Following the plans of Volodimir Zelenskyy to reach a peace deal in Donbas, a new Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies paper estimates the reintegration costs of Donbas. We estimate that the lower bound on reconstruction cost would be $22 billion. Almost a half of this sum will be needed for reconstruction of physical capital, followed by expenses on human capital and environment.

Peace plans reloaded?

As Neta Crawford – Professor of Political Science at Boston University – has carefully noticed “a full accounting of any war’s burdens cannot be put on columns of a ledger”. Yet it does not mean that the attempts to do so are useless. Even if one might never calculate a proper compensation for a human loss, one can still figure out how much should be done to improve well-being of the living people: be it an elderly in the waiting queue to cross the line of contact or a schoolgirl hiding inside of a bomb shelter in the middle of a lesson.

The landslide victory by Volodymyr Zelensky in the last elections turned a new page in the government attempts to end the war in Donbas. Nonetheless, the factual basis for the reintegration plans remains vague. Lack of credible information on the economies of the occupied region creates uncertainty with respect to the magnitude of the reintegration costs. Although wiiw study is not unique in estimating the costs of war (see here and there), it stands out in three respects. First, the study is the first one to explicitly model the costs of war for both government-controlled territories and the certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions (CADLRs). Second, it documents the evolution of the macroeconomic and humanitarian issues for the CADLRs from the conflict onset until the end of 2019. Third, it evaluates the war in Donbas in light of other war-torn countries and highlights the fundamental problems – apart from those related to foreign intervention – that hinder the peace process.

The Costs at Glance

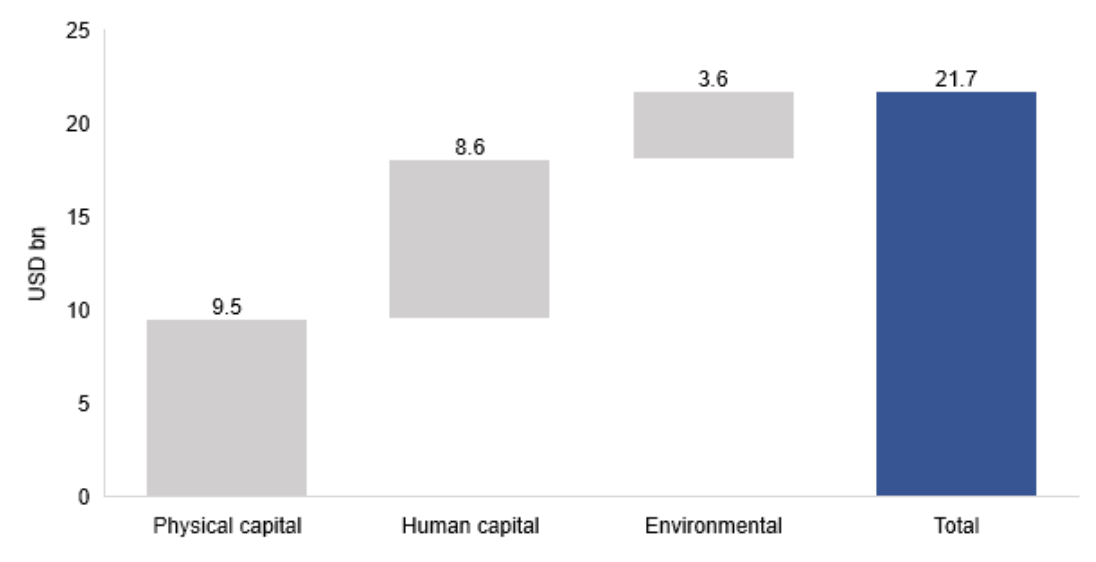

The report estimates the lower bound of reconstruction costs at USD 21.7 bn (figure 1). This is equivalent to one-third of Ukraine’s state revenues in 2019 and is greater than the annual GDP of a small country like Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Figure 1. Estimated lower bound of reconstruction cost decomposed

Source: own calculations. For details see the Methodology box below.

The report underlines several channels through which the costs were propagated: direct damage, capital depreciation, environmental problems, and humanitarian issues.

Direct damage

Part of costs – albeit not the biggest one – arises due to direct damage caused by armed warfare. Both sides use a wide range of heavy arms such as self-propelled howitzers, tanks, and multiple rocket launchers. Since Donbas is a heavily urbanised region, most of civilians and fixed assets are highly exposed to collateral damage caused by this weaponry.

Apart from that, the conflict is characterized by an extensive use of landmines to reduce options for potential advancement of either side. As a result, Donbas is now the third-most landmine-contaminated region in the world behind Afghanistan and Iraq. Landmine clearance is a necessary prerequisite for the reconstruction to assure security of the population.

Capital depreciation and environment

After the break-up of the Soviet Union, the region inherited a large amount of fixed capital assets. This property allowed to reduce average costs of production and assured an upper hand on the production markets of mining and heavy industry. On the other hand, fixed assets require regular maintenance and reinvestment to assure continuity of the production process. The inability to raise revenues and continue business as usual led to investment cuts and depletion of fixed capital, which has been accumulating since 2014.

Because of that, many enterprises stopped maintaining the coal mines, most of which became unprofitable. This has raised risks of geological instability of the terrain and environmental pollution through the contact of surface waters with mine waters contaminated by heavy metals. To avoid an environmental disaster, the coal mines should be properly liquidated adding another item to the cost budget.

Humanitarian issues

The economy of Donbas operates in the midst of a humanitarian crisis. Armed warfare, restrictions on the freedom of movement, and limited access to social services had a massive footprint on the local population. 30 thousand people were injured, 1.4 million became displaced and 3.4 million experience lack of basic goods such as housing, security, psychological support, and food. To recover the region, the restoration programme should address these needs and assist displaced persons in returning back home.

The Plan

The conflict has reached a stage when armed skirmishes themselves are not the largest contributors to the economic setback of the region. 42% of the total costs are composed of uncovered depreciation of fixed assets and liquidation of coal mines. This result suggests that these costs do not arise due to direct damage. They can be directly attributed to the disruption of business continuity processes and degradation of state capacity. In other words, unloading bullets from the magazines will not suffice to reboot the economy of Donbas – the government needs to develop a full-scale program to restore the basic economic institutions: markets and state capacity. The proposed plan outlines four critical targets.

Demine territories and eliminate environmental threats

Lack of security is the primary reason for internal displacement. A credible ceasefire and disarmament ensure there is no warfare, but do not address the side-effects that continue to threaten the everyday security of the population: landmines and environmental issues. Eliminating both threats at the initial stage of restoration is crucial to avoid health damage after the mass reallocation of the displaced people.

Rebuild infrastructure and reallocate the displaced population

To get the economy of the Donbas back up and running, the reconstruction should restore markets and attract population. This stage would need to address three targets. First, rebuild critical infrastructure in urban areas to overcome the humanitarian crisis. Second, lay foundation for long-term investment by formulating a clear legal framework, which would define rules of property rights transition from the CADLRs’ ‘legal systems’ to the Ukrainian one. Third, the economy of Donbas will also not revive without a qualified labour force, which could be brought back by cash assistance programmes contingent on long-term residence in the region. These would help to overcome the initial challenges caused by poor infrastructure, weak labour markets and an insecure environment for the first settlers.

Promote long-term sustainable economic growth and set the stage for investment in the region

Although improvements in the investment climate are linked to the progress in the Ukrainian reform process, the fragile post-war environment might scare investors off investing specifically in the Donbas region. This perception will, in turn, result in low growth, discontent and greater fragility, which will drive away more investors. To avoid the vicious circle, the state should consider providing preferential investment conditions for the Donbas region at an early stage of the post-war reconstruction. The design of the preferential conditions should incorporate mechanisms that reduce the room for opportunistic behaviour and moral hazard. The preferential schemes should be accessible and applicable to both big corporate entities and SMEs to avoid excessive concentration of assets as it was before the war.

Support post-war resilience

The reconstruction efforts do not end once the pre-war GDP levels are reached. Post-war security is fragile, and only a broad legitimation of the government in power can ensure that the local population does not follow a call to rebellion regardless where it comes from: be it internal or induced from the outside. This is why the long-term resilience requires inclusive institutions: mechanisms of collective decision-making that guarantee political participation, minority rights and public goods provision. The state should support administrative capacity and political engagement of the CADLRs in the long term to avoid dissatisfaction and ensure fair representation of local interests at the state level.

Conclusion

It might be tempting to use the results of this report to reinforce the dominant antagonistic narratives across the conflict sides. The message of the report, however, is different. The core part of the report raises awareness about the humanitarian issues and what approximate scale of efforts is required to bring the local economy back on track. Those who oppose the negotiation process should be aware that those humanitarian issues are the opportunity costs of peace, which Donbas citizens carry on their shoulders every day.

The other part, which so far was frequently overlooked by the observers, highlights the fundamental problems of the conflict resolution. It’s important to realize that the peace will not appear overnight once the Russian elites stop backing-up the breakaway “republics”. Despite its unique roots, the war in Donbas still shares the same fundamental issue common for designing the peace arrangements: a commitment problem. The inability to credibly assure that the negotiation sides will stick to the agreements is a key problem in most conflict settings, because as long as any of the side lays down arms, there is no guarantee that the other one will not try to take advantage of it undermining the idea of conflict resolution in the first place. That’s why the binding guarantees put on the state and ex-combatants at the highest possible legal level – complemented by external monitoring – are critical in the peace negotiation process.

There is no guarantee that achieving the program targets will lead to a lasting peace. Experience of the war-torn countries shows that slips and tensions are likely to recurrently arise during the conflict resolution. Yet one can increase the chances of a positive outcome if the government provides credible evidence for the local population of a long-term commitment to pursuing inclusive policies. There are several ways to reinforce this feeling but a prosperous state with a solid economy would be the best proof of concept. For that, Ukraine should target the long-standing problems: overcome vested interests and continue the reform path.

Methodology of the estimations

Fixed capital losses

The report evaluates fixed capital losses indirectly, by combining recent survey evidence on household damage with data on battle intensity. The estimation process consists of four major steps. First, the authors calculated the share of housing value lost due to hostilities for a subset of the government-controlled areas based on randomized stratified surveys by REACH (2019) and evaluation of the housing repairment costs by UNHCR Shelter Cluster (2016). In step two, the report estimates the linear relationship between the district-level battle intensity based on Zhukov et.al (2019) and the share of housing damage (as percent of the original value) for the sample of available districts. Assuming that the share of housing lost is representative for the fixed capital, the report uses the estimated coefficients to predict the share of capital lost for all districts of Donbas – both government and separatist controlled. Finally, the report multiplies the shares of capital lost by the district-level estimates of the pre-war capital stock.

In addition to the direct capital damage caused by fighting, the report assesses the amount of capital depreciation. The report assumes that the volume of capital investment in separatist-controlled areas is negligible and the value of fixed assets depreciates at a full rate, where the rate is calculated from pre-war of capital depreciation reported for Ukraine in the Penn World Tables 9.1.

Human capital

The human capital calculations first evaluate yearly expenditures for each cost type (social support or mental health. The yearly costs are calculated based on different sources. To estimate the social support volumes, the reports uses the volume of annual expenditures of the Ukrainian budget on the support of veterans and IDP: USD 164 million. For the mental health costs, the report multiplies the size of the conflict-affected population (5’200’000) with the share of persons with symptoms of psychological disorders (42%) and average treatment costs (USD 54) reported in Roberts et.al (2017). The annual mental health expenditures are thus equal to USD 118 million. The reported values are then projected over the lifetime of the median Ukrainian citizen based on data from PopulationPyramid.com (2019).

Environment

The study attributed two types of costs to the environmental ones: the costs for the landmine clearance and the coal mine closure. For the landmine clearance, the authors used estimations by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence estimated at EUR 650 mn. The liquidation costs of coal mines are based on estimations attributed to the draft report by the Ministry of Energy of Russia on the state of the energy sector of the CADLRs (Informnapalm.org, 2016). In 2016, the ministry assessed the number of unprofitable mines at 120 units, with a liquidation cost of closure of USD 24.5 million per mine using the simplest available technology. Scaling the costs for each mine yields a total cost of mine closure of USD 2.9 billion.

What was left out

The provided estimates for CADLRs rely largely on projections of the costs inferred for the government-controlled territories. Most likely, this approach underestimates the cost components. In particular, the report does not account separately for capital losses for those enterprises, which were fully or partially scrapped or relocated from Donbas to Russia as noted by some observers (1, 2). Additionally, given the limited access to state services and isolated nature of the economies, the share of population requiring social and medical support – including mental diseases – is likely to be greater in CADLRs. The report also leaves out some war-related externalities, such as the spread of diseases due to disruption of the standard sanitation and vaccination activities, expected risks of the technological disasters, and environmental damage caused by munition fragments in the ground, forest fires, and pollution of local water basins.

It is worth noting that the depth and detail of the underlying sources were not equal across the components investigated. As a consequence, the reliability of the estimations is uneven. The fact that the physical capital costs dominate in the overall cost structure partly reflects the degree of ignorance about the other dimensions. For instance, the assessment of human capital costs does not embed the effects of outbreaks of disease caused by disrupted prevention and treatment of otherwise contained infectious illnesses: measles, tuberculosis and HIV.

References

UNHCR Shelter Cluster Ukraine (2016), ‘Cluster guidelines: Structural repairs and reconstruction’, Technical Report, UNHCR

REACH (2019), ‘Ukraine 2019 – multi sectoral needs assessment within 20km of Contact Line’.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations