How is the labor market situation of Ukrainian workers since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine? In their recent study, Pham, Talavera, and Wu (2023) document a short-term increase in the number of job advertisements ailable for Ukrainian workers to work in Poland after February 2022. In contrast, the number of vacancies in Ukraine remains stable. However, the impacts of war on the number of job ads vary with skill levels and the degree of gender segregation. Further analysis suggests that Ukrainian workers are offered lower wages since the escalation of the war.

Wars can have detrimental socio-economic effects on conflict-ridden countries. Among other, economists are particularly interested in understanding the labor market outcomes for refugees as the impacts could have long-term consequences for the post-war economy. Previous studies have shown that compared to economic migrants and local workers, forced migrants have lower incomes and employment rates (Cortes, 2004; Bauer et al., 2013; Ruiz and Vargas-Silva, 2018; Fasani et al., 2022). These outcomes are often attributed to the mismatch between skills possessed by forced migrants and those demanded in the hosting countries, as well as the lack of language knowledge which is important for the labor market integration. Although some lessons from the literature could be applicable to the ongoing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, direct evidence of the impacts of the war on the Ukrainian workers’ labor market is still needed for both immediate and longer-term strategy planning. In a recent study (Pham et al., 2023), we provide such evidence by analyzing a unique dataset containing millions of online vacancies posted on jooble.org (specifically, we look at vacancies with locations in Poland).

This source of data offers several advantages for examining the labor markets for Ukrainian workers during wartime. First, the data are updated in real time, hence, allow us to continuously document the trends in labor markets for Ukrainians as the war continues. Second, using information on job locations, we are able to differentiate the job ads targeting Ukrainian job seekers who migrated to other countries (migrants) versus those targeting job seekers who stayed in Ukraine (stayers). In our analysis, we focus on comparing jobs in Ukraine and Poland since Poland is one of the main destinations for Ukrainian refugees.

Jobs in Ukraine versus jobs in Poland

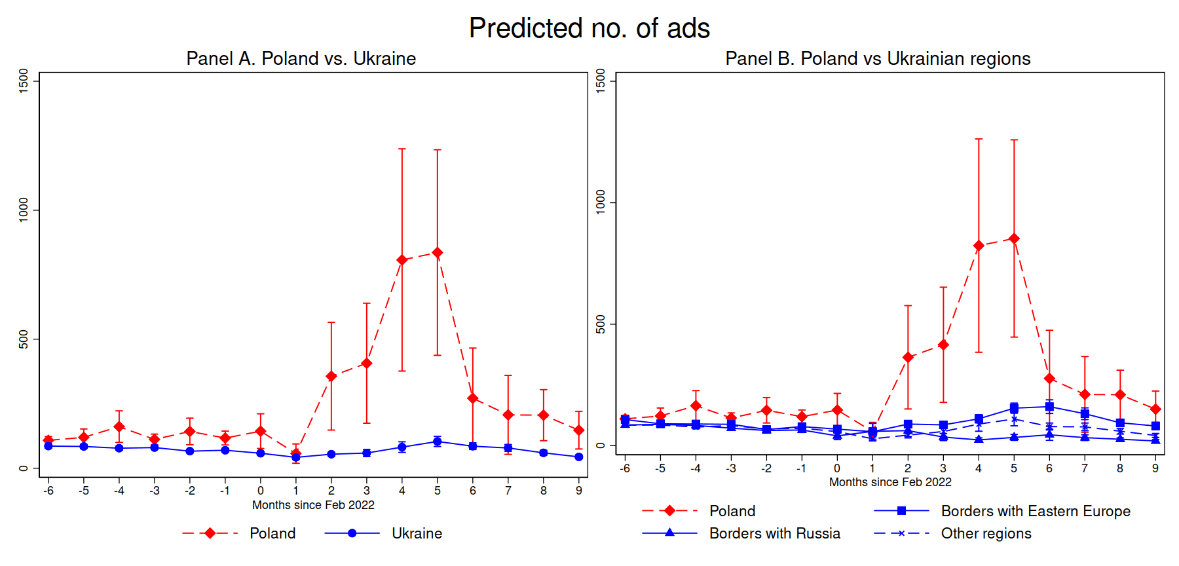

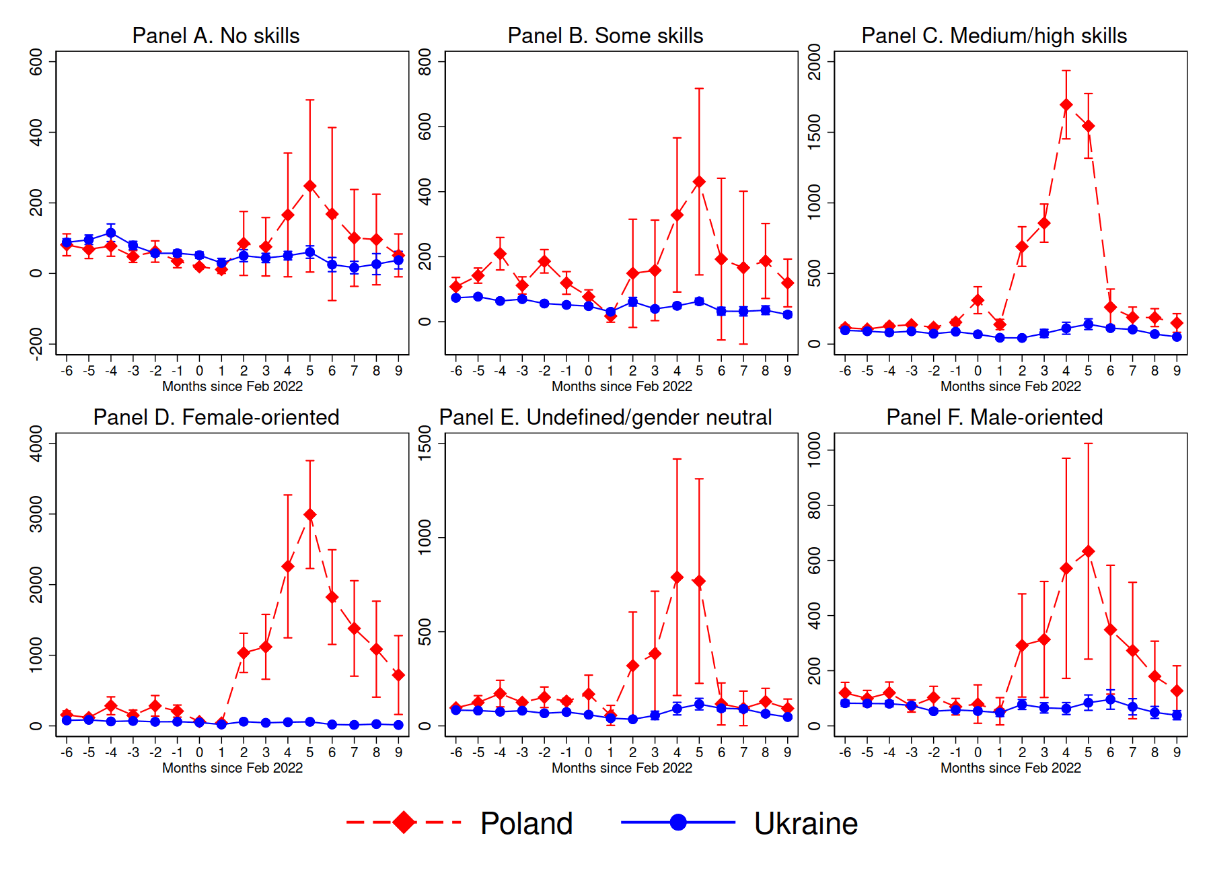

Since the onset of the full-scale invasion, the number of job vacancies for Ukrainian workers to work in Poland has increased sizeably. As shown in Panel A of Figure 1, the average predicted number of these vacancies increased from 100 a month before February 2022 to 800-840 in June-July 2022. Since August 2022, the number of Polish vacancies targeting Ukrainians started to decrease but was still higher than the pre-February 2022 level. Moreover, the impacts of war on demand for Ukrainians to work in Poland are more pronounced for jobs that require medium or high-level skills and that are in women-oriented occupations (Panels A-C, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Predicted number of job ads by job location

Notes: This figure shows the predicted number of vacancies by job location. The adjusted predictions with 95% confidence intervals are reported. Predictions are obtained from regressed share of ads on locations, fighting intensity, and a battery of fixed effects.

Although we do not observe any significant difference in the number of online vacancies in Ukraine before and after February 2022 (Panel A, Figure 1), there are some variations across regions. Particularly, after February 2022, most online vacancies were for jobs in Ukrainian regions sharing borders with Eastern Europe. In contrast, the number of jobs in regions sharing borders with Russia was smallest with a decreasing trend. What could be the reasons behind these trends? First, firms that still operated after the onset of the full-scale war might need to find new workers to replace those who left the country. In other words, the new advertisements are to fill the existing jobs that were left vacant because of the war. Second, many firms had moved businesses to the West of Ukraine, increasing the need to find workers in the new locations.

Figure 2. Predicted number of job ads by location and job heterogeneity

Notes: This figure shows the predicted number of vacancies by skills categories (Panels A-C) and occupational gender segregation* (Panels D-F). The dashed line represents the results for jobs in Poland while the solid line represents the results for jobs in Ukraine. The adjusted predictions with 95% confidence intervals are reported.

* In the spirit of Cortes and Pan (2017), we use O*NET’s Work Context data9 to classify jobs into female vs. male-oriented. A title is considered to be male-oriented if the scale of “Spend Time Climbing Ladders, Scaffolds, or Poles” or “Spend Time Using Your Hands to Handle, Control, or Feel Objects, Tools, or Controls” is at least 80. A title is considered to be female-oriented if the scale of “Contact With Others” is at least 80. Any titles that (1) cannot be matched with O*NET titles or (2) are not mutually exclusive of the female versus male category are considered undefined (or gender neutral in a loose sense). In other words, for each normalized job title, the Gender variable will be equal to 0 if female-oriented, 1 if undefined, and 2 if male-oriented.

Skill requirements and wages offered

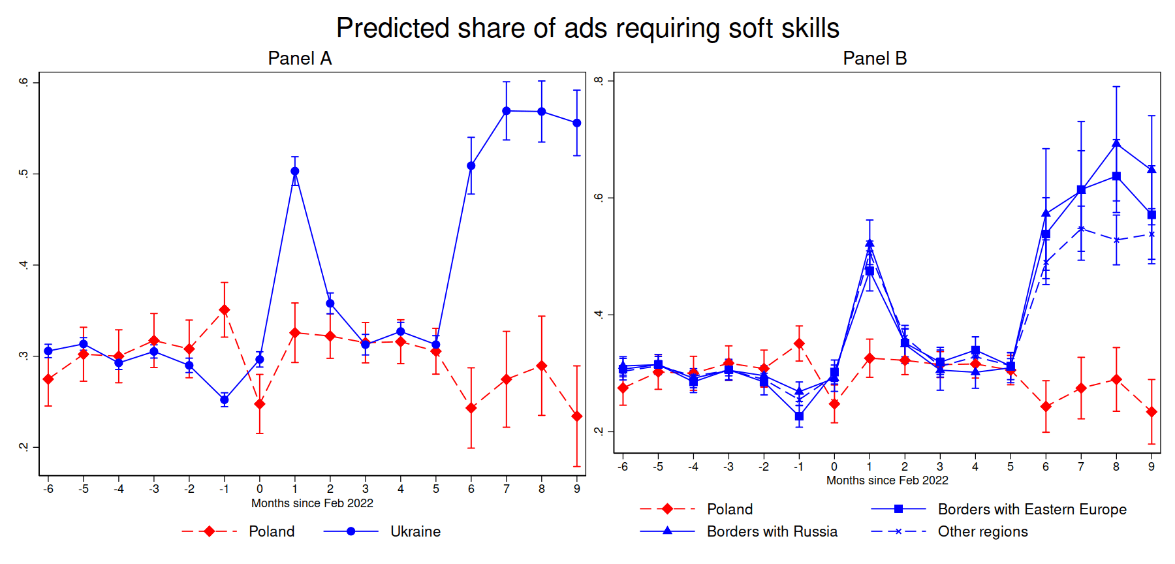

Has the demand for skills changed since the onset of the full-scale war? On the one hand, the share of advertisements in Poland requiring soft and analytical skills does not change significantly over time (Panel A – Figure 3). On the other hand, Ukrainian firms tend to request such skills more often in the advertisements posted after February 2022. Unfortunately, the increasing demand for soft and analytical skills does not transfer to the higher offered wages. In fact, we observe the decrease in real wages offered to Ukrainian workers after February 2022, regardless of work location and job profile. The fall in wages is larger in Ukraine than in Poland and medium/high-skilled occupations are slightly less affected. For example, the real offered wages of vacancies posted in Ukraine since April 2022 is 60% lower than the real wages offered in March 2022 while the drop in real offered wages of Polish jobs is in the range of 9%-18%.

Figure 3. Predicted share of ads requiring soft and analytical skills

Notes: This figure shows the predicted share of vacancies requiring soft skills. The adjusted predictions with 95% confidence intervals are reported.

Conclusion

Lessons from history seem unlikely to provide us with a full picture of what happens now in Ukraine. The substantial increase in the number of job vacancies in Poland available to Ukrainian workers at the beginning of the full-scale invasion could help mitigate the concern about the labor market integration of Ukrainian refugees. Nevertheless, this short-lived trend, coupled with the persistent decrease in offered wages, suggest that more needs to be done, e.g., language courses or formal recognition of Ukrainian workers’ skills (Botelho and Hägele, 2023), to improve the labor market outcomes of Ukrainian refugees. Additionally, given the suggestive evidence of the changes in skills requested by Ukrainian employers, relevant policies such as skills training are necessary so that workers are equipped with highly-demanded skills which are important for their labor market outcomes in the post-war era.

References

Bauer, T. K., Braun, S., and Kvasnicka, M. (2013). The economic integration of forced migrants: Evidence for post‐war Germany. The Economic Journal, 123(571), 998-1024.

Botelho, V. and Hägele, H. (2023) Integrating Ukrainian refugees into the euro area labour market. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2023/html/ecb.blog.230301~3bb24371c8.en.html (Accessed: 26 July 2023).

Cortes, K.E., 2004. Are refugees different from economic immigrants? Some empirical evidence on the heterogeneity of immigrant groups in the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2), 465-480.

Fasani, F., Frattini, T., and Minale, L., 2022. (The Struggle for) Refugee integration into the labour market: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 22(2), 351-393.

Huber, K., Lindenthal, V., and Waldinger, F., 2021. Discrimination, managers, and firm performance: Evidence from “Aryanizations” in Nazi Germany. Journal of Political Economy, 129(9), 2455-2503.

Pham, T., Talavera, O., and Wu, Z. (2023). Labor markets during war time: Evidence from online job advertisements. Journal of Comparative Economics.

Ruiz, I. and Vargas-Silva, C., 2018. Differences in labour market outcomes between natives, refugees and other migrants in the UK. Journal of Economic Geography, 18(4), 855-885.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations