designed policy communication. Igniting inflation fears is easy. Stopping inflation is much harder and costlier. Indeed, the National bank of Ukraine will have to raise interest rates again in the future to contain inflationary pressures thus plunging the economy in a slowdown if not a recession. High interest rates will again launch complaints about high interest rates and the central bank will be pressured to lower interest rates again. This “stop-go” cycle is a hallmark sign of countries with poor institutions. And once a country is in this cycle, it is hard to escape it.

In summary, the choice is very simple: stop interfering with the National Bank of Ukraine, and the inflation will be stable helping the economy to grow. Or continue meddling with monetary policy – and the country will be in a perpetual crisis. What do you choose? “Argentina” or a normal country?

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations