People’s deputies, in collaboration with the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine (AMCU), propose (Bill No. 5648) that during martial law and for five years after its conclusion or until Ukraine becomes a member of the European Union, monitoring and control over the provision of state aid to economic entities should not be carried out. Furthermore, state aid will be non-public. This poses significant risks of negative impacts on business, corruption, and inefficient use of state and local budget funds. What else does the law propose, and why, despite some beneficial innovations, is it not worth voting for?

What is state aid?

According to the current Law of Ukraine “On State Aid to Economic Entities” (hereinafter referred to as the Law), state aid is the support provided to economic entities from state or local resources that distorts or threatens to distort economic competition by creating advantages for the production of certain goods or the conduct of specific activities. Therefore, the Antimonopoly Committee is responsible for approving (or not approving) the provision of state aid after analyzing its potential impact on competition. The AMCU can also order the repayment (with interest) of illegally granted state aid within two years from the moment of its provision.

The Law defines the process of monitoring state aid and controlling its receipt. State aid can be provided in accordance with other regulatory acts. For example, tax privileges or exemptions will be stipulated in the tax legislation, and subsidies, grants, compensations, and budget programs will be governed by budgetary regulations. Additionally, state or local authorities and state or municipal enterprises can grant specific preferences for economic entities.

Why is it necessary to support competition, and what does state aid have to do with it?

Any business wants to earn higher profits. And to achieve that, they need to gain an advantage over their competitors, such as developing better technology, attracting more customers or more qualified employees, purchasing raw materials at a lower cost, and so on. The efforts of individual companies to become more efficient contribute to the economy’s overall efficiency because other businesses strive to catch up and improve their technologies or make more efficient use of resources. On the other hand, if a monopoly arises in a particular market, consumers in that market are forced to pay higher prices for lower-quality goods, and overall, it results in less efficient use of resources for society. Of course, many nuances are involved – for example, determining whether a specific business is a monopoly is quite complex. And in some markets, natural monopolies exist, which require government regulation (you can read more about competition and monopolies here: 1, 2, 3, 4).

Some businesses gain a competitive advantage through state support, such as obtaining tax incentives or subsidies. The necessity of government assistance and its forms are subjects of heated debates among economists. For example, proponents of the Infant Industry theory argue that the government can support an industry that is just starting to develop (including through import restrictions) so that it can later create jobs and profits for the economy (the electronics industry in South Korea is often cited as an example). However, many questions arise in this regard: who and how will determine that industry A, rather than industry B, will be successful in 10-15 years? Why is it necessary to assist a specific industry instead of creating favorable conditions for overall business development? As a counterexample, one can recall the history of the automotive industry in Ukraine, which had favorable opportunities for development, including high import tariffs and direct subsidies, but without noticeable results. A local example is the attempt by the Irpin city council to create a municipal internet service provider when there were already several private providers in the market, which led to unnecessary expenses from the city budget as this provider failed to become profitable.

Services that constitute a general economic interest do not fall under the definition of state aid. In short, these services are desirable from a societal standpoint but not profitable from a market perspective. For example, postal delivery to remote villages or public transportation services often operates at a loss. Since the list of these services is determined by the Cabinet of Ministers and is relatively short, the registry of state aid may include, for instance, the payment by the Pension Fund for Ukrposhta services, funding by local authorities for transportation companies, cultural or sports programs—essentially, anything that corresponds to the definition of such socially essential services. Therefore, a positive aspect of the proposed legislation is permitting authorities to independently determine socially important services and procure them through auctions or a “cost+” method. Of course, granting more decision-making authority to governmental bodies will require them to possess the corresponding competence and integrity. However, in our opinion, competition is the best incentive to avoid the temptation of dishonest decision-making, so any procurement process should incorporate an element of supplier competitiveness.

How much do the state and local authorities spend on state aid?

In short, it is unknown. The Register of State Aid to Economic Entities currently contains 268 instances of its provision since 1997, totaling 117.8 billion UAH. However, the criteria for including specific payments in the register are unclear. For example, the record provides funding for several (but not all) theaters, municipal waste disposal sites, or public transport companies. Such funding could potentially be classified as socially significant services or, more broadly, as part of cultural development or urban improvement programs, which do not require approval from the AMCU. Therefore, it can be assumed that many government authorities simply do not report on state aid if they wish to expedite the funding for a particular program.

Furthermore, the amounts of aid are only indicated for 70% of the projects listed in the register—for instance, the benefits for Diia. City or the program for closing unprofitable coal mines, although not free for the budget, are not specified in the register. More questions arise when considering the specific purposes of state aid, which include subsidies for technology parks (but not all of them), certain employment service programs (compensation of social security contributions for employers hiring specific categories of individuals), financing of cultural and sports events from local budgets, and so on. In reality, the definition of “state aid” is extremely vague.

The latest entries in the register regarding the provision of new aid are dated January 2022 (since monitoring of state aid was suspended during martial law and for one year after its termination). According to the register, in 2022, the value of completed projects involving state aid reached UAH 27.5 billion (for comparison, the budget for 2022 allocated UAH 128.5 billion for the economy, industry, agriculture, and infrastructure, UAH 71.4 billion for education, UAH 21 billion for culture, arts, sports, and information policy, and 9.4 billion UAH for environmental protection). The remaining state aid, totaling approximately UAH 90 billion, was partially provided in previous periods and will continue to be delivered until 2047. Therefore, we are talking about significant amounts and long-term projects (with durations of up to 20 years). However, the fundamental question of how much budgetary funds are spent on state aid remains unanswered. Consequently, it is impossible to assess the effectiveness of state aid and whether it has achieved its objectives.

Proposal: over five years without control over state aid

The most significant negative proposal is “hidden” in the Final Provisions of the draft law. While currently monitoring and control over state aid are not carried out during martial law and for one year after its termination, in Draft Law No. 5648, the deputies propose to extend this period by 5 (!) years after the end of martial law or until Ukraine accedes to the EU if it happens earlier. This means that during these five years, the AMCU will not be able to provide its conclusions that the state aid does not distort competition, nor conduct post-audits of state aid and draw conclusions regarding its legality. Furthermore, during these five years, no information on state aid will be published (under the “normal” mode, information about it is published in the register and on the AMCU website).

One of the conclusions of our previous research on state aid is that it is predominantly characterized by manual management and ill-conceived and politically motivated approaches detached from economic expediency. It can be a source of corruption and distort competition. For example, in 2018, the Poltava City Council set significantly lower rental rates for municipal pharmacies compared to private ones, and the AMCU obliged it to cancel this decision. Such distortion of competition can negatively impact not only Ukrainian enterprises but also Ukraine’s international standing (e.g. if foreign companies or governments attempt to argue that the provision of state aid contradicts Ukraine’s commitments in international trade).

The rest of the innovations in the mentioned draft law – harmonization with EU norms, limitation of state aid only to that affecting trade with the EU, and increasing the powers of the AMCU to review state aid – appear to be positive, but in practice, they may create even more uncertainty and opportunities for corruption. Further details are provided below.

Proposal: Harmonization of norms with EU law and increasing discretion of the AMCU

According to the draft law’s authors, it brings national legislation closer to implementing the EU acquis and the Association Agreement. This includes the discussed provision allowing authorities to independently determine socially essential services.

The draft law proposes introducing new, more modern definitions of “economic entity,” “economic activity,” and “advantages.” It also suggests specifying the dates of providing and receiving state aid, not currently defined in the existing law. One “European integration-related” aspect is the provision on establishing a limitation period for the recovery of state aid, which is not present in the current law.

In addition, the draft law proposes differentiating “insignificant” state aid, which does not require notification to the AMCU. Currently, this refers to support totaling no more than EUR 200,000 over three years. The draft law suggests considering aid as insignificant if it falls under the following thresholds: (1) up to EUR 100,000 for freight transport services, excluding the purchase of cargo vehicles (in line with Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1407/2013), (2) EUR 500,000 for providers of services of general economic interest (SGEI), and (3) EUR 200,000 for other cases. These amounts may seem insignificant within the EU context. Still, considering lower salaries and service costs in Ukraine, they could be sufficient to provide a particular enterprise with a significant advantage over competitors. Furthermore, the draft law retains the possibility of increasing the amount of state aid by up to 20% annually without notifying the AMCU.

At the same time, while the current law (Article 6) at least defines (although quite broadly) categories of aid for which notification to the AMCU may not be required, the draft law simply proposes enshrining in legislation that “the Authorized Body may establish exemptions from the obligation to notify state aid, particularly for specific purposes of state aid.” In other words, the AMCU can essentially determine at its own discretion which state aid requires notification and which does not, as “specific purposes” can encompass anything.

The draft law provides more detailed procedures for examining notifications on state aid by the AMCU, as well as the rights and obligations of the parties involved in this process and in challenging the provision of state aid. It introduces innovations that will help the AMCU make more informed decisions. These include extending the deadlines: the examination period for notification of new state aid is proposed to be increased to 20 working days instead of 15 calendar days, the deadline for sending the decision on the initiation of a case to the provider of state aid is extended to ten working days instead of two, and the deadline for sending the decision of the Authorized Body to the providers of state aid is also extended to ten working days instead of three. Furthermore, in case the necessary information for the AMCU to make a decision is not provided, economic entities will be subject to a penalty of 1% of their revenue from the sale of products for the last reporting year (this provision is borrowed from the secondary legislation of the European Commission 2015/1589). On the other hand, these innovations may further reduce the willingness of authorities to notify the AMCU about state aid. Since the boundaries of state aid are pretty blurred, it will be difficult to “capture” state aid that has not been notified.

Proposal: Reducing the burden on the AMCU

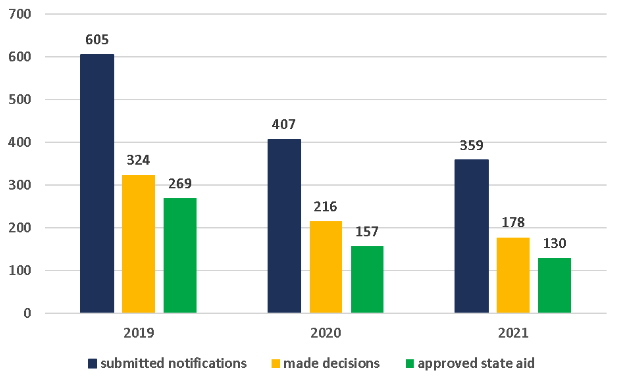

As discussed above, any activity involving state funding can be considered state aid today. The AMCU receives a large number of notifications regarding state aid, which burdens the Committee. Although the number of notifications and corresponding decisions has decreased in recent years (Figure 1), the authors of Draft Law No. 5648 consider the burden on AMCU as the main reason for adopting the law.

Figure 1. Notifications and Decisions of the AMCU on State Aid

Source: AMCU report

For prioritization purposes, the draft law proposes limiting AMCU’s mandate to state aid “to the extent that it may affect trade between Ukraine and EU member states.” While theoretically, this may prevent lawsuits from European companies claiming that Ukraine violates international treaty provisions, it remains unclear how the AMCU and state aid providers (government authorities, local self-government bodies, and others) will determine whether state aid affects trade with EU countries and to what extent. Such vague wording leaves ample room for different interpretations. Furthermore, as discussed in the previous section, competition support is necessary not for the EU’s sake but to ensure that Ukrainians receive higher-quality goods/services at reasonable prices and to allocate resources more efficiently in our economy. In the case mentioned earlier, with lower lease rates for municipal pharmacies, this situation is unlikely to have an impact on trade with the EU. Still, it placed private pharmacies at a disadvantage, which might have resulted in job cuts and/or price increases.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Ukraine will require (and already requires) substantial funds for reconstruction, and considering the experience of corruption (even during the full-scale war, including in the Ministry of Defense), potential donors for Ukrainian reconstruction raise legitimate concerns about the control of funds. However, such control is primarily necessary for Ukrainians themselves because it is more beneficial for us to receive, for example, two schools rather than a school and a house for an official. Some mechanisms for controlling the use of public funds are already in place, such as ProZorro, reports from the Treasury, as well as audits conducted by the Accounting Chamber and the State Audit Service (although these instruments were restricted, at least in terms of public access, during the state of war). It is likely that during the reconstruction process, these mechanisms will need to be strengthened and possibly supplemented with new ones, as reconstruction will affect not only state or municipal infrastructure (such as schools or hospitals) but also private enterprises whose assets were destroyed or damaged by the Russians.

State aid is the most challenging tool both in terms of implementation and control. Therefore, considering the weakness of Ukrainian institutions, it is unlikely that we can simply adopt EU norms. In our opinion, the changes in this area should involve the following:

- maximum simplification: for example, limiting state aid only to direct subsidies and prohibiting tax benefits, debt write-offs, state or local government involvement in the capital of enterprises, and so on. This is because the volume of subsidies can be seen at least in the corresponding budget;

- maximum transparency: disclosing how much state or local authorities spend on financing specific enterprises, as well as the purpose of such funding. In our view, if officials are required to provide well-founded explanations rather than vague statements like “to promote and improve,” the number of cases of state aid provision will significantly decrease;

- risk-oriented approach to monitoring state aid: This means primarily reviewing the assistance received by commercial enterprises, especially state-owned and municipal enterprises whose managers are close to the authorities (e.g., being members of local councils) and belong to sectors that previously had significant oligarchic influence, such as metallurgy and energy. To achieve this, the AMCU should regularly analyze which types of economic entities and activities carry the highest risk of illegal aid and develop selective monitoring to minimize the avoidance of reporting state aid by representatives of the authorities. This could include selective analysis of budgets at all levels and specific decisions of central and local authorities that exhibit signs of risk concerning state aid. The criteria for risk should be constantly updated. It is also advisable to periodically change the sample of objects to be verified to achieve the widest coverage possible.

Restoring control over state aid, to the extent possible, is due now without waiting for the end of martial law. Increased control over state aid should be accompanied by other reforms in the sphere of state and municipal property, such as privatization and the implementation of effective corporate governance. Moreover, there are many ways to support domestic businesses without distorting competition. These primarily include improving the quality of education, particularly adult education (retraining programs), simplifying regulations and reporting, professionalizing the bureaucratic apparatus, and eliminating opportunities for corruption.

According to the Committee on European Integration, Draft Law No. 5648 brings Ukrainian legislation closer to EU norms. However, considering that our level of corruption is significantly higher and the competence of public servants is lower, the harmonization of legislation in this area should be approached in line with our realities. Specifically, while granting greater discretion to authorities in determining socially essential services is generally positive, especially for decentralization, this process should be highly transparent and subject to public oversight to prevent potential abuses.

At the same time, the proposed draft law’s restrictions on control over state aid based only on its “impact on trade with the EU” and the elimination of any control over state aid during and for a period of 5(!) years after martial law essentially dismantle the already incomplete system of control over state aid established by the current legislation. This opens up significant opportunities for corruption and the misuse of budgetary funds. For example, state-owned and municipal enterprises headed by “favorable” individuals would be able to receive budgetary funds or “non-material” assistance, such as tax benefits without any oversight, while providing political dividends in return (such as ensuring “correct” voting by employees or conducting “landscaping” in places of mass events). Needless to say, such “deals” would be highly destructive to Ukrainian democracy. Therefore, we urge the parliamentarians not to vote for this draft law in its current form.

With the support from

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations