Statements from the Ukrainian government periodically emphasize the necessity of repatriating refugees. Occasionally, our officials even appeal to EU countries to cease support for refugees or redirect corresponding funds to Ukraine. However, how do the Ukrainian government and non-governmental programs work directly with refugees?

Representatives of the Ukrainian government periodically emphasize the need for refugees who left due to the war to return to Ukraine. In doing so, they make corresponding proposals to the authorities of the countries where the refugees are residing. For example, during his annual press conference on March 4, the Prime Minister stated that the support programs for refugees in the EU should be replaced with programs that incentivize people to return to Ukraine (in his opinion, the funds currently allocated to Ukrainian refugees in the EU could instead be directed to Ukraine). He also mentioned that Ukraine should work with partners to ensure the security of those returning. Indeed, security is a key factor deterring people from returning. However, as long as Russia has the capability to shell Ukraine with missiles, ensuring full security is impossible.

The article in Politico, released in January 2024, discussed Ukraine pressing the EU for the return of refugees. Additionally, in an interview with a Swiss newspaper, Serhii Leshchenko stated that countries that have accepted Ukrainian refugees should cease supporting them to encourage their return home. This statement sparked outrage in Ukrainian society but also prompted a discussion on how to incentivize refugees to return.

Are refugees willing to return?

A study by Vox Ukraine revealed that only 12% of returning refugees in Ukraine received information from Ukrainian authorities (such as Embassies) that influenced their decision, while 95% of the total number of refugees did not receive such information. This same study showed that the majority of refugees want to return home.

These findings are supported by data from a survey conducted by the UN Refugee Agency in December 2023. It showed that up to 95% of Ukrainian refugees are considering the possibility of returning.

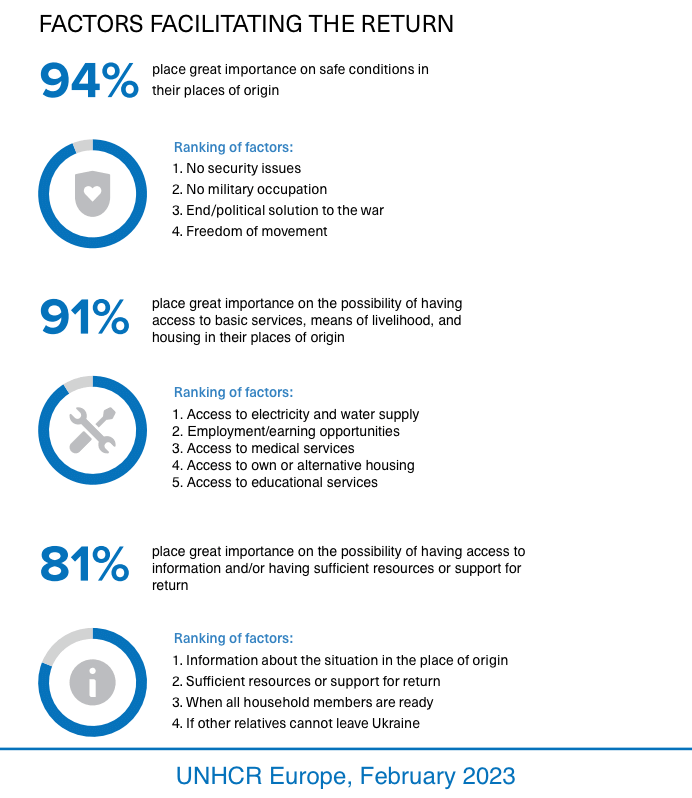

According to the research, while the primary factor influencing the return of refugees is the war, their decision is also influenced by:

- Security in their previous place of residence and access to information about it.

- Access to housing and essential services such as energy supply, healthcare, and education.

- Opportunities to find decent employment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Factors facilitating the return of refugees, according to the UN survey

Therefore, appropriate information and support from the government may encourage refugees to actualize their desire to return.

What does the experience of other countries show?

Some studies argue that returning from a relatively wealthy country to a poorer one rarely happens. However, valuable lessons can also be drawn from negative experiences.

For example, after the civil war, which lasted from 1992 to 1994 between ethnic Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians following the dissolution of Yugoslavia, less than 10% of Bosnian refugees returned to Bosnia and Herzegovina from Northern European countries, despite these states offering generous payments to encourage voluntary return. However, the majority of Bosnians did return from countries that opted for forced return policies. For instance, after the signing of the Dayton Peace Accords in 1995, nearly 300,000 Bosnians returned from Germany. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Bosnian refugees from Germany and other European countries chose to migrate to third countries such as the United States and Australia, Croatia, and Serbia (the latter two due to the ethnic affiliation of refugees with the titular nations of these countries). For Bosnians, “chain migration” was characteristic, where migrants assist family members, friends, and neighbors in migrating.

Despite substantial international assistance (from 1996 to 2004, Bosnia received seven billion dollars, which is the largest financial aid package in history for reconstruction and development per capita), refugees are reluctant to return to this country, likely because interethnic tension remains high, and state institutions are weak.

Research on Syrian refugees shows that intentions to return are significantly influenced by the migrants’ social status, as well as related characteristics such as education and employment. Specifically, refugees engaged in low-skilled work in Syria mostly continued such work in migration and showed less desire to return. On the other hand, refugees with higher incomes, higher education, and employment in intellectual fields more often felt a decrease in social status in the new country and more frequently considered returning in the short term.

Family circumstances and cultural attachment played a significant role: married individuals and those with close relatives living outside Syria were much less likely to seek return while the war persisted. Respondents who believed migration would lead to a loss of culture were more inclined to seek the return. The fear of military conscription is a significant reason for reluctance to return among men and married individuals with children.

Despite the reluctance to return in the short term, many Syrian migrants dreamed of returning in the future. In their imagination, Syria was envisioned as a more free country with a lower level of violence.

One reason for not returning is uncertainty about their ability to secure a stable income in their homeland. For example, research on Afghanistan showed that returnees find it more challenging to find official employment compared to those who did not leave the country.

The peculiarities of Ukrainian refugees

Some of these findings closely resemble what we see in surveys of Ukrainian refugees. Therefore, policies that have worked for these countries could be applied to Ukraine with certain adjustments. For example, married refugees and those with children are less likely to consider returning. Among those employed (45% of refugees), most have found less qualified jobs. Such individuals often view returning to Ukraine as a way to regain lost status. Therefore, government assistance programs for job search and/or retraining (especially considering the current labor shortages in Ukraine in some specialities) could serve as an incentive for return.

On the other hand, Ukrainian refugees undoubtedly differ from refugees from Asian or Balkan countries. For example, according to a survey by the Ifo Institute for Economic Research, the majority of Ukrainian refugees in Germany (from 56% to 65%) hold a master’s degree. Between 15% and 20% of refugees own businesses or are self-employed. According to a survey by the Center for Economic Strategy, only 25% of Ukrainian refugees are “classic” refugees, i.e., mostly middle-aged women with children. For this group, the most important factor for return is the security situation. 29% of refugees are “quasi-labor” migrants who left Ukraine not only because of combat operations but also for work opportunities. For this category, the most important factor for return would not be security but career prospects. Another 29% of refugees are professionals who are not willing to work outside their profession and often have their own businesses in Ukraine. Respondents from this group most often express a desire to return home. For 16% of refugees who left the combat zone, the main factor for return is the creation of necessary conditions for return, as their homes have suffered the most from combat operations.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) regularly conducts surveys of Ukrainian refugees. At the end of 2023, the IOM conducted Round 15 of the General Population Survey, including returnees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). According to it, approximately 1.1 million people, or 26% of those who left after February 24, 2022, returned from abroad. Of these, 87% returned from European Union countries. Among all displaced persons who returned to their permanent places of residence (including IDPs), the most crucial factor was the improved security situation (69% of respondents). 68% of those surveyed indicated that the desire to be closer to family and friends was an essential factor. For 51%, the reason for return was better financial opportunities, and for 28%, better educational opportunities for children. These pull factors were more important than push factors in the places where refugees stayed (such as lack of housing or insufficient financial means).

Programs for Ukrainians provided by host governments

The governments of several European countries are planning to introduce one-time payments for Ukrainian refugees who wish to return. Switzerland may offer between CHF 1,000 and CHF 4,000 per person (approximately USD 1,000 to USD 4,400). Ireland is also considering financial incentives for Ukrainian refugees. Norway already offers NOK 17,500 (~ EUR 1,500) for returnees.

In August 2023, the Czech Republic announced the development of such a program (which will include assistance with document processing and reimbursement of travel expenses). However, at the moment, a similar program (tickets provision) is available only for those, who have been notified of deportation.

The REAG/GARP 2.0 program is available to all refugees in Germany; for Ukrainian citizens, it will become available when hostilities cease. Under the program, the German government and governments of other countries provide one-time assistance of up to EUR 1,000, plus up to EUR 200 for a ticket to the destination country (which can be either the refugee’s country of origin or a third country).

How does Ukraine help those who return?

In October 2023, the Minister of Economy of Ukraine, Yuliia Svyrydenko, announced that the government plans to develop a program to facilitate the return of refugees from abroad. She emphasized four factors influencing the decision to return: security, employment and entrepreneurship opportunities, housing, and education quality. Two of these issues can be addressed through the “eWork” grant program, which helps Ukrainians start or expand their own businesses, vouchers for professional education or skills upgrading available through the State Employment Service, and the “eHousing” subsidized mortgage program, which enables individuals to take out a subsidized loan for housing.

Additionally, refugees abroad for more than 90 days and returning home can receive assistance (UAH 2,000 per adult and UAH 3,000 per child for up to six months after returning to Ukraine). After receiving payments for two months, resettlers are required to find employment or register with the State Employment Center to continue receiving payments. It is unlikely that such assistance alone could be a decisive factor for return (however, it is clear that the capabilities of the Ukrainian budget are very limited).

A factor overlooked by Ukrainian officials is the quality of healthcare. Despite Germany, for example, funding medical expenses, many refugees note better healthcare in Ukraine than abroad. However, due to military actions, one in five people in Ukraine faces difficulties accessing essential medications. The government could address this issue, e.g. by requesting humanitarian aid in the form of medicines from countries unwilling to provide military or financial assistance to Ukraine.

According to the IOM survey mentioned above, the main needs of people who returned from abroad were financial support (52% of respondents), power banks and generators (21%), construction materials (19%), medications and medical services, and heaters and heating fuel (13%). Additionally, 28% of returning respondents indicated the need for psychological counselling. Therefore, refugee reintegration programs could help address these issues. Even in the absence of funds, the government could at least provide the necessary information as many non-governmental organizations assist people in addressing these very issues in Ukraine.

However, the problems of nearly 3.7 million internally displaced persons (according to IOM data as of the end of 2023) also remain unresolved. Among IDPs, 72% need financial support, 41% require heaters and generators, 32% need medications and medical services, 30% require clothing and other non-food items, and 29% need hygiene products. Due to insufficient support for IDPs by the Ukrainian government, some of them may choose to leave the country. Therefore, in addition to refugee return programs, the government and international partners must provide adequate support to those who have remained in Ukraine.

How does the Ukrainian government communicate with refugees?

The Embassy of Ukraine in Germany has a separate section on its website dedicated to temporary protection for refugees in Germany. This section includes information on arrival in Germany, registration, medical services, education, housing, combining studies in Germany with online education in Ukraine, and more. There is a specific page dedicated to educational resources where the Ukrainian Embassy provides information about various educational opportunities, such as links to Ukrainian schools and platforms offering distance learning. There is also information about initiatives of the Ukrainian community in Germany, such as Ukrainian language and literature lessons for children of different ages. Such initiatives will help children reintegrate into Ukraine in case of return.

The website of the Ukrainian Embassy in Poland has no separate sections with information specifically for Ukrainian refugees. However, in the “Assistance to Citizens” section, Ukrainians can find information on various aspects of staying in Poland, such as temporary protection and refugee status, medical assistance, vaccinations, and addresses of Ukrainian assistance centers in Poland. There is also a section about the education of Ukrainian children residing in Poland, with useful links. However, on the Embassy websites, we did not see any calls to return or requests to participate in Ukrainian affairs (e.g., to participate in actions in support of Ukraine).

The website tripadvisor.mfa.gov.ua, developed with the support of the British Embassy in Ukraine and the UNDP, provides information about entry requirements for Ukrainians to countries around the world. For each country with special entry regulations, there is information about entry rules, citizen assistance centers, medical assistance, refugee status, and more.

Conclusions

The return of refugees is not a hopeless endeavor. More than half of those who crossed the border since the full-scale invasion began have already returned. And among those who remain abroad, only 5% have no plans to return. Ukraine is not the first country to face mass emigration, and the international scientific community has accumulated a wealth of knowledge about migrants and the factors influencing their return. This knowledge, along with current research from Ukrainian and international institutions can be applied to develop effective refugee return programs. But above all, there is a need for more intensive communication with Ukrainians living abroad.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations