Sometimes, the central banks get it really wrong, know they got it really wrong, but can’t do much about it (due to domestic politics). Sometimes, they get it really wrong, don’t know they got it really wrong, and, go on bragging about it. The latter is what I think happened in Ukraine in 2011. During 2011, the balance sheet of the NBU shrinks by 17.2 percent. Also during that year, notes and coins in circulation were reduced by 13 percent. By doing so, the NBU starved the nascent economic recovery that was just barely taking hold.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, central banks around the world have become the largest, most powerful, and exceedingly profitable financial institutions. And they can’t wait to get out of this predicament. Central banks are not profit centers. Their main task is to keep inflation on target, while making sure that economic growth is close to its potential.

In this essay I argue that in 2011, the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU), the country’s central bank, made money so scarce that inflation ended up well below the target and the country’s fragile economic recovery turned into a massive recession that continues to this day. I also argue that the NBU should not take an aggressive anti-inflationary stance before economic growth has returned to its potential.

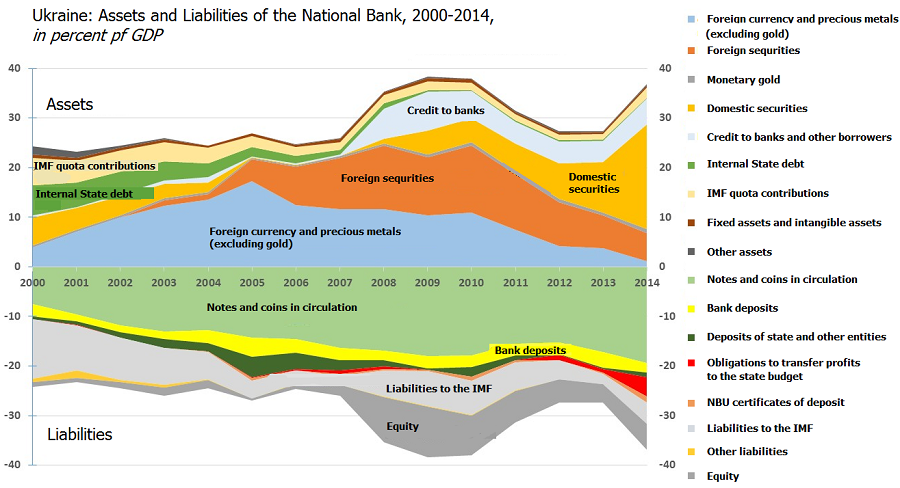

In order to make these arguments, I need to explain the basics of central bank operations. A good place to start is a so-called “balance sheet”. Like any bank, the NBU has a balance sheet. The NBU balance sheet has two sides: assets and liabilities. Assets are what the NBU buys – foreign currency and gold for its reserves, domestic government debt, the debt of commercial and state-owned banks, and so forth. Liabilities are what the NBU uses to pay for the assets – notes and coins in circulation that it can “issue” or “print”, money that commercial and state-owned banks are required to keep on deposits at the central bank, money that government entities hold at the central bank, money that international organizations like the IMF hold there, debt obligations like certificates of deposits and so forth.

Every year, the NBU publishes its annual report in which it discloses its assets and liabilities. The NBU balance sheet for the last 15 years – compiled from its annual reports and scaled by the country’s nominal GDP as calculated by the State Statistics Agency of Ukraine- is summarized in the chart below. For illustrative purposes, assets are presented as positive numbers (a “purchase”) and liabilities as negative numbers (a “payment”).

From the chart, we can see that the assets and liabilities of a central bank expand and contract from year to year reflecting macroeconomic policies and conditions. If a central bank wants to use its balance sheet to do a bit more to stimulate economic activity, e.g., following a crisis, it can do it in three main ways: inject additional money into circulation; allow commercial banks to hold less money in their central bank accounts (this gives more money to the banks to spend elsewhere); and sell less in central bank securities to the financial sector (this also leaves more money in the hands of the financial sector).

During 2008-2009, after the global financial crisis really hit Ukraine’s economy, the NBU did just that: the notes and coins in circulation went up, the money in commercial banks sitting in central bank deposits went down, and the sales of central bank certificates of deposit went down as well. For example, during 2008-2009, the NBU increased notes and coins in circulation from 16.3 percent of GDP at the end of 2007 to 18 percent of GDP at the end 2009 – a 10.4 percent increase. By conducting balance sheet operations, the NBU effectively provided a “monetary stimulus” to the economy. The “monetary stimulus” works if enough of this extra money ends up being invested in real economic projects proposed to the banks by various companies.

Before we look at what has been happening to Ukraine’s companies, now it’s time to mention that for some reason during 2011, the NBU reduced notes and coins in circulation by 13 percent – from 17.9 percent of GDP at the end of 2010 to 15.5 percent of GDP at the end of 2011. A 13 percent reduction in notes and coins circulating in the economy in one year is a really big adjustment. A central bank balance sheet adjustment of this magnitude can be warranted when an economy is really “overheated” or an asset “bubble” is growing somewhere in the financial sector (real estate, particular securities, certain investment projects, etc.) To see if the economy was getting overheated, let’s look at the companies.

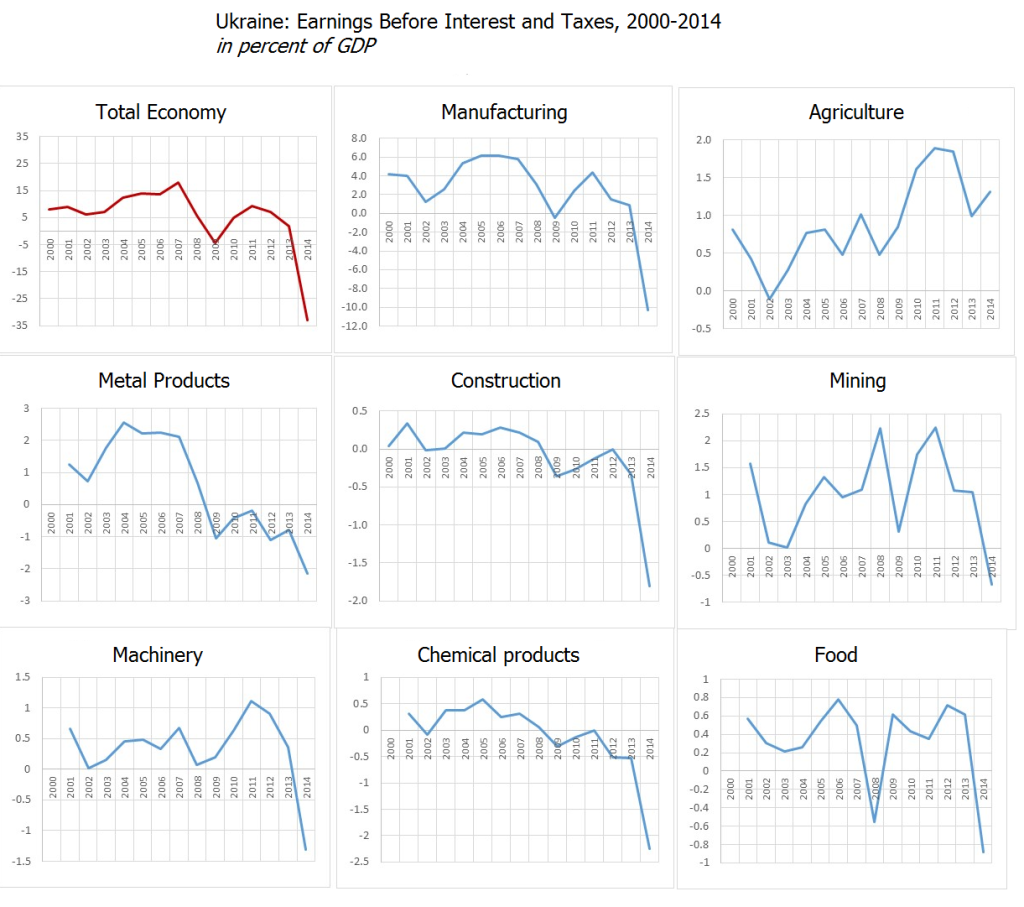

In order to consistently add value, companies need to make at least enough money on their projects to pay interest to the banks and taxes to the government. In the periodic reports that companies have to submit to their governments and shareholders, this economic viability shows up as something called earnings before interest and taxes.

Earnings before interest in taxes for the total economy and by key economic sectors – compiled by the State Statistics Agency of Ukraine and scaled by the country’s nominal GDP – are in the charts below.

In the charts above, it looks like whole sectors of the economy have experienced small, or negative earnings for several years now. This chart, by the way, should be shown to the holders of Ukraine’s external sovereign bonds as Exhibit 1 that the country really does not have the economic capacity to repay them. Such a long period of low or negative earnings–before interest and taxes–does not seem be a temporary phenomenon and is unlikely to turn around anytime soon. Ukraine seems to have gotten stuck between an industrial, resource-based past and a post-industrial, innovation-based future. To help Ukraine get out of this economic limbo, its sovereign debt burden must be reduced.

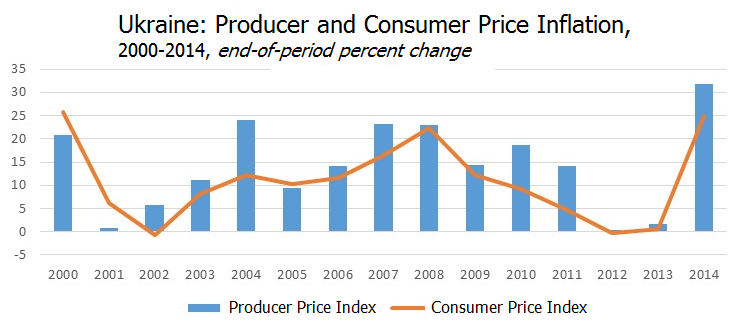

Now back to the companies. One way for the companies to stay viable no matter whether they are resource or innovation-based is to raise prices for whatever it is they are producing and selling to each other and to their ultimate consumers. If these price increases are widespread enough, they show up in the government surveys as producer or consumer price inflation. The dynamics of producer and consumer price indices put together by the State Statistics Agency of Ukraine are presented below.

And now, we are about to come full circle. Central banks, including the NBU, are mandated by the laws of their countries to keep the value of their currency “stable”, so that companies and individuals continue using the national currency instead of switching to another currency. The stability of the currency is typically proxied by domestic price inflation. Low and steady price inflation means that the national currency–in the case of Ukraine, the hryvnya–is stable; high and very volatile inflation means that it is not stable. Another indicator of currency stability is its exchange rate against a major currency, for example, the US dollar. However, if the exchange rate is fixed or heavily managed, as has been the case in Ukraine, the instability of a national currency could build up for a long time without being noticed until it suddenly manifests itself in a devaluation episode, which, in the end, shows up as a spike in domestic inflation.

So, a central bank is mandated to keep inflation low and steady, but, in many cases, including Ukraine’s, the central bank is also supposed to support economic growth. Monetary policy is about squaring this circle: On the one hand, a central bank needs to create more money, channel it to the commercial banks, and “encourage” the banks to lend it to companies. But, companies need to earn enough to pay interest and taxes, so they have to raise prices at least somewhat, which will show up as inflation and make the central bank reduce the amount of money that goes to the banks and so on.

Central banks around the world keep squaring this circle all the time. On top of that, central banks need to keep their financial systems healthy; react to spillovers into the domestic economies from the global economy; and be vigilant about the effects of financial innovations such as new instruments, trading practices, and payment systems.

This is not an easy job, and to in order to do it well, central banks get as much data as they can get their hands on and bring in economic and statistical brains and equipment to comb through this data. The world’s top central banks maintain economics departments that dwarf those of top universities. But, in spite of these brains and data and equipment, central banks still get things wrong all the time.

Sometimes, the central banks get it really wrong, know they got it really wrong, but can’t do much about it (due to domestic politics). Sometimes, they get it really wrong, don’t know they got it really wrong, and, go on bragging about it. The latter is what I think happened in Ukraine in 2011.

So, what seems to have happened in 2011? Let’s look at the balance sheet of the NBU. During 2011, the balance sheet of the NBU shrinks by 17.2 percent. As mentioned above, during that year, notes and coins in circulation were reduced by 13 percent.

By doing so, the NBU starved the nascent economic recovery that was just barely taking hold. A glance at the earnings numbers tells us that – after a small positive bump in the companies’ earnings from 2010 to 2011, earnings went into the negative territory across the board. Negative earnings means that companies have to dip into other means (such as the cash they were going to use to expand their business activity) to pay interest and taxes. If this goes on for several years, as it has in Ukraine, the problems accumulate – banks end up getting saddled with nonperforming company loans and the government ends up collecting less in taxes, plus companies go out of business and have to lay off people.

How did the NBU end up starving the economy in 2011? In order to fight inflation, it made the money that was available to the economy too scarce. The NBU proudly reports in its 2011 annual report that it has successfully forced inflation to historically low levels. Here is a quote:

“We have assured the stability of the national monetary unit. Upon results of 2011, the consumer inflation in Ukraine accounted to only 4.6 percent. This record low figure is of paramount importance for both investors and population of our country. Lower inflation as compared with Government’s forecast for 2011 (8.9 percent) ensured a possibility to considerably save real disposable income, to keep value of population savings, and to lay foundation for further progress in the macroeconomic sphere and in the financial market.

Now, the main task of the National Bank of Ukraine together with the Government is to keep inflation at a low level and to achieve the situation when inflation does not materially influence the investment decisions of economic entities.”

Yes, central bank balance sheet adjustments that result in a 13 percent contraction of notes and coins available to the economy in one year would bring inflation down a lot. But, it would bring economic activity down as well.

Why would the NBU do something like that? One possibility (and that’s a benign interpretation) is that the NBU has misjudged the strength of the economic recovery. It thought that the economy is firmly on the path to recovery and it is time to reign in the prices. That was really wrong. Lots of economic indicators, including stagnant company earnings and asset prices, suggest that it was wrong, but the NBU kept on tightening everyone’s belts all the way to the end of 2013. Only the forced removal of the NBU management in the beginning of 2014 reversed that policy, but it was too late. The economy went into a massive sustained decline and is yet to find the bottom.

What is the lesson for people in charge of the NBU? Please don’t start fighting inflation too early. And when you do, please don’t fight it too aggressively. Yes, I know it sounds bad and, yes, the program with the IMF states that the NBU has to start bringing inflation down to some low levels at some point in the future. Let that time not be 2015 or even 2016 or any time until the economy turns the corner and the companies’ earnings go into the positive territory across the board. I believe producer price inflation of one to one and a half percent per month is a reasonable number to be comfortable with for the foreseeable future. If this means that notes and coins in circulation swell to over 20 percent of the GDP, so be it. The key task right now is to get the economy growing again.

Getting growth out of Ukraine’s battered economy would not be an easy task. There are massive structural problems in Ukraine’s economy – a lot of its growth comes from resource-based projects running on old assets and cheap labor. There are serious problems in the banking system – nonperforming loans, investments in nonviable projects, and value-destroying business plans. There are a lot of problems with financing the government and its pet projects, including incumbent electoral campaigns and state monopolies. To satisfy government financing needs, the NBU has been buying government bonds and “transferring its profits.”

On top of that, there is conflict, destruction, and refugees that need to be taken care of. Solid domestic economic growth is desperately needed in order to deal with all of this. As for the NBU policies that began in 2011 and continued into 2013, they were followed by a loss of human lives, massive suffering and a huge and continuing destruction of values. My hope is that this lesson is learned and the policies of tightening the money supply too early are not repeated too soon.

Disclaimer. These are my personal views. I am not affiliated with the National Bank of Ukraine in any official capacity. I do not hold any financial or business interests related to Ukraine. I did not receive any remuneration for this opinion piece.

Acknowledgements. I sincerely thank Tetyana Tyschuk for work with the data and for preparing the charts.

Notes

- While the focus of this essay is on the balance sheet, there is also, of course, something called off-balance sheet items. We leave them aside for the time being, but the recent acknowledgment of the existence of a swap line with the People’s Bank of China valued at close to 2.4 billion US dollars is a sign that the NBU is not averse to taking on significant off-balance sheet items.

- Nominal GDP numbers are calculated by the State Statistics Agency of Ukraine in accordance with the System of National Accounts 2008, an international standard for the calculation of national accounts statistics. Nominal GDP data for 2000-2013 include data on Crimea and Sevastopol, nominal GDP for 2014 excludes data on Crimea and Sevastopol.

The article initially was published at Huffington Post

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations