Women’s economic activity is a prerequisite for gender equality. A woman who works gains more financial autonomy and the ability to make decisions independently, thus wielding greater influence in political and social processes. Moreover, women’s participation in the labor market positively impacts the economic development of a country. According to the McKinsey Global Institute in 2015, if women were equally engaged in the labor market as men, global GDP would increase by 26% by 2025. Unfortunately, today, women’s participation in the global labor force stands at only 50%, compared to 80% among men.

At the same time, women’s employment is negatively associated with the fertility rate (Behrman, 2022). While the birth of a child has almost no impact on men’s employment, 40% of women in European countries state that having children affects their careers. After the second child, 47% of women reduce their working hours; after the third, 70% leave their jobs (Pailhé, 2006). Therefore, a woman’s decision to have a second or third child is potentially a choice that significantly complicates career advancement.

To enable women to both pursue their careers and have children, appropriate family policies supporting the harmonious balance between work and childcare are essential. Among the most common are caregiving support policies. Table 1 examines factors contributing to increased economic activity among women and planned policies aimed at increasing birth rates in Ukraine’s Demographic Strategy. The good news is that the latter largely aligns with the former.

Table 1. Comparison of factors contributing to economic activity and policies promoting birth rates

| Factors contributing to the increased economic activity of women | Proposals for policies to increase birth rates from Ukraine’s Demographic Development Strategy |

| Availability and accessibility of full-day childcare centers; availability of nurseries for children aged 1-3 years (Christiansen, 2016, Ünver, 2018). |

|

| Promotion of flexible work schedule practices; opportunities for remote work (Magda & Lipowska, 2021; Maraziotis, 2024) | Promoting successful practices of employees with children working in flexible and remote modes. |

| Childcare leaves should not exceed one and a half years (Duvander, 2011, Rønsen & Sundström, 2002, Ruhm, 1998, Kunze, 2022, Lalive&Zweimüller, 2009, Ejrnæs & Kunze, 2013). It is crucial to have a well-developed system of childcare facilities to enable mothers to return to work. | |

| Setting part of paid parental leave for fathers only (Andersen, 2018, Johansson, 2010, Dunatchik, 2020). | Introducing a practice (and quotas) mandating fathers to use a portion of parental leave. |

| Promotion of ideas for equal distribution of caregiving and household work between men and women (OECD, 2014, UNECE – UN Women, 2021 ) | Promoting the involvement of fathers in childcare and an equal distribution of family responsibilities. |

| Encouraging women’s participation in high-paying and in-demand professions, particularly in STEM fields (WomenTech). | Promoting among women training programs aimed at mastering entrepreneurship fundamentals, competitive professions, and skill enhancement. |

| Consultative support for women returning from childcare leave (Rubuļņika, 2022). | |

| Life factors: absence of a partner, single parenting, or low partner earnings (Stähli et al., 2008, Yang, 2021, Albanesi & Prados, 2022). | Developing grant programs for opening/developing businesses by women, particularly single mothers. |

| Consultative and financial support for women entrepreneurs (European Investment Bank, 2022). | |

| Cultural orientations and gender stereotypes prevalent in society (Jensen, 2017). | Developing and implementing informational campaigns to promote the model of families with two or more children. |

Source of the table: Compiled by the author from open sources.

A large number of empirical studies in OECD countries provide evidence on the effectiveness of policies for the provision of childcare services (kindergartens, crèches, etc.). However, such services must meet several criteria: sufficient availability, financial and territorial accessibility, and the quality of education in preschool institutions (Ünver, 2018). According to research, one-time payments have a significant but short-term positive impact on fertility and a negative impact on women’s employment.

Noteworthy also is the design of parental leave policies. Research demonstrates that after taking leave longer than 12-16 months, women have fewer chances for career advancement upon returning to work (Duvander, 2011, Rønsen & Sundström, 2002, Ruhm, 1998). Conversely, parental leave shorter than a year positively impacts return to work and does not diminish mothers’ career prospects (Kunze, 2022, Lalive&Zweimüller, 2009). Germany’s experience is illustrative, where parental leave gradually extended from 7.5 to 37.5 months during 1985-1995, negatively affecting mothers’ wages and their likelihood of returning to full-time work (Ejrnæs & Kunze, 2013). In Austria, extending leave from one to two years in 1990 significantly reduced the percentage of women returning to work (Lalive&Zweimüller, 2009).

The average duration of parental leave in OECD countries is 67.5 weeks, approximately 14 months. Potential reasons for the negative impact of lengthy leave include women maximizing its duration, thereby delaying their return to work. Prolonged absence from work can lead to the loss of specific skills or the inability to acquire skills obtained by colleagues. Consequently, a woman’s competitiveness within the team diminishes, and reintegration into the work context becomes more challenging. Conversely, shorter leaves need to be supplemented with policies that provide access to high-quality childcare services, such as kindergartens. In the absence of such services and with short leave periods, some women may be compelled to quit their jobs to care for their children independently.

Important for gender equality are policies that promote a more equal distribution of unpaid work between men and women. According to global data, women spend, on average, 2.8 hours more per day on caregiving and household chores compared to men. The expectations placed on women to bear and raise children while also participating in the workforce create a “double burden” (Van Corp, 2013). One of the policies addressing this issue is “quotas” for fathers during parental leave. Such leave is most common in Scandinavian countries, where 1-3 months of paid parental leave are specifically designated for fathers. If fathers do not take this leave, it cannot be transferred to another caregiver, resulting in its loss. Evaluations of these policies in Sweden and Denmark have shown a positive effect on mothers’ wages, reducing the “motherhood penalty” (Andersen, 2018, Johansson, 2010). In Quebec, Canada, similar policies have led to a five percentage point increase in the likelihood of women returning to full-time work (Dunatchik, 2020).

In the context of women’s employment, it is essential to consider gender segregation both vertically (representation of women in leadership positions) and horizontally (employment of women across different sectors). For example, there are more men in managerial positions in the industrial sector and more women in the education sector. Among the policies addressing vertical segregation, corporate quotas for women in top positions are widely adopted. In 2022, the European Union adopted a Directive requiring companies to have a minimum of 40% women on non-executive boards by 2026. Reducing horizontal segregation involves initiatives such as quotas for girls pursuing careers in STEM fields, developing qualification programs for women entering traditionally male-dominated professions like carpentry, electrical work, and driving, and promoting such female role models.

In our opinion, obtaining a profession in a highly paid field typically dominated by men may incentivize women to return to work sooner after maternity leave. Employers may also seek to retain valuable female employees by offering them flexible work schedules.

The number of hours of paid work performed by women often significantly differs from that among men. Women more frequently work part-time, which, on the one hand, allows them to balance family and work responsibilities. On the other hand, it often does not provide them with sufficient earnings to ensure economic independence and reduces chances for career advancement. The idea of reducing the overall working hours is gaining popularity, which could help in combining work and family responsibilities, but it remains challenging to implement. Currently, the most widespread practice is promoting flexible and remote work arrangements. It would be beneficial to offer the option of flexible working hours to men as well. This would allow for a more equitable distribution of family responsibilities between partners. However, it is necessary to analyze whether such an approach might lead to a decrease in income for all families with children compared to those without children.

Finally, gender stereotypes and societal attitudes toward working mothers can significantly influence the outcomes of implemented policies. For instance, in some cities in Western Europe, despite having full coverage of childcare facilities, women’s economic activity remains low. Conversely, in other cities with low childcare provision, more women are employed (Jensen, 2017). If a country has established norms that dictate mothers should primarily care for children while fathers are the primary breadwinners, implementing policies aimed at gender equality should be accompanied by active efforts to change cultural beliefs.

What about women’s economic activity in Ukraine?

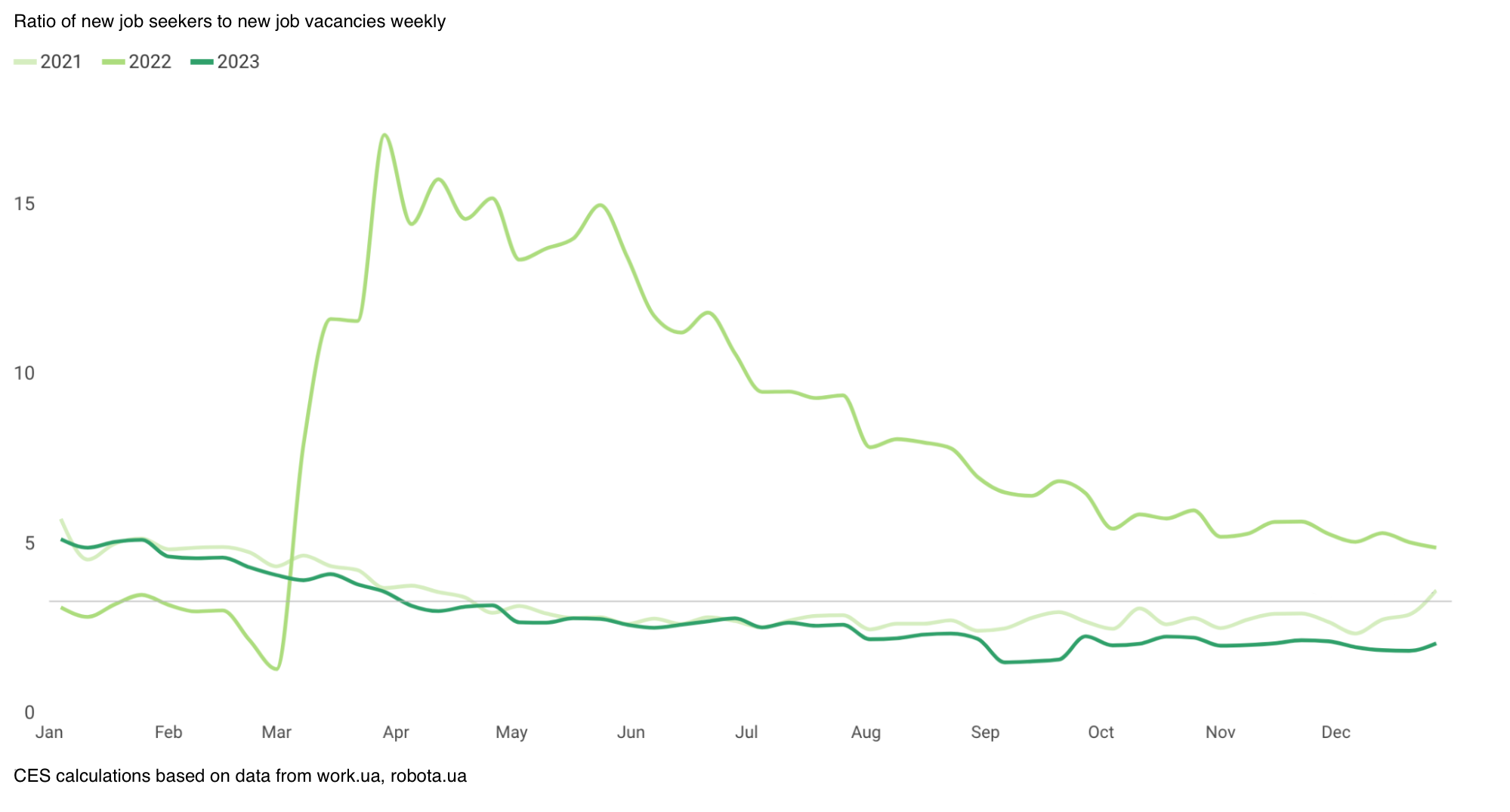

According to calculations by the Center for Economic Strategy (CES), the labor market in Ukraine has been gradually recovering since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, and the number of vacancies increases. In February 2023, the number of open vacancies reached 60% of the pre-war period, which, according to Work.ua, marked the peak of labor market recovery. However, there are not as many responses to job openings, and according to an NBU survey, 25.6% of employers have difficulty finding qualified workers. Statistics from Work.ua for June 2024 show that the ratio of open vacancies to resumes has nearly equalized — 64,000 and 79,000, respectively. The shortage of personnel is exacerbated by the loss of population due to Russia’s aggressive actions — occupation and deportation from the occupied territories, migration of 5.9 million people abroad, of whom 80% are women and children, and mobilization for the Defense Forces. Official estimates indicate that Ukraine’s population decreased by 5.7 million in 2023 compared to 2022, totaling 36.3 million people, while on territories under Ukrainian control, it amounted to only 31.5 million people.

Figure 1. Ratio of new job seekers to new job vacancies in 2021-2023

Source: Center for Economic Strategy

In 2021, the economic activity rate of women aged 15 and above in Ukraine was 47.8%, whereas, for men, it was 62.9%, indicating a 15 percentage point difference favoring men (estimated by the IOM methodology).

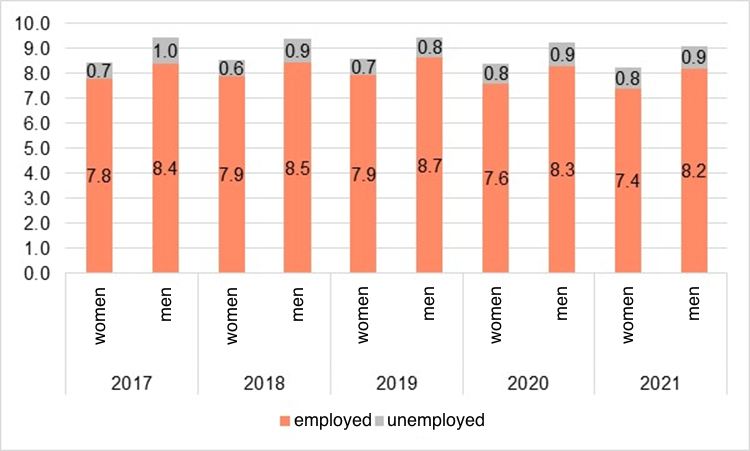

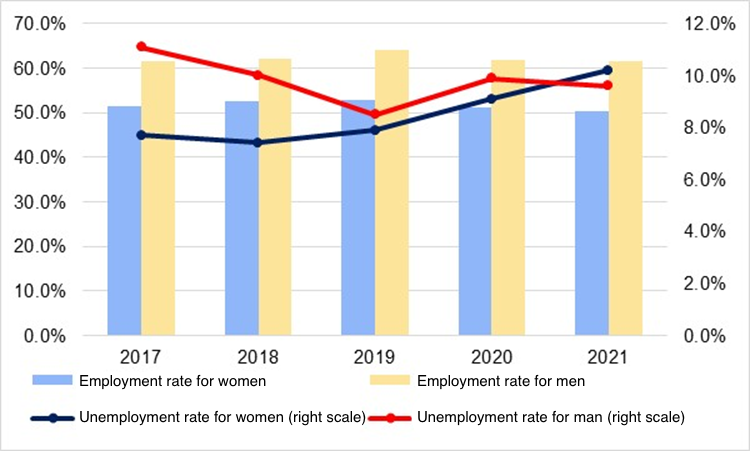

Over the 5-year period from 2017 to 2021, the unemployment rate among women aged 15-70 increased by 2.5 percentage points, likely influenced by the pandemic, while among men, it decreased by 1.5 percentage points (see Figure 2). In 2022, the proportion of employed women increased by 1%, attributed to the outflow of male workers and subsequent changes in the workforce structure at enterprises. Research on the labor market in 2022-2023 highlighted successful cases of retraining female personnel as welders, drivers, and forklift operators to fill positions previously held by men.

Figure 2. Labor market in Ukraine from 2017 to 2021 from a gender perspective: Employment and unemployment in millions of people, and (b) Employment and unemployment rates

(a)

(b)

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine

Note: Employment rate as a percentage of the population aged 15-70 years, unemployment rate as a percentage of the labor force aged 15-70 years.

Women’s participation in the labor market varies by sector. In 2021, women constituted a minority (28-35%) among workers in agriculture, industry, transportation, and warehousing, while they predominated (75-85%) in sectors such as postal and courier activities, healthcare, education, and the operation of libraries, archives, and other cultural institutions. Their share across sectors has not significantly changed since 2015.

Figure 3. Share of women in the average number of workers by economic sectors, %

However, regardless of the economic sector, women earn less than men except in the administrative and support services sector, where the wage level is nearly equal. This difference may be due to vertical segregation (men more often occupy managerial positions), horizontal segregation (if certain jobs are better paid and men more frequently hold these positions), or the "motherhood penalty" — lost career opportunities due to time out of the labor market for childbirth and childcare. This issue requires further detailed research so that Ukraine can direct policies to address the reasons why women earn less than men.

Figure 4. Average monthly wages by sectors of economic activity, men and women, 2021

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Note: The orange represents women, and the blue represents men.

The Center for Economic Strategy conducted a study in 2019 and found that the main reasons for women's unemployment in Ukraine are the desire to take care of the children on their own (28%) and the lack of alternative childcare options such as kindergartens, nannies, or relatives (29%). The Demographic Development Strategy also mentions the issue of insufficient childcare services. According to the Strategy, this problem leads to a significant difference in the employment rates of women with young children (aged 3-5 years) compared to women without children, specifically 71.1% employment without children versus 51.5% with children. Today, this problem has been exacerbated due to the lack of available shelters in many kindergartens.

Practices to increase women's economic activity in other countries

The structure of the economy in Ukraine is predominantly services-oriented, and the birth rate is low, similar to that of developed countries. Therefore, for comparison, we primarily selected European countries. Additionally, we considered Israel due to its experience with ongoing conflict.

Figure 5. Fertility rate versus female labor force participation, 2021

Source: Our World in Data

In Sweden, the share of economically active women in 2023 is 63.4%, and the fertility rate is 1.67. These are relatively high indicators compared to the OECD average, where women's economic activity reaches 53.21%, and the fertility rate is 1.56. Globally, these figures are 50.54% and 2.26 respectively (indicating that fertility rates in OECD countries are lower on average than in the rest of the world). Among the most effective policies associated with these relatively high fertility and female labor force participation rates are the availability of early childhood education facilities, gender-neutral parental leave with "daddy quotas," and flexible work schedules.

Since 1970, Sweden's daycare and preschool education system has been actively developing. Today, all children aged 1 to 5 have the right to preschool education, and children aged three and above are entitled to at least 15 hours per week of free (subsidized) preschool education if their parents are not working or are on parental leave. Municipal preschools operate from 6 a.m. to 6:30 p.m., and every city has several facilities that operate around the clock. There is also an educational care service, which can be provided at the teacher's home. Parents with insufficient income have the right to free preschool education for their children. In 2019, half of one-year-old children attended preschools, and this percentage was 90.6% for two-year-old children. The cost of childcare in such facilities is a maximum of 3% of the parents' income. The cost is cheaper for the second or third child and free for the fourth child. Each group in the preschool can have up to 16 children, with a staff-to-child ratio of 1:5.2 as per regulations.

Parental leave for childcare amounts to 480 days. These days are divided between partners by mutual agreement, but each must take at least three months out of the total leave. It is impossible to transfer these days to the other person; if one partner cannot or does not want to use their allocated three months, those days are forfeited. Women can start using this leave 60 days before childbirth. During the first 390 days (approximately 13 months) of parental leave, parents receive 80% of their previous salary. After this period, they receive around 15 euros per day.

In 2022, Sweden reformed its labor legislation, introducing full-time employment by default and part-time employment by agreement. They allowed the reduction of working hours for employees with standard duties and mandated the transition of employees who have worked on fixed-term contracts for one year to permanent contracts, among other measures. Some experts argue that from a gender equality perspective, such an approach helps women avoid falling into the "part-time work trap," facilitates their return from parental leave to full-time employment sooner, and balances their career opportunities with men.

In Austria, the program "Karenz und Wiedereinstieg" provides consultation to parents regarding parental leave and opportunities for professional training and reintegration into the workforce after leave. Participants in the program can receive financial support of up to 4000 euros for training in new professions.

Support programs during job searches and computer literacy courses are offered for women who have been unemployed for an extended period or are aged 50+. Additionally, transitional employment programs provide job placements for up to 6 months in social enterprises. These programs are funded by the state budget to help marginalized population groups gain work experience and facilitate their job search in the market. The Employment Center's "Eingliederungshilfe" program serves a similar purpose by providing female employees with minimum wage subsidies for three months if they secure employment in the open labor market. This initiative assists women in returning to work while allowing employers to evaluate female candidates using funds from the Employment Center and make decisions regarding their further employment.

Under the Job PLUS Ausbildung program, participants can undergo training consisting of both theoretical components and practical experience at an employer's premises. During this training, participants receive a modest salary and have the opportunity to understand how suitable their chosen profession is for them while already being in a workplace setting. These programs are financed by the Employment Center, and the training directions are determined based on the needs of the labor market. A similar program called FiT helps women acquire technical and manual professions such as electricians, locksmiths, mechanics, etc. During their participation in such a program, women receive professional orientation, internship opportunities, vocational training, and financial support.

In Germany, a program called Perspektive Wiedereinstieg provides individual counseling and group sessions for those returning to work after parental leave. The program organizers seek out supportive employers and assist participants in finding employment.

In Israel, the economic activity rate among women was 60.9% in 2023, compared to 68.8% among men. In 1991, the economic activity rate for women was 46.8%, indicating a growth of 14 percentage points over 30 years. The fertility rate in Israel is 2.9, significantly higher than the OECD average. However, this rate varies among secular women (2.1), ultra-Orthodox women (6.5), and Muslim women (3.6). Policies supporting both fertility and women's employment include state-funded in vitro fertilization, job protection policies during pregnancy, fully paid maternity leave, subsidized childcare services, and free preschool education. Additionally, there are provisions for reduced working hours upon return from maternity leave.

Maternity leave and childcare leave are combined into a single 26-week (182-day) leave. The first 15 weeks (105 days) are fully paid at 100% of the previous salary. The subsequent 14 weeks are unpaid, but the mother retains her job during this period. In 2014, approximately 60% of women returned to work after completing the paid leave. The leave can be transferred to the father under certain conditions, though in 2016, only 520 fathers utilized this option, which is less than 1% of those eligible. Reasons cited include the short duration of the leave, which makes splitting it impractical, and the lack of financial incentives for fathers to take such leave. Since 2016, fathers have also had the right to five days of paid leave following childbirth as part of their annual leave entitlement.

The "Parenting Hour" policy allows fathers and mothers to leave work one hour earlier for up to four months following the birth of their child. Their wages are maintained despite the reduced working hours. This option is available to parents who work full-time jobs requiring a minimum of 43.5 working hours per week (the "standard" workweek in Israel is 42 hours).

Since 2011, the state has subsidized 90% of the cost of preschool education for children older than three years. However, childcare for children aged 0-3 years, for example, was only covered by the state at 15% in 2015. Childcare for children aged three months to 3 years is mainly offered by daycare centers and family daycares, where childcare is provided at the caregiver's home for up to 5 children per group. The state recognizes these family daycares, considering the shortage of other options and their relative affordability.

The Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs maintains a registry of recognized family daycares. Parents have the right to subsidize their children's attendance in such daycares or centers, depending on their income level and the number of children. These subsidies can cover up to 45% of the daycare costs. However, as of 2017, only a quarter of the children attending these facilities received these subsidies, indicating that the demand for such services exceeds the availability. To address this shortfall, in 2016, 4.7% of children under three years old were cared for by nannies, 21.5% by mothers, 13.2% by other family members, and 28% attended private childcare facilities not subsidized by the state.

In 2017, the Extended Day Program "Nitzanim" was introduced to synchronize parents' working hours with preschool education facilities for children aged three and older. This program is subsidized by the government and allows children to stay in preschool facilities until 4:00-5:00 p.m. The program has two options, with one operating on school days off, offering longer hours and more activities. The type of program provided is determined by the local authorities, with wealthier communities typically able to afford more comprehensive options.

Working parents of children under five also receive tax benefits calculated using tax points. Each tax point in 2024 equaled approximately 60 euros. When a child is born, parents receive 2.5 tax points. As the child reaches one and two years old, parents receive 4.5 tax points; at three years old, they receive 3.5 points; and at four and five years old, they receive 2.5 points each. Additionally, parents who earn modest incomes can qualify for a "work grant," which is a state subsidy aimed at encouraging parents to remain active in the labor market.

Policies related to women's economic activity in Ukraine

In 2023, the Ukrainian government approved the National Strategy for Bridging the Gender Pay Gap, aiming to reduce the gap from 18.6% to 13.6% by 2030. The Strategy for Gender Equality in Education until 2030 was also endorsed. When developing policies to implement these strategies, Ukraine aligns with the Council of Europe Gender Equality Strategy for 2024-2029. Policies related to women's economic activity primarily concern maternity leave, childcare services, entrepreneurship support programs, and more.

Ukrainian women and men have the right to several leaves that help balance family and work.

Leave in connection with pregnancy and childbirth is a paid leave provided to women for 126 days. The leave can be taken from the 30th week of pregnancy onwards and is granted in full regardless of how much time remains before childbirth. Payments during maternity leave are based on 100% of the woman's income from the previous year. From 2023 onward, part of the leave allocated before childbirth can be used partially or in full after childbirth. This means that if there are no medical contraindications, a woman can work up until childbirth and receive 126 days of paid leave afterward.

Leave for childcare until the child reaches three years of age has also been available to fathers since 2021, following the completion of maternity leave after pregnancy and childbirth. This leave continues until the child turns three and is unpaid. However, Ukrainian families receive assistance upon the birth of a child amounting to UAH 41,280 (UAH 10,320 as a one-time payment and the rest in equal installments over the next 36 months, approximately UAH 860 per month). The time spent on such leave counts towards the insurance period for pension purposes. From 2021 onward, it is allowed to work from home or on reduced working hours during this leave.

Leave in connection with childbirth: Since 2021, fathers or other caregivers who are close relatives of the child have the right to take 14 days of additional paid leave for childcare in addition to the main parental leave. This leave can be taken no later than three months from the day of the child's birth. Its purpose is to involve fathers in caregiving and to support primary caregivers, predominantly mothers, after childbirth.

If a caregiver needs to care for a sick child up to 14 years old, they can receive financial assistance for up to 14 days upon providing a doctor's certificate. The amount of the aid ranges from 50% to 100% of the salary, depending on the person's pensionable service.

Compensation under the "Municipal Nanny" program for those raising a child under three years old with a disability or severe illness or who themselves have a disability equals the minimum wage, which in 2024 is UAH 8,000.

In Ukraine, the number of kindergartens decreased from 24,500 in 1990 to 14,800. Coverage for children aged 3-6 years is 53%, whereas in Europe, it reaches 82.5%. In rural areas, 35% of children attend kindergartens, compared to 62% in cities. Coverage for children under three years old is significantly lower. For example, in recent years, on average, only about 30 children under the age of 1 have been enrolled in preschool education institutions each year. The issue lies not in parents' unwillingness to send their children to kindergartens but rather in the shortage of kindergarten places. Although waiting lists for kindergartens slightly decreased from 2012 to 2019, this might be due to exceeding the norm (maximum of 20 children per group aged 3-7 years, 15 children aged 1-3 years, and 10 children under one year old) or because parents found alternative care options.

Parents wishing to enroll their child in a kindergarten can register in an electronic queue and monitor its progress online. The minimum age for enrollment in a kindergarten is 1.5 years. Attendance in municipal kindergartens is free, except for meal payments, which are often subsidized, and children from privileged categories receive free meals.

The government program "Own Business" offers grants for starting or expanding a business up to UAH 250,000. The program began in 2022, and 8,000 women have received financial support since its launch. Overall, 56% of the program's grantees are women, indicating a strong interest among women in starting their own businesses and a demand for this type of assistance. On the Diia portal, various online educational resources are available to women entrepreneurs.

At the same time, Ukraine lacks consistent programs to support women's entrepreneurship across all regions. Specifically, there are no programs supporting single mothers who wish to start or develop their businesses. In 2021, Ukraine had 969,000 families without one or both parents, with 96% of them being single mothers. Under war conditions, this number is expected to increase. Single mothers often bear the "double burden" of paid and domestic work as work is a matter of survival for them.

The most common practices to encourage women's employment among Ukrainian companies include retraining programs, female leadership initiatives, and creating spaces for children. For example, StarlightMedia has set up a children's playground and a family area in their office, allowing parents of young children to bring them to work as needed. This space includes a play zone, a place for children's meals, changing facilities, and workstations for parents. MHP company also has a children's room in its office. Additionally, they have experience retraining female employees for positions such as truck drivers, traditionally considered male-dominated professions. Intellias has equipped its offices with children's rooms and supports a Leadership School for women employees. Projector Institute has launched a program to train women in IT skills, offering scholarships for education. Since 2017, Astarta has been supporting the "ІТ-Education in Rural Areas" project, which is accessible to women as well. More examples of Ukrainian businesses supporting working women can be found in the UN Women Handbook.

What else can Ukraine do?

The Demographic Strategy project proposes solutions that do not contradict women's economic activity and have the potential to simultaneously increase both birth rates and women's employment (see Table 1). Since childcare services are one of the most important factors enabling mothers to enter the workforce, it is crucial to detail the strategy's goals regarding this aspect. In addition to the financial and geographical accessibility of childcare services, it is critical to have the possibility to access these services until the end of the working day and to have nursery groups for children up to three years old.

Another positive aspect of the strategy is its focus on acquiring competitive professions, often considered "male-dominated." Training girls in technical occupations and facilitating their first experience in these fields before childbirth will increase their chances of returning to these professions. This approach includes financial incentives and employer readiness to adapt to the needs of highly skilled female workers.

International experience shows that paid parental leave lasting up to 1-1.5 years in addition to childcare facilities is most favorable for working women. This policy encourages mothers to return to work and remain competitive because, during this period, women are less likely to lose important skills, making it easier for them to reintegrate into the workforce. Various countries also implement flexible work schedules. For example, Austria and Israel see this as a positive incentive for balancing family and work duties, while Scandinavian countries advocate for full-time employment for women, thereby enhancing their competitiveness in career opportunities alongside men. Targeted programs such as job search counseling, mentoring, and support for women in business, which are stable and accessible to most women, are important policies that Ukraine can adopt.

Improving the quality and accessibility of childcare services, especially for children up to 3 years old

In March 2023, Parliament adopted as a basis a bill on preschool education. The bill proposes improving the territorial accessibility of preschool institutions and reducing queues for kindergartens. A significant change that could affect women's economic activity is opening nursery groups for children aged three months to three years. The availability of early childhood care can allow women to avoid prolonged maternity leaves and return to work relatively quickly without losing career opportunities.

Increasing fathers' involvement in caregiving tasks

Following the example of Scandinavian countries and in accordance with the EU Directive on work-life balance for parents and carers, it is recommended that at least two months of paternity leave be introduced exclusively to fathers. Such leave can encourage fathers to participate more in caregiving responsibilities. However, considering that a significant number of men are currently defending Ukraine due to war conditions, this proposal would be more appropriate for the post-war period.

Implementing counseling and job search assistance programs for women reentering the workforce

Such programs could be provided not only by the Employment Center but also by recruiting agencies with appropriate funding. These programs should include career counseling and coaching services, market orientation activities, workshops for developing soft skills, and networking opportunities with potential and supportive employers.

Implementing programs to encourage women to pursue careers and gain experience in high-paying and high-demand fields

According to the Ministry of Economy forecasts, the demand for professionals in the information and telecommunications sector is expected to grow by 2.2 times by 2028 compared to 2022. There will also be increased demand for engineers, technical specialists, STEM professionals, and energy experts. These fields in Ukraine offer the highest salaries but currently have a gender bias in favor of men already from the stage of professional training. In order to ensure women have opportunities to develop in these sectors, it is necessary to promote educational opportunities among girls, encourage their enrollment in programs in these fields, possibly through quotas, and implement support programs during their education and first job search. Promoting corporate policies that allow women to receive training in technical specialities and internships within companies can be a win-win situation for both businesses and the state. Due to the ongoing war and the outflow of male workers, there is already a demand for retraining women to fill vacancies in technical fields.

Implementing programs for consulting and financial support for women entrepreneurs

The experience of the "Own Business" program has demonstrated the demand among women for such support and their interest in entrepreneurship. It is crucial to continue and expand similar programs, ensuring accessibility for women of various socioeconomic backgrounds. Efforts should include initiatives that foster support networks and knowledge exchange among women entrepreneurs. Additionally, providing separate grant support for single mothers would be beneficial.

Conducting informational campaigns aimed at changing gender stereotypes

Such campaigns should have support at the highest levels of the country and demonstrate alternative models of role distribution within families, where partners equally share caregiving and household tasks while supporting each other's professional development. The campaign should also promote women entering "non-traditional" professions and highlight their advantages.

Conclusions

Due to prolonged demographic changes and the war, Ukraine faces critically low birth rates alongside a labor shortage. Addressing this challenge requires balancing these dimensions while considering gender equality perspectives. It is essential to work on changing gender stereotypes, encouraging and supporting women in traditionally male-dominated professions, and rethinking policies to help working parents.

This publication was made possible thanks to the support of the European Union within the project 'Network of Gender Think Tanks: Capacity Development for Advanced Policy Design, Impact Assessment, Strategic Advocacy, and Specialized Policy Communications,' implemented by the Ukrainian Women's Fund. The content of this publication is the responsibility of the NGO Vox Ukraine. The information presented does not necessarily reflect the views of the EU and UWF.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations