President Zelensky’s intention to reduce the number of members of parliament from 450 to 300 may appeal to many Ukrainians who have little esteem for Verkhovna Rada in high esteem. But could it really make Ukrainian politics better? Here is what political science has to say.

- One step away from a vote in Rada

- The “ideal number” of MPs: technical arguments

- Why does the number of MPs change in other countries?

- Any connection between quantity and quality?

- Comments from political scientists

- Sarah Whitmore (Oxford Brookes University )

- Yuriy Matsievskyi (National University “Ostroh Academy”)

- Brief summary

One step away from a vote in Rada

The initiative to reduce the number of MPs from 450 to 300 is back on the agenda. On January 14, the respective bill, which also incorporates a proportional electoral system in the Constitution, was supported by the Verkhovna Rada Committee on Legal Policy. 300 votes are required to pass the Law (in February 2020, Parliament initially approved the bill by 236 votes).

The move’s supporters claim it would help cut the costs on Rada’s maintenance and improve the quality of MPs by increasing competition for the seats. They justify the proposed number of MPs by citing a formula that determines the legislature’s optimal size based on a country’s population.

Many Ukrainians do not think much of their representatives in Rada and support any initiatives that aim to “punish” the MPs or reduce their role. According to the organizers of Volodymyr Zelensky’s recent “questionnaire”, about 90% of respondents approved of the idea to downsize Rada.

However, how justified is this initiative and what can its implications be?

The “ideal” number of MPs: technical arguments

Olha Sovhyria, deputy head of the parliamentary Committee on Legal Policy, emphasizes that the number of 300 MPs is derived from the Taagepera formula. It puts the optimal size of Parliament as equal to the cube root of a country’s population:

According to Taagepera, the formula makes it possible to resolve the following contradiction: on the one hand, the more representatives there are, the better they mirror the citizens’ needs. On the other hand, the more MPs, the harder it is for them to reach an agreement among themselves and the more time consuming the legislative process is.

The number of elected representatives should reportedly tend toward the value described by the formula because deputies will then best divide time between their contacts with voters (higher time costs in the case of a smaller parliament) and their interaction with each other (lower time costs in the case of a smaller parliament).

However, contrary to what Sovhyria said, this formula is by no means a generally accepted standard or an ideal to strive for. First, it is based on an abstract model that overlooks a number of important factors. Omitting various political motives at play, the number of MPs may be influenced not only by the number of the population, but also by its diversity (the presence of ethnic and other minorities), degree of decentralization, the number of administrative units etc. Second, the logic behind the formula seems to primarily work for the majoritarian component of the electoral system (contacts with constituency voters). There is also no evidence that the quality of parliament is indeed higher if its size is closer to what the formula predicts.

Cross-country studies show that the size of parliaments does generally correlate with the Taagepera formula, yet it also correlates with other similar theoretical formulas. Furthermore, the formula is not good in actually predicting changes in the size of legislatures over time.

Another issue is that, to justify a reduction in the number of MPs to 300, according to this formula, the population of Ukraine would have to be 27 million. But if we take the 37.3 million cited by the “servants of the people” as a base, the number of seats should be 334. Moreover, according to the State Statistics Service, there are 41.7 million people living in Ukraine (the data for Crimea not included), i.e. the number of MPs should be 347 or even higher if we take Crimea into account.

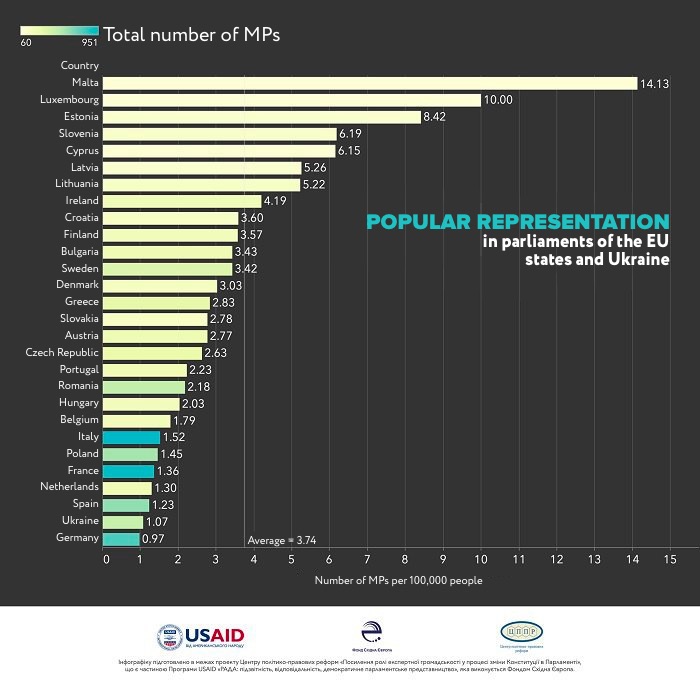

If we simply look at the number of seats per 100,000 of the population, it is already one of the lowest in Europe, though it does not differ much from the countries with a similar population. On the other hand, both 1.07 and 0.72 seats (after reduction) per 100 thousand Ukrainians are just numbers and do not necessarily indicate much about the quality of representation.

Sources: blog in the “Livy Bereh” by Oleksandr Marusiak, expert at the Center of Policy and Legal Reform; population data according to the State Statistics Service, as of early 2020.

Why does the number of MPs change in other countries?

Changing the size of parliament is by no means easy. It is usually the MPs themselves that need to give their approval to downsizing the parliament. “Do turkeys vote for Christmas?”. Sometimes they do.

An increase or a decrease in a country’s population change is, however, not the main reason behind a change. It does often come up in the discussions and is indeed important when it comes to expanding a legislature. Yet when it comes to reducing the number of MPs other factors are at work.

The initiators of such moves usually point to potential cost cutting and increasing a parliament’s efficiency.

However, a detailed study by Jacobs and Otjes shows that reductions in the number of MPs primarily occur during economic recessions. It appears that by offering such a symbolic sacrifice politicians try to reduce popular discontent with public spending cuts.

For example, it was in 2011, in the midst of fiscal austerity, that the British Parliament supported trimming the number of MPs from 650 to 600. When he introduced the measure, Prime Minister David Cameron referred to the scandal about several MPs misappropriating public funds.

In their interviews with researcher Alex Marland, Canadian ex-politicians confirmed that their initiatives were usually designed as a symbolic move that paved the way for painful budget cuts. They did not mention that saving on MPs’ expenses – which is often cited by the proponents of the idea – had any bearing on the decision.

Of course, downsizing a parliament – especially if it involves reviewing electoral rules – is often opposed by those professional politicians (parties) whose jobs (votes) are on the line. Novice politicians and those who no longer stand a chance of being re-elected usually vote “in favor”.

Some initiatives to reduce the number of MPs come from new political forces that ride the wave of discontent with politicians and promise to “punish” the political elites.

For instance, French President Emmanuel Macron promised to cut the National Assembly by a third after defeating “old” parties in the presidential and parliamentary elections.

In 2011 in Hungary, after years of economic decline and catastrophic high-profile scandals, the government led by populist Viktor Orbán nearly halved the number of MPs, from 386 to 199.

In 2020, at the eighth attempt in decades, the number of deputies in Italy was cut by one third. Both houses of parliament and 70% of the participants in the referendum voted in favor. The initiative had been pushed for years by the left-wing populist Five Star Movement party.

Critics say such decisions are often aimed at weakening the legislature, divert attention from more important issues and exacerbate radicalization.

Any connection between quantity and quality?

There are few studies on the impact of the size of a legislature on its quality.

Most statements about the expected implications are limited to the direction of an impact and do not say much about its strength. There are valid objections to some of these arguments.

- For example, some Ukrainian commentators believe that a reduction in the number of MPs will make it easier to “buy”, intimidate, or otherwise persuade legislators to act in the interests of oligarchs and other political wheeler-dealers.

However, in case of a smaller parliament, the weight of each deputy’s vote increases, just as does its potential “value” or “price” for the groups of influence. Conversely, it is easier to get access to an individual MP and the tools available to them when there are more MPs. A recent study on Brazilian municipal councils found that a higher number of deputies is indeed associated with a higher level of corruption, although the link disappears if additional seats are won by opposition.

- Some call a greater “visibility” of individual parliamentarians to society an advantage of a smaller parliament. This could reportedly make it easier for Ukrainians to select a certain number of professional MPs and control them afterwards. However, it is arguably the mechanisms for selecting future candidates (election rules, rules for compiling party lists, relations within the parties, etc.) and exercising control over MPs’ actions that play a much bigger role here.

If there are fewer seats, the struggle for them intensifies, both between and within parties – for a higher place in the party list and for vote in open list voting in regional constituencies. Those advocating for a smaller parliament believe that this should help select the best candidates and weed out the “weaker” ones.

On the other hand, some MPs will need even more resources to conduct their election campaign to get into parliament, which they will have to somehow “return” later. This will further reduce the chances of those candidates who do not have access to significant resources and may increase the dependence of deputies on financial-industrial groups and narrow interest groups. Moreover, some political scientists point out that it is representatives of various minorities or less influential groups who usually end up out of a smaller parliament.

- Rada’s downsizing can hurt the prospects of smaller political parties. They will have fewer attractive positions for their members. The consequences can be negative since creating and developing political forces that are independent of oligarchic groups and “charismatic” leaders is often seen as paramount to changing the rules of the game in Ukrainian politics.

- Theoretically, a smaller parliament may fare worse in reflecting the diversity of public interests. But, in Ukrainian realities, the question is how important is it for MPs to work with “ordinary” voters compared to working with their “sponsors” and interest groups?

- Some researchers point to the relationship between the number of MPs and the duration and complexity of the legislative process. For instance, many MPs want to get seats in parliamentary committees, through which all bills pass. There are already too many committees in Rada, which slows down the legislative process. But would trimming the number of MPs lead to a reduction in the number of committees and speed up legislative work?

To boot, given a certain level of intrafactional discipline, decision-making still depends more on the decisions of the party leaders than on the number of MPs. Therefore, a reduction in the number of MPs is neither a guarantee of improvement here.

Comments from political scientists

Leonid Kuchma proposed reducing the size of the Verkhovna Rada to 300 members in his constitutional referendum of April 2000, part of measures aimed to make parliament more controllable. That dubious referendum (91% voted in favour of a shrunken legislature) was the president’s attempt to harness populist sentiments as a lever to shift the constitutional balance of power in his favour. It failed because (unsurprisingly) deputies were not willing to vote for it, despite the usual presidential buns and whips, because it ran directly counter to their self-interest. The recent presidential ‘questionnaire’ and legislative initiative to reduce the number of deputies seems torn from the same playbook, and likely to end the same way.

Nevertheless, suppose it were to happen: would it make a difference? In principle, there is nothing wrong with the initiative. With 300 deputies, Ukraine would still be well within European norms for representation in terms of population size (remember that the number 450 was a Soviet legacy, and Soviet norms of representation were based on constituting a symbolic microcosm of society that tended to oversized legislatures with rubber stamp functions). Given the considerable privileges that go with a deputies’ mandate, there is an argument that costs could be reduced or redeployed (say, better terms and conditions for permanent parliamentary staff to help retain the best experts to work on legislation and oversight).

However, the question of implementation (as always) would be crucial. How would electoral law be affected? Would parliamentary committees be restructured (given past attempts to reduce their number along European lines foundered)? (read about the harm from having a considerable number of committees in the piece by CPLR – VoxUkraine)

And there is scope for machinations which could make the parliament even more dependent on forces external to it (primarily the president and financial-industrial groups). Furthermore, if the change was an isolated one, not coupled to other, arguably more fundamental, reforms of the legislature, it would be unlikely to produce any improvement in parliament’s functioning. In short, this seems like a populist move intended to bolster the president’s flagging ratings.

Rada’s downsizing is a populist initiative of the President’s Office, which, however, will not be able to prevent Volodymyr Zelenskyi’s ratings from falling. If such a decision is supported in parliament, it will lead to changes to the Constitution, as well as changes to the Law on Elections of People’s Deputies in terms of the number and size of constituencies. If the next parliamentary elections are conducted under the new rules, the “price” of an MP mandate will increase, but this does not guarantee an increase in quality of the Parliament as populism and technology prevail over the parties’ program policy.

Strengthening parliament’s efficiency is only possible through systematic action in at least three directions. In addition to institutional changes, or changes in the rules, we need to create real program parties. Most of the Ukrainian parties today are “party substitutes” (quasi parties – VoxUkraine) that only outwardly resemble real parties. The process of party building must go from the bottom, and this has to do with the third direction – civic and political education of voters. Only if we succeed in all three areas, can we expect a professionalization of the parliament and its transformation from a lobbying club into a real legislature.

Brief summary

Political science does not offer the ideal number of legislators. Parliaments are usually downsized in the times of economic recession to pave the way for public spending cuts or/and result from populist moves against political elites. Volodymyr Zelenskyi’s initiative arguably aims at boosting his ratings and is not motivated by the desire to find the optimal number of MPs or improve the quality of parliament’s work.

It also appears that a reduction in the number of MPs per se would not have any significant positive or negative impact on how Ukrainian politics works.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations