Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, most journalists, scholars and, to a certain extent, politicians in the Association Agreement countries (AA), have portrayed geopolitical preferences as a choice between the West (the EU, NATO…) and the East (Russia, the Eurasian Economic Union, CIS, CSTO…). This dichotomous framework has the advantage of easing the analyses at the cost of portraying a black and white scenario with two opposing groups. However, the picture is more complicated than that. Relatively recently, Buzogány developed a new four-fold categorization of geopolitical preferences that goes beyond the traditional dichotomy. This article benefits from these developments and uses it to compare geopolitical preferences of citizens in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.

In the essence, using a categorization that divides geopolitical preferences into four groups should help us better depict the geopolitical orientations landscape in post-Soviet Europe and paint a more realistic picture of the situation. For all countries and waves, these four categories are based on two separate (one for each of the International Organizations) questions asking individuals if they would vote for or against joining the EU/EAEU in hypothetical referendums*. The four groups are:

- Balancers: respondents that are in favor of joining both the EU and the EAEU.

- Westernizers: citizens that support joining the EU but not the EAEU.

- Easternizers: individuals that favor joining the EAEU but not the EU.

- Isolationists: respondents that oppose joining both the EU and the EAEU.

* The questions were virtually the same in the three countries and were formulated as “If there were a a referendum tomorrow, would vote for or against membership of Eurasion Union established by the Russian Federation?”, “If there were a referendum tomorrow, would you vote for or against EU membership?”

Once the new categorization is used, two questions arise:

- how similar or dissimilar are the AA countries regarding the distribution of geopolitical preferences?

- what determines support for these new ambivalent categories?

Data

To test these questions, this piece analyzes survey data from Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. These surveys were fielded between 2015 and 2019. In the case of Georgia, I use three surveys that belong to the “Knowledge of and Attitudes toward the EU in Georgia” collected by the Caucasus Research Resource Centers. The seven surveys used for Moldova are part of the “Barometer of Public Opinion of the Republic of Moldova” series fielded by the Institute for Public Policy. Finally, the nine surveys used for Ukraine belong to the “Omnibus” series that the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology collects. All of the surveys that I use for this analysis are nationally representative and have an average sample of ≈2,100 observations for Georgia and Ukraine and ≈1,100 observations for Moldova. Once the main variable (the four-categories variable) is coded, the final number of observations is: 7,149 (Georgia), 7,544 (Moldova), and 17,506(Ukraine).

Distribution and evolution of geopolitical preferences in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine (2015-2019)

Looking at the distribution of the four groups (five, when we add the don’t know/don’t answer group) of geopolitical preferences over the 2015-2019 period in each of the AA countries, we see some common and divergent trends.

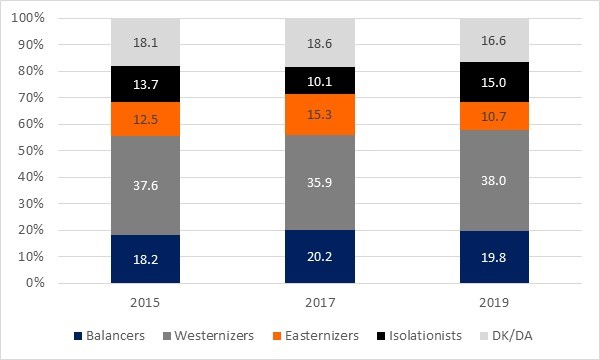

Figure 1. Percentages of support for the different geop. preferences options (average over 2015-2019)

Source: Own elaboration based on Georgia (Knowledge of and attitudes toward the EU in Georgia, 2015-2019), Moldova (Barometer of Public Opinion of the Republic of Moldova, 2015-2019), Ukraine (KIIS Omnibus, 2015-2019).

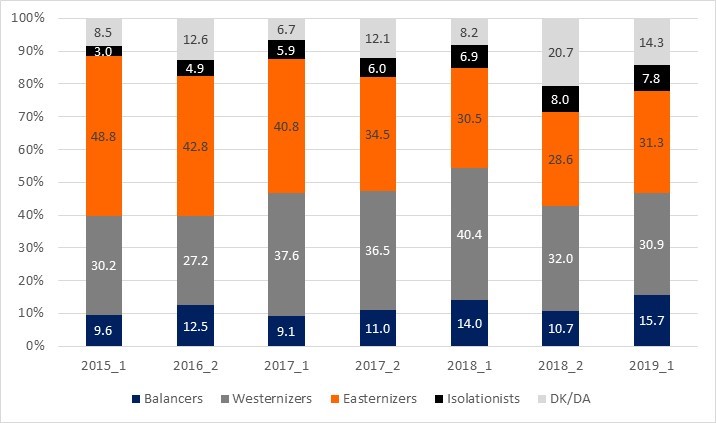

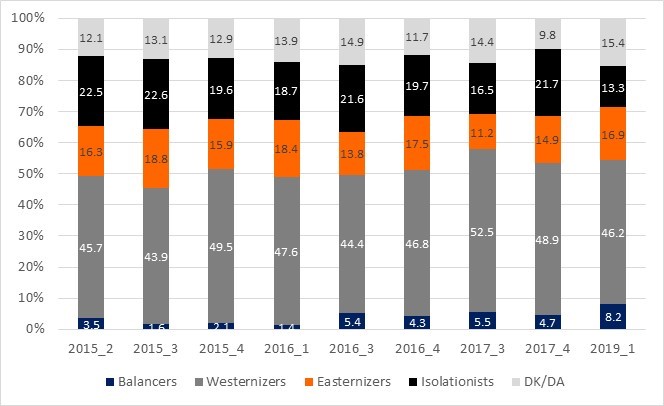

Regarding support for the Westernizer and Easternizer options, the results confirm what is already commonly known: Georgia and Ukraine (figures 2 and 4) show a very dominant position of the Westernizer group during the whole studied period, with Easternizers amounting to around a quarter of the support of Westernizers. Moldova (figure 3), by contrast, shows a very polarized geopolitical preferences landscape in which the percentages of support for the Westernizer and Easternizer options experience notable changes during the 2015-2019 period. In spite of the volatility, however, the percentages of support for these two geopolitical options tend to remain very similar throughout the whole period.

Figure 2: Evolution of geopolitical preferences in Georgia (2015-2019)

Source: Own elaboration based on Knowledge of and attitudes toward the EU in Georgia, 2015-2019.

If we consider ambivalent geopolitical preferences (Isolationists and Balancers), on the one hand, the results indicate that in both Georgia and Moldova, these orientations amount to a very important percentage of the population, with a higher percentage of Balancers than of Isolationists in both countries. In addition, both Georgia and Moldova show a clear increase of the ambivalent positions during the studied period, which correlates (especially in the Moldovan case) with a decrease in the rates of support for the EU and the EAEU. This could indicate a downward trend in the geopolitical preferences polarization in the country. On the other hand, Ukraine shows a different scenario regarding the ambivalent positions: in this country there are many more Isolationists than Balancers. The almost negligible role of Balancers in Ukraine could have to do with the ongoing conflict with Russia, which could have made the population realize that maintaining good relations with both the EAEU and the EU is a very unlikely scenario. Nevertheless, it is important to note that there seems to be an increase of the Balancer option in Ukraine, most probably from respondents that used to support the Isolationist option.

Figure 3: Evolution of geopolitical preferences in Moldova (2015-2019)

The numbers after the years (i.e. 2015_1) represent the number of the survey in the year, in this case, the Barometer of Public Opinion is fielded two times per year. Source: Own elaboration based on Barometer of Public Opinion of the Republic of Moldova, 2015-2019.

Figure 4. Evolution of geopolitical preferences in Ukraine (2015-2019)

The numbers after the years (i.e. 2015_2) represent the number of the survey in the year, in this case, KIIS fields four Omnibus surveys each year. Source: Own elaboration based on KIIS Omnibus, 2015-2019.

Determinants of support for the ambivalent geopolitical preferences in the AA countries: common and divergent trends

In an article published in Post-Soviet Affairs, I analyzed which characteristics may impact geopolitical preferences of a person.

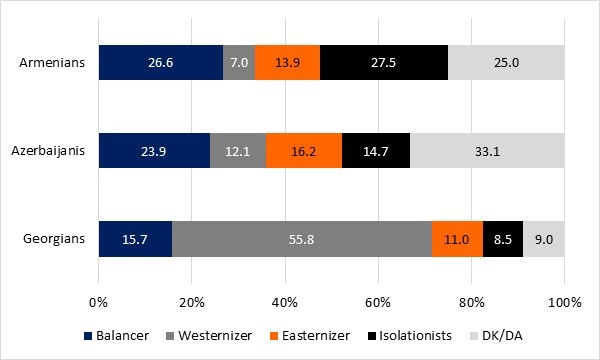

A first relevant set of results has to do with self-reported ethnicity **. Figures 5-6 summarize the distribution of geopolitical preferences amongst the main ethnic groups of each of the AA countries. These figures show the main trend shared by all ethnic minorities in the three countries (except Romanians in Moldova): minorities tend to be less in favor of the Westernizer option and more of the Easternizer path than the titular nationalities of the AA countries. Regarding ambivalent positions, however, we see diverging trends in each of the countries with (1) minorities tending to be more Balancers and Isolationists than Georgians in Georgia, (2) less Balancers and more Isolationists than ethnic Moldovans in Moldova, (3) and less Balancers and more Isolationists than Ukrainians in Ukraine.

** Across this article, following the Georgian and Moldovan surveys’ terminology, I refer to ethnicity/ethnic groups, however, it is important to note that the surveys and scholars in Ukraine tend to refer to this same concept as nationality.

Figure 5: Distribution of geopolitical preferences in each ethnic group, Georgia (2015-2019).

Georgians N=4,264, Azerbaijanis N=1,480, and Armenians N=1,271

Source: Own elaboration based on Knowledge of and attitudes toward the EU in Georgia, 2015-2019.

Figure 6. Distribution of geopolitical preferences in each ethnic group, Moldova (2015-2019).

Moldovans N=5,897, Ukrainians N=502, Russians N=371, Gagauz N=308, Romanians N=253, and Bulgarians N=135

Source: Own elaboration based on Barometer of Public Opinion of the Republic of Moldova, 2015-2019.

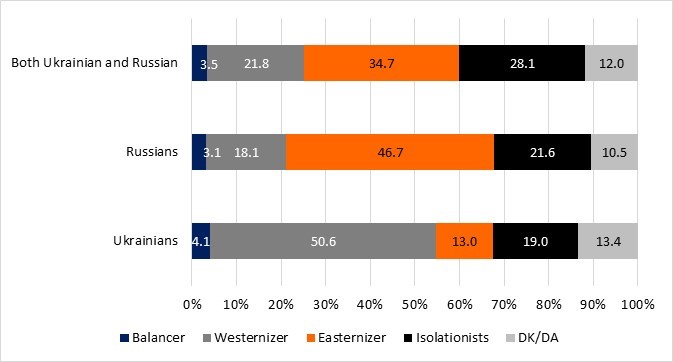

Figure 7. Distribution of geopolitical preferences in each ethnic group, Ukraine (2015-2019).

Ukrainians N=15,474, Russians N=1,073, and both Ukrainian and Russian N=519

Source: Own elaboration based on KIIS Omnibus, 2015-2019. The definition of the nationality variable can be found here. When we control for socioeconomic variables such as age, education level, socioeconomic status, sex, frequent use of the internet, and being a worker or not, there is no difference in the share of balancers between ethnicities. However, even with these variables those identifying themselves as Russians or both Ukrainian and Russian tend to be more Isolationists or Easternizers and less Westernizers than Ukrainians.

When speaking about other predictors of support for the Balancer and Isolationists options, unfortunately, the Ukrainian surveys did not include variables related to political engagement and future migration preferences, thus we could not test these predictors. However, in the case of Georgia and Moldova, the results of my work show that being interested in politics predicts higher support for the Balancer and Westernizer options while the opposite is true for Isolationists. Willing to migrate to an EU country shows a strong correlation with being a Balancer in both Georgia and Moldova, while wanting to migrate to a CIS country also predicts higher support for this option in Georgia.

A few remarks on Balancers and Isolationists

One of the main advantages of the new four-fold categorization of geopolitical preferences is that it portrays a more fine-grained picture of the geopolitical preferences landscape in a context in which these preferences are of notable importance: the Association Agreement countries. As I have shown, the three AA countries show similarities and differences in the distribution of ambivalent geopolitical preferences, with Moldova and Georgia characterized by an equilibrium between Balancers and Isolationists and Ukraine displaying a much larger number of Isolationists than Balancers. These trends are, most probably, a consequence of contextual differences (out of which direct conflict with Russia might be an important part) between the three countries, but only a more in-depth study of the issue could precisely determine the origins of the differences.

All in all, there are a wide arrange of factors that influence being an Isolationist or a Balancer in the AA countries.On the one hand, apart from the variables that have been already mentioned in the previous version, Balancers tend to be younger (in Ukraine), males (in Moldova), and more educated (in Georgia). On the other hand, supporting the Isolationist path is predicted by not using the Internet often (in Moldova and Ukraine), not having higher education (in Georgia and Ukraine), and not having a good economic situation (in Ukraine). More than trying to identify all of these determinants, my work pretended to shed light on two groups of geopolitical orientations that are often neglected by the mainstream discourses. Understanding the reasons behind support for the Balancer and Isolationist options, how these groups interact with Westernizers and Easternizers, as well as the differences between these two categories, is vital in an environment such as the AA countries, in which national politics tend to be heavily geopoliticised.

Considering the importance of the Isolationists and Balancers groups in the AA countries and the importance of socioeconomic variables over these groups, it seems relevant to continue studying the role that economic and social grievances play in shaping geopolitical orientations. Likewise, taking into account the differences between Moldova and Georgia, and Ukraine in the distribution of Isolationists and Balancers, the governments of these three countries should research how and which contextual factors are the source of the larger number of Isolationists in Ukraine and of Balancers in Georgia and Moldova. Getting to know the sources of these differences between countries (and the practical geopolitical differences between Isolationists and Balancers) could help the governments of the AA countries anticipate potential changes in these groups if the contextual factors change. Summarizing, only by further studying Isolationists and Balancers, together with Westernizers and Easternizers, will we be able to truly understand new developments and changes in the balance between the different geopolitical preferences in the AA countries.

References

Buzogány, A. (2019). Europe, Russia, or both? Popular perspectives on overlapping regionalism in the Southern Caucasus. East European Politics, 35 (1), 93-109.

Torres-Adán, Á. (2021). Still winners and losers? Studying public opinion’s geopolitical preferences in the Association Agreement countries (Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine). Post- Soviet Affairs, 37 (4), 362-382.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations