Two years ago, Petro Poroshenko became the president of Ukraine. Many factors indicate that the presidential institution is once again winning the fight against the parliament and the government while continuing to consolidate power. What makes all Ukrainian presidents waste huge amounts of resources trying to subject other branches of power? Does the establishment of personalistic rule once again pose a threat to Ukraine?

It is easy to be pessimistic when looking at the history of independent Ukraine. In the 25 years since the collapse of the USSR, Ukraine has had 17 governments and a couple of significant political crises, while its economy has mostly failed to grow. Moreover, Ukraine has lost part of its territory because of the Russian invasion and is currently fighting a war.

At the same time, 25 years of independent Ukraine offer an inspiring story of freedom-loving and dignified Ukrainians who have continued to struggle against a kleptocratic government. New governments and presidents replace old ones, new influential oligarchic groups emerge. Nevertheless, every time the government crosses the line, Ukrainians storm the streets and take back power.

The recent history of Ukraine is the history of the struggle of Ukrainians against authoritarian regimes. This struggle has not yet produced a clear winner. President and prime ministers, activists and opposition leaders follow in quick succession. Yet 25 years later, Ukraine still has no stable political parties with clear ideologies and lacks national leaders with untainted reputations.

A Vicious Cycle

Political instability in Ukraine has acquired a systemic character.

Yet another political crisis helps new (or not-so-new) forces come to power. President and prime minister balance each other and check the other’s power. Sometimes the struggle comes to a halt after the ruling parties lose support, which helps new forces come to power and starts a new cycle. Sometimes presidents have a puppet prime minister from the very start. Alternatively, they subjects the prime minister in the first several years after coming to power and strengthen their position. Later, strong presidents may evolve into an authoritarian leader. Their actions cause yet another Maidan and the reshuffle of the ruling political forces after long protests.

An observer can note that the danger of a strong president’s is still very real. Many factors indicate that, in Ukraine, the presidential institution has once again won its struggle against the parliament and the prime-minister/government and is continuing to consolidate power.

Topic of the week: The institution of the Presidency

What It Take to Pass a Law – a View From the Data (Dmytro Ostapchuk, VoxData Editor)

Petro Poroshenko`s Political Life (Anton Marchuk, student of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv)

In December and January, many ministers of the previous government announced their resignations. The resignation of the Minister of Economy Aivaras Abromavicius had the largest impact, as he accused the President’s entourage of exerting undue pressure. This political crisis lasted the whole winter. It resulted in the slowdown of reforms and non-compliance with the IMF program’s conditions, and as a result, a further delay in the delivery of the IMF tranche.

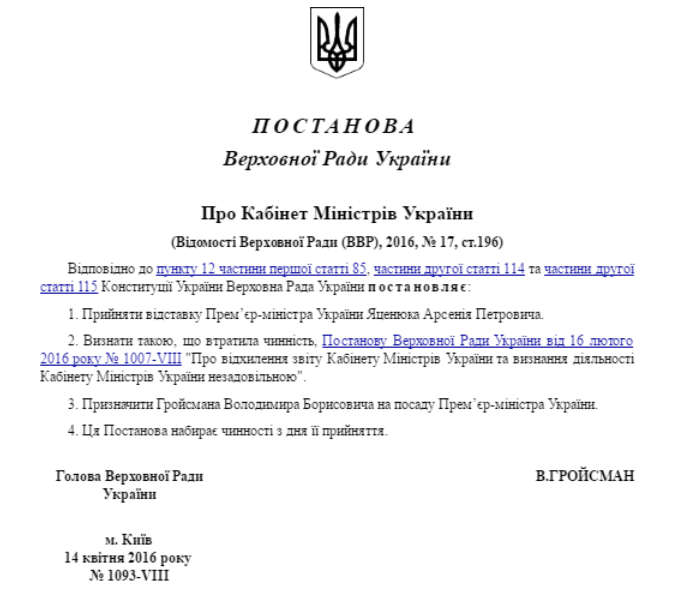

On April 14, Volodymyr Groysman, deemed by many to be more loyal to the President than Arseniy Yatsenyuk, was appointed as the new Prime Minister.

Interestingly, the appointment of the new Prime Minister was accompanied by numerous grave violations of law. This is important because such violations illustrate the diminishing importance of rules and the breakdown of the system of checks and balances. In particular, we witnessed the unusual legislative confirmation of the existence of a political agreement in the form of the Resolution №4423. This resolution directly contradicts the constitution, several laws (on the Parliament’s procedures and on the government, first of all), as well as the logic of the premier-presidential model in Ukraine. The mutual distrust of all sides resulted in the inclusion in one document of numerous decisions that could all have been made legally through separate and quite different procedures.

- For instance, new ministers and the Prime Minister were appointed with no formally registered coalition in place (with no list of all member MPs). Only such a coalition could have had the right to propose the names of ministers to the president (except the ministers in the presidential quota). Yet the aforementioned resolution was supported only by two fractions that did not have a majority in the parliament. This is a violation of par. 3 of Article 114 of the Constitution.

- The resolution violates the right of the President to submit a nominee for the position of the Prime Minister to Parliament (par. 2. Article 114 of the Constitution).

- Another violation is the simultaneous inclusion in one document of the decision to dismiss the Prime Minister, appoint another Prime Minister and ministers from the presidential quota (Articles 14 and 115 of the Constitution).

- Other curious decisions include the appointment of incumbent ministers of the previous government as new ministers without first dismissing them, as well as the cancellation of the negative assessment of Yatsenyuk’s government.

You can find the complete analysis of all the illegal aspects of Resolution №4423 here.

Full House

On May 12, Parliament consented to the appointment of Yuriy Lutsenko, the former head of the presidential fraction, as the third post-Maidan Prosecutor General. Earlier, Parliament approved legislative changes that paved the way for Lutsenko. Besides, Parliament illegally ignored an alternative draft law proposed by the opposition. The pro-presidential law was instead adopted and published immediately.

Finally, Parliament has recently passed laws that strengthen the control the President has over judges (for a transition period, which accidentally ends at the time of the next presidential election in Ukraine).

Therefore, the President’s control over the judicial and executive branches is rising steadily. New anti-corruption agencies in the “presidential vertical” have not demonstrated any results in the struggle against corruption so far. Yet they can already be an effective tool of control over financial and political elites. Local authorities, despite the promises given during Euromaidan, have not become a counterweight to the almighty Center. The current weakness of Parliament with its extremely loyal (to the President) speaker, nameless coalition and divided opposition removes the only national legitimate counterweight to the presidency. Unfortunately, it is now possible to argue that the restoration of the parliamentary-presidential system, which happened on February 21-22, 2014 after the Euromaidan’s victory, is no longer valid.

Lottery

Certainly, the consolidation of power by the President does not necessarily mean that this power is going to be used contrary to the public interest. At the same time, if Parliament is no longer able to check the President’s power, there are no guarantees and constraints against the possible use of power for his own benefit or by interest groups.

Unfortunately, the history of independent Ukraine shows that its presidential institution has been one of the main sources of threats to the freedoms and dignity of citizens. The power of oligarchic clans of the past and current financial-political groups lies in the conditional support they give to presidential authoritarianism. Together, the formal presidential institution and informal financial-political groups easily subject the judicial, executive, and legislative branches of power and merge them into a single vertical, using them for their own benefit and not in the public interest.

In post-Soviet countries, it is from the presidency that the authoritarian threat emerges time and time again. The office of the president was invented at the end of the Soviet era in order to free the head of the state from the control by the Politburo and Central Party Committee. After the USSR collapsed, the presidency has developed its authoritarian element in the struggle against other political institutions. Therefore, even the most democratic presidents have become champions of autocratic rule after spending 1.5–2 years on this Procrustean throne.

This danger is very real now. A national debate should start on how to minimize the risk of authoritarian revanche and how to use the consolidated power with the aim of transforming, modernizing and democratizing Ukraine.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations