I started a blog earlier this year, the intent of which is to try to predict major developments in post-Soviet space, including of course in Ukraine – so the emphasis is on what I think will happen, not what I want to happen. That’s the spirit of my talk today as well: I’m going to tell you what I think U.S. policy will be toward Ukraine in the remaining years of the Obama presidency, not what I think it should be.

I will focus first on domestic development in the U.S., because domestic political factors inevitably influence a president’s foreign policy. I will then turn to U.S. policy toward Ukraine, beginning with some general points and then addressing the particular issues shown in Slide 1.

Slide 1

The November 2014 congressional elections

In my view, Barack Obama’s primary strategic mission has been to get the U.S. economy going. Although the recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-2009 has been slow and painful, he has been generally successful, albeit with a great deal of help from expansionary monetary policies coming out of the Federal Reserve.

The immediate problem for the president, however, is that the Great Recession was very sharp and painful and the recovery has been a long hard slog. Moreover, although unemployment has steadily declined and is now below 6%, the rate of employment is still low by historical standards, wages have failed pick up, and the great bulk of the gains from the recovery have gone to the wealthy. As a result, wealth and income for many – and probably most – voters is lower than it was before Obama came into office. So in answer to a famous question asked years ago by Ronald Reagan, “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?” most voters are going to say “no.” Americans also feel more insecure, having just witnessed the worst recession since the World War II. It is hardly surprising, then, that the president’s approval ratings are low – according to the latest Rasmussen tracking poll, 47% of likely U.S. voters approve of his job performance. What makes those numbers worse for Democrats running for office this year is that only 23% strongly approve, while 40% strongly disapprove.

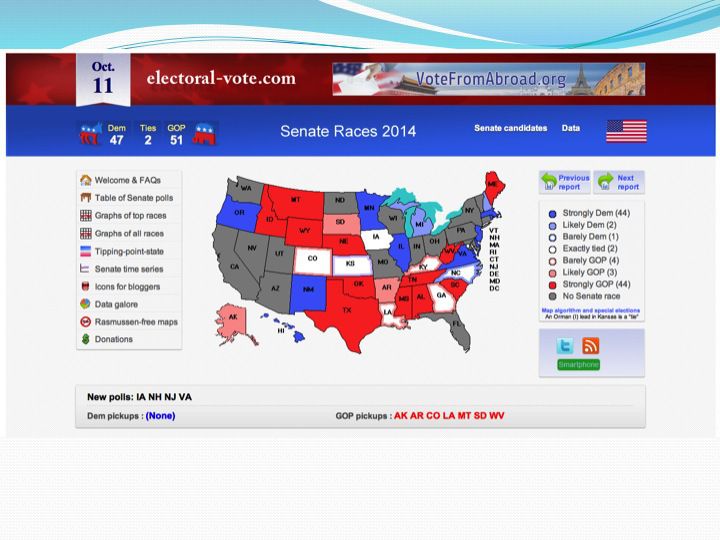

Clearly, then, Obama’s low approval ratings will help Republicans in the upcoming congressional elections. The Republicans will certainly retain control of the House of Representatives and will very likely add a few seats to their current majority, albeit not many. That won’t make much difference politically, however, because the Republicans have a majority in the House already. What would matter more would be if the Democrats lose control of the Senate, which now seems very likely. On-line betting services last week had Republicans as 70% favorites to win control of the Senate in November. They put the probability of a tie at around 10%, which would in practice be a win for the Democrats because the vice president breaks tie votes, and the probability of an outright Democratic majority at around 20%. As Slide 2 suggests, the likelihood is that, unless something unexpected happens, the Republicans will win at least 51 seats, and perhaps a few more.

Slide 2: Probable outcome of November Senate elections

This, I think, is mostly a protest vote. That is, most Americans are unhappy with the state of the country and above all with the weak economy. They have also been getting a lot of bad news recently from abroad, particularly about the rise of the Islamic State and the Ebola epidemic. American presidents, like leaders most everywhere, tend to get the credit when things go well, regardless of whether they deserve the credit, but they also get the blame when things go badly, again regardless of whether they deserve it.

At any rate, it is now very likely the Republicans will control the Senate for the final two years of the Obama presidency. However, I don’t think this will make a great deal of difference politically. The Senate has a rule that in effect means important legislation needs at least 60 votes to pass. Senate Republicans have had more than the 40 votes needed to veto legislation since the Democrats lost their 60-seat majority in 2009. They have also been very disciplined, with few Republican Senators breaking ranks, which is one reason why there has been so much “gridlock” in Washington in recent years. Control of the Senate will mean that Republicans are better positioned to block White House personnel appointments, particularly judicial appointments, and it will increase their ability to pressure the president politically. But the Democrats will retain blocking power – they will have well over the 40 seats need to block legislation if they wish to. And Obama will also have his veto powers.

As a result, the United States will emerge from the coming elections in more-or-less the same political position it has been since the early years of the Obama presidency – divided government, with Democrats and especially Republicans assuming that they will be punished by their electorates if they compromise with the opposition. It is possible, however, that with more power the Republicans will be also be more willing to compromise, which means there is at least a chance we will see some important legislative achievements before Obama leaves office.

Likewise a Republican-controlled Senate will have some impact on foreign policy, but I suspect not a lot. There will be some additional political pressure on the president to be more assertive internationally, particularly in the use of military force. But I doubt Republicans are going to be very assertive in this regard, both because there are more Republicans now than there used to be who are dubious about American foreign policy activism, and because the American public is increasingly skeptical as well.

A Republican Senate probably will have one important effect, however, which is to make it rather more likely that Obama focuses on foreign policy, where he will have more freedom of action, during the remainder of his term.

Changing public foreign policy preferences

As I suggested earlier, the American public is worried about the international environment, and many agree with the president’s Republican critics, and some Democratic critics as well, that his foreign policy has been weak and “feckless.” But the public also tends to support Obama’s caution and pragmatism with respect to particulars, including his reluctance to use force – which is to say, the public, not unusually, generally approves of the president’s policies but not the results of those policies.

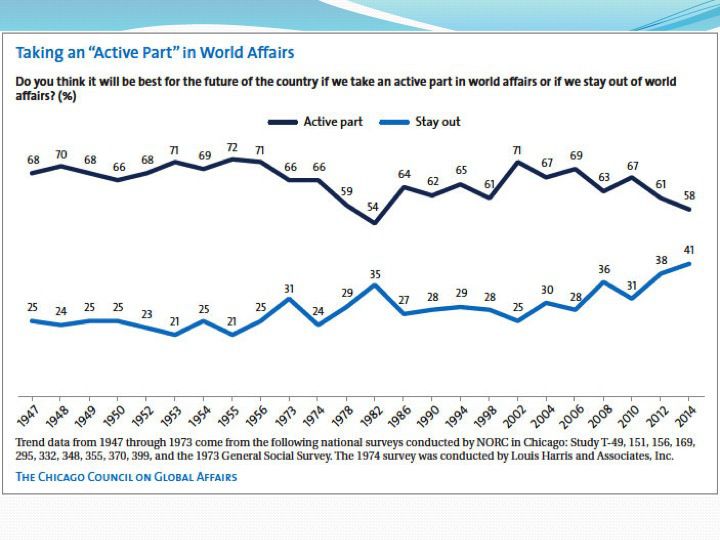

Public skepticism about U.S. foreign policy activism was highlighted in a recent survey by the Chicago Council of Global Affairs. As shown in Slide 3, the percentage of Americans who think the U.S. should take “active part” in world affairs has declined from 71% after September 11 to 58% in 2014.

Slide 3: American public support for foreign policy activism, by year

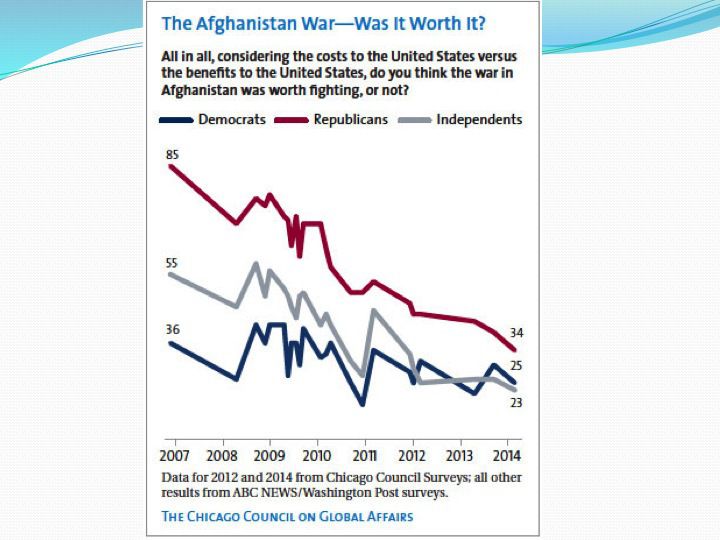

Slide 4 shows support for the war in Afghanistan has also declined dramatically since 2007, and particularly among Republicans – from 85% in 2007 to 35% today.

Slide 4: Public support for the war in Afghanistan, by year and party affiliation

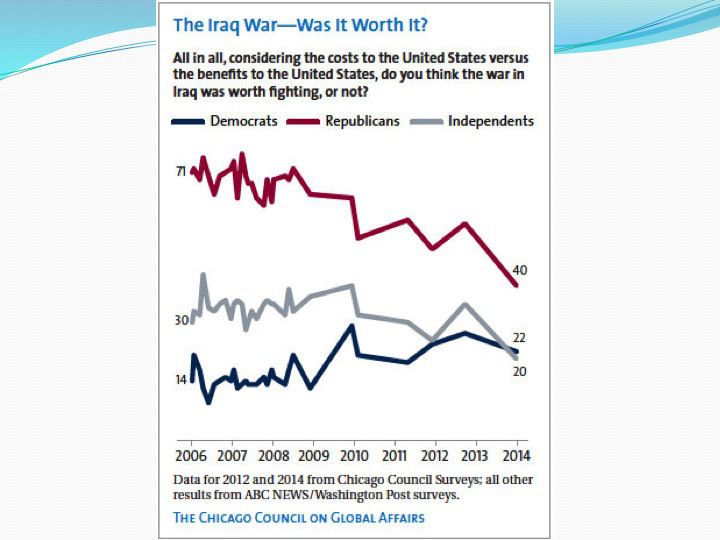

And support for the war in Iraq has also declined, as shown in Slide 5, and again most dramatically among Republicans.

Slide 5: Public support for the war in Iraq

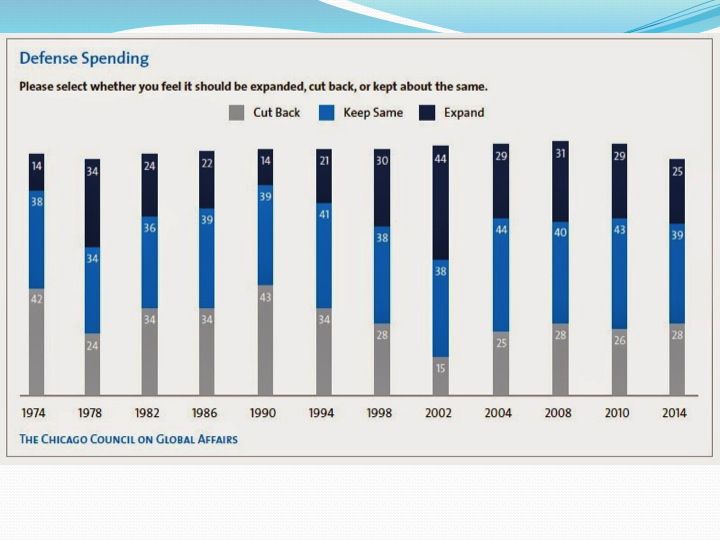

In addition, the public is increasingly skeptical about the need for increased defense spending – in 2002, 44% thought the United States should spend more on defense, with only 15% saying it should spend less; today 25% are in favor of spending more, 28% are in favor of spending less. There is also a sense that United States is spending more the military as a percentage of GDP than its NATO allies, and that there should be more “burden sharing” by Europe, which is being made much less likely in most cases by current economic conditions.

Slide 6: Public support for defense spending

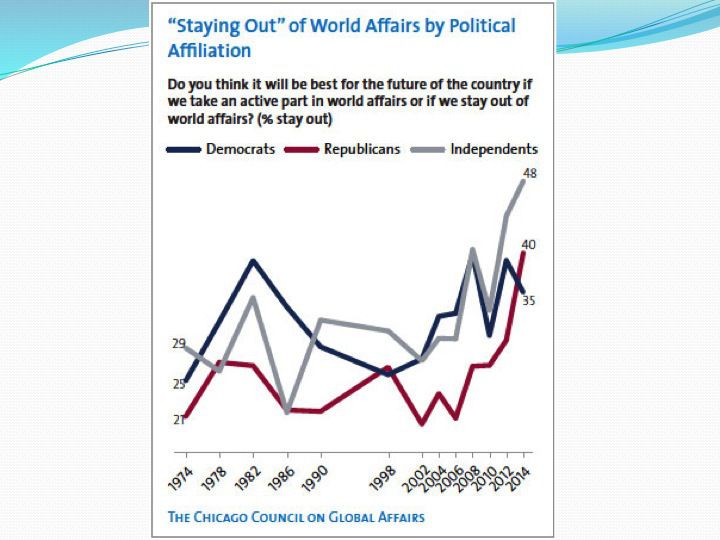

Finally, the next slide suggests that Republicans are now more “isolationist” than Democrats – 40% to 35% who want to the U.S. “stay out of world affairs” – and that independents are more isolationist yet (48%). These numbers would doubtless change somewhat if there were a Republican in the White House, but I suspect they would not change very much. Americans in general, including Republicans, are more skeptical about the efficacy of military intervention and “nation building” than they were before the long and very costly campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.

US economic prospects in 2015 and 2016

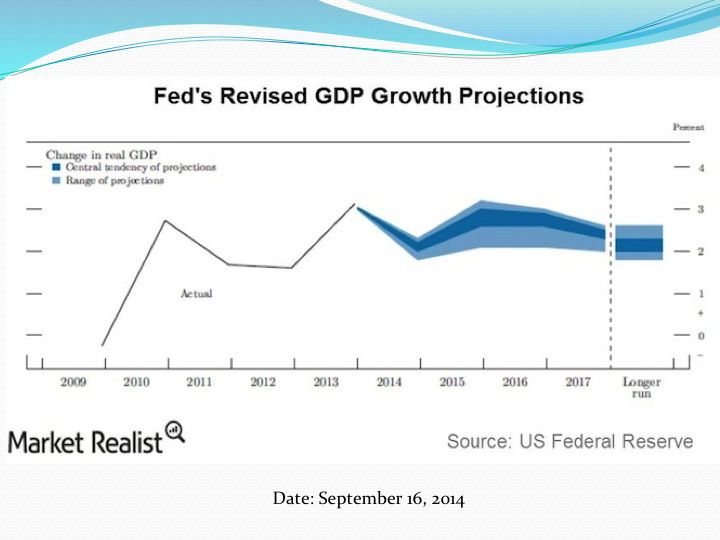

For Obama, nothing is more important to his political capital, and ultimately to his legacy as president, than the economy. The news there has been encouraging. After a rough first quarter, the economy rebounded strongly in the second quarter, and most forecasts have the economy growing at around 3% or a little better in 2015 and 2016. Growth forecasts by the Fed, which are probably a little more pessimistic than average, are shown in the slide below.

Slide 8: The Fed’s GPD forecasts

This improvement in economic performance is coming too late to help the Democrats very much in November, however – there is typically a lag of six months or so before significant changes in economic performance start to have an impact on public opinion. But growth of 3% or more for the next two years will be extremely helpful to the Democrats in the much more important elections scheduled for 2016, which I will discuss in a moment.

It is of course very possible that these forecasts will prove wrong – there have been a number of false starts in recent years. And there are big risks out there, perhaps even more so than the usual – the known unknowns, as well as the usual unknown unknowns. There is considerable concern, for example, about what will happen when the Fed starts tightening, which is generally expected, if the economy continues to show strength, in the summer or fall of next year.

One possibility is that rising interest rates will have an unexpectedly powerful effect in taming the “animal spirits” after the Great Recession. Another is that international investors seeking yield – and safety – will flee emerging market debt, and possibly European debt, and buy up U.S. treasuries, other U.S. debt, American real estate, and other U.S. assets, the effect of which will be to drive up the dollar, choke off exports, import deflation, and create new asset bubbles at home.

In the long run, a rush of hot money into the U.S. may not be a good thing, but I suspect in short run it will help the recovery. It will delay Fed tightening and keep the recovery on track at least through 2016, which will on balance help the Democrats as the party in White House more than the Republicans.

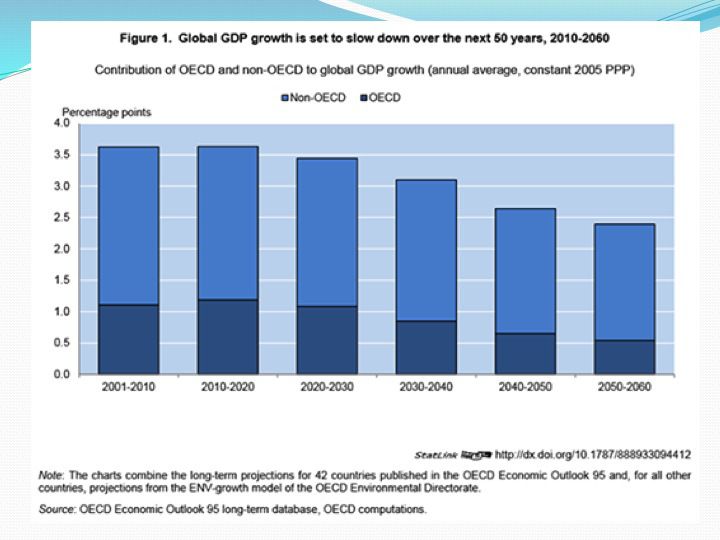

There is another known unknown, which is the health of world economy in general and Europe in particular. Growth in China is slowing, and Japan appears to be back in a low growth rut. But in my view the United State’s most acute geopolitical problem is probably Europe’s growth crisis, and the threat that crisis poses to the entire European project.

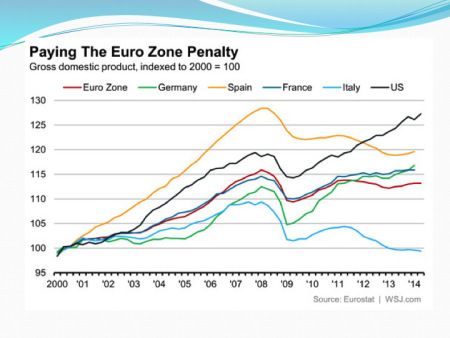

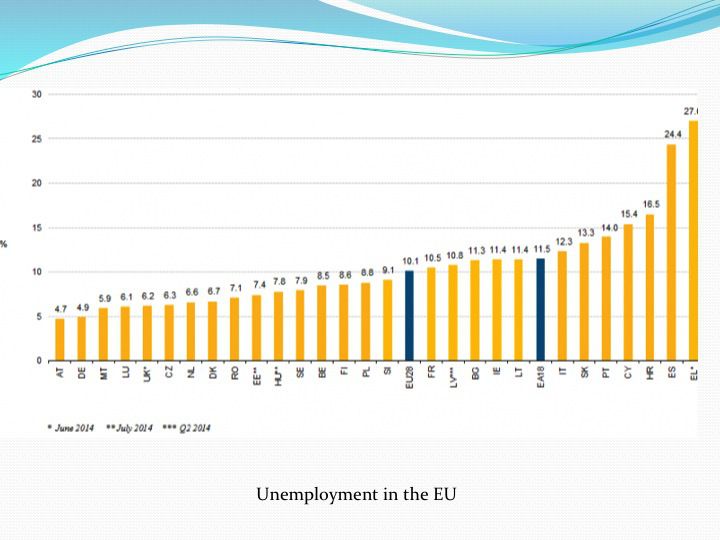

While the US has been recovering slowly and fitfully since 2009, Europe has been essentially stagnated. Total output in some key EU countries has yet to recover to where it was in 2008. Most important politically, however, is Europe’s debilitating and divisive unemployment problem, which as shown in Slide 10, is truly acute. Unemployment in the EU as a whole a little over 10%. But what makes employment so divisive politically is that it is not evenly distributed by country. Unemployment in Greece is 27%, while in Spain it is 24%. In Germany, by contrast, it is around 5%, although that figure masks some “underemployment” – that is, Germany has a lot more part-time workers without full benefits and secure employment than it used to. Moreover, as shown in the next slide, German growth is stalling.

Slide 10: Select Euro zone countries GDP growth

Slide 12: EU unemployment

It is hardly surprising, then, that we are seeing a rapid rise of Euro-skeptic parties across the region, including in Germany, and of anti-system parties on the extreme left and especially the extreme right. One unfortunate impact of the political fallout of economic stagnation is growing opposition to the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), despite that fact that TTIP would help growth in Europe.

Nevertheless, most forecasters think the U.S. economy will manage these problems, particularly given the revolution in energy production in the United States.

The 2016 presidential and congressional elections

If growth does indeed turn out to be 3% or higher in 2015 and 2016, the Democrats will be in a much better position to do well at the ballot box in 2016. That will be especially true if unemployment goes down to 5.2 or 5.3 percent by November 2016, as forecast by the Fed, and if median income and wages start to pick up.

However, two years is a very long time in American politics, so any predictions made now about the elections in November 2016 should be taken with a big grain of salt. But the betting line – which I suspect is a better predictor of electoral outcomes than “expert” political forecasting – has Hillary Clinton at about a 60% favorite to win. No other candidate is given more than a 1/10 chance of winning. Given that there is an outside chance that a candidate other than Hillary Clinton might win the Democratic nomination and then the general elections, the betting line is a little over 60% that a Democratic will win in 2016.

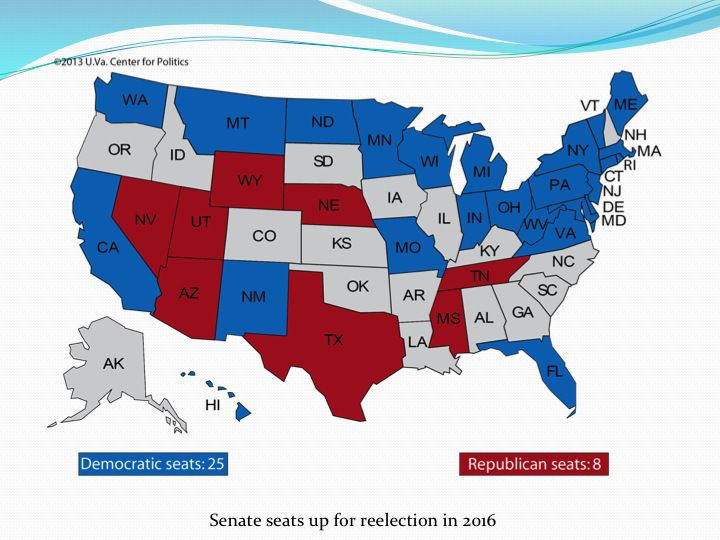

If so, the Democrats are likely to take back the Senate as well, in part because of the so-called presidential “coat-tail effect” but also because the electoral cycle is much more favorable to Democrats in 2016 than in 2014. This year, 25 Democratic seats and 8 Republican seats are being contested. In 2016, it is expected that the numbers will be almost reversed, as shown in the next slide. Democrats will have around 10 seats in play and Republicans 24, as shown in the next slide.

There is also some chance, especially if the economy improves, that the Democrats will win the House in 2016, which would give a new Democratic president the kind of political opening that Obama had in the first years of his presidency. Conversely, a presidential win for the Republicans in 2016 might very well give the Republicans control of all three branches – the presidency, the Senate, and the House – which is why so much is going to be at stake in 2016.

US policy toward Ukraine: Some general points

Now on to US policy toward Ukraine specifically. Let me begin with four igeneral points.

First, if the Republicans take control of the Senate after the November elections, there will be more political pressure on Obama to be tough with the Russians and to help Ukraine, including more pressure to provide Ukraine with lethal weapons. However, because public skepticism about foreign policy activism and risk taking is relatively high, and because there is now a large faction in the Republican Party that is relatively “isolationist,” I do not expect that pressure to be very significant, and I doubt that it will be enough to force the president to take steps he would otherwise not take, except perhaps at the margin.

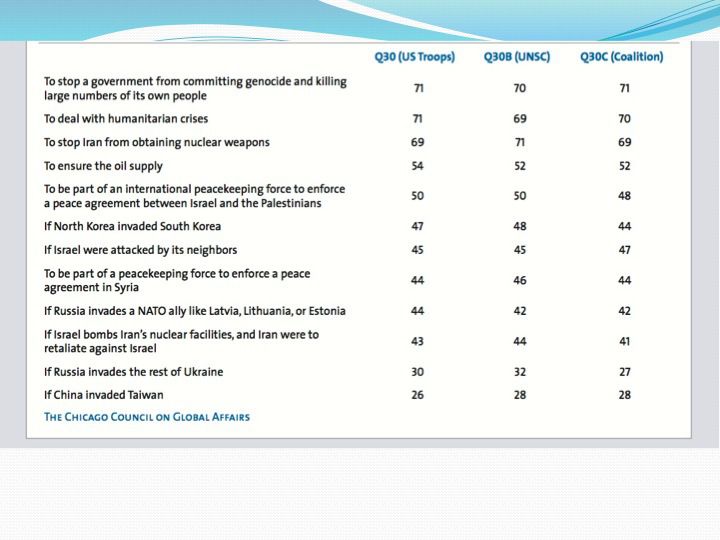

To appreciate why, take a look at next slide, which is from the CCGA survey I discussed earlier.

Slide 13: Public support for military action

It shows public support for U.S. military action, with the first column being unilateral military action, the second being military action with UN Security Council authorization, and the third being military action as part of a coalition. As you can see, support for humanitarian intervention – the first two lines – is quite high. Support for the use force to stop Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons is also relatively high. There is rather less support for using force to ensure the supply oil. Well down the list is support for military action if Russia were to invade the Baltic states, which as you know are NATO members. In fact, I suspect that most Americans are not aware that the Baltic states are our NATO allies, that we are legally obligated, more-or-less, to come to their defense if they are attacked under Article 5 of the NATO treaty, and that these very small states that share borders with Russia are extremely vulnerable militarily. Finally, note that only 30% of Americans support military assistance to Ukraine if Russia invades the rest of the country.

I would not read this as suggesting that the US would not respond militarily if Russia attacked the Baltic states or if it undertook a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In fact, I am sure that the U.S. would respond to attack on the Baltic states (although it is very unclear how it would so, or how robustly, and I am not sure that other key NATO member states, notably Germany, would participate). If Russia were to invade Ukraine full bore, and especially if the invasion got bogged down, I am also quite sure that the United States would step up military assistance to Ukraine, including the provision of lethal weapons. Rather, the point is that there are significant domestic constraints on a stronger response to the Ukraine crisis, and that includes constraints on Republican hawks.

A third general point is that Americans are generally aware that Russia is much more powerful militarily than Ukraine, that Ukraine is in the midst of an economic crisis, and that the country has been very corrupt and poorly governed since independence. As a result, I believe that they will assume that it will not be easy or cheap to help the country resist Russia, recover economically, and improve governance. Moreover, most Americans know very little about Ukraine, and very few are emotionally attached to it (unlike, for example, Israel). In an April 2014 survey (you can find it on The Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog), only 16% of respondents could locate Ukraine on a political map of the world.

Fourth – and this I think is important for Ukrainians to appreciate – there are a lot of very serious, and in some cases acute, foreign policy problems confronting the United States, problems that demand the attention of the president and that compete for media attention other than Ukraine. Iraq, Syria, Iran, ISIS, China, the Euro crisis, the rising of Euro-skepticism, and at the moment the Ebola crisis, are all major problems for American politicians, government officials, and the public.

I will now turn finally to the specific dimensions of American policy toward Ukraine listed in my first slide.

Status of Crimea and Ukraine

I do not believe there is any chance that Western governments, including the United States, will accept the legitimacy of, or recognize, Russia’s annexation of Crimea or the independence of a self-declared “Donetsk People’s Republic,” “Luhansk People’s Republic,” or “Novorossiya.” The annexation of Crimea is, in my view, going to be a particularly serious long-term obstacle to a genuine improvement in relations between the United States and Russia. I think it will be a very long time indeed before we see Russia referred to once again as a “partner” of the United States, NATO, or the EU, let alone as an “ally.”

Economic sanctions on Russia

I think that the great bulk of the sanctions that have been imposed on Russia will remain in place for the foreseeable future. Western governments have taken the position that sanctions will be “reconsidered” if, and only if, Russia changes its behavior, and in particular if it fully implements the terms of the September 5 Minsk Protocol. That, however, is extremely unlikely.

There are at least two key provisions of the Protocol that Russia is very unlikely to deliver on. Provision 4 requires the signatories to “ensure the permanent monitoring of the Ukrainian-Russian border and verification by the OSCE with the creation of security zones in the border regions of Ukraine and the Russian Federation.” Provision 10 requires the withdrawal of “the illegal armed groups, military equipment, as well as fighters and mercenaries from Ukraine” (a requirement that was reiterated in the follow-up memorandum of September 19).

I think there is very little chance that Russia will allow the OSCE to establish and monitor a genuine “security zone” along the Russian-Ukrainian border – that is, one that is not fully open to the passage of military equipment and of irregular and, if need be, regular troops from Russia into Ukraine. I think it is even less likely that we will see a withdrawal of “illegal armed groups, military equipment, as well as fighters and mercenaries from Ukraine.” And that in turn means that it will be very difficult politically for Western governments to lift sanctions even if they want to.

In the U.S. case, I do not believe the Obama administration would lift sanctions, in whole or in part, even if it had a completely free hand. However, if the Republicans take control of the Senate, lifting sanctions will become even less likely. It is important to remember that sanctions would have been imposed on Russia for its occupation and annexation of Crimea alone, and they would have been very difficult to lift even if there had been no war in the Donbas. The Russian-supported war in eastern Ukraine has only made sanctions even more entrenched. Even if Russia complies with the Minsk Protocol fully (as unlikely as that might be), the annexation of Crimea will remain in place.

In short, I think that additional sanctions, should Russia escalate its involvement or invade outright, are more likely than a significant lifting of sanctions.

Economic assistance to Ukraine

Politically it will be difficult for the Obama administration to provide a great deal of economic assistance to Ukraine. The U.S. economy is still at soft, and most Americans feel most foreign assistance is generally wasted. Moreover, Republicans are generally enthusiastic about military assistance – they are notably less enthusiastic about economic assistance. So a Republican-controlled Senate will not change very much in this regard.

Accordingly, I expect more of what we have witnessed to date with respect to American non-military assistance to Ukraine. There will very likely be an increase in USAID funding for Ukraine, Washington will contribute to new international assistance packages; it will continue to support conditional multilateral assistance through the IMF; it may agree to guarantee some IMF loans; and it may support efforts to debt rescheduling or relief.

This assistance will be very important to Ukraine, and without it the country’s economic travails going forward would be a good deal worse. However, the important point is that assistance from Washington, the EU, other Western governments, and the IMF and World Bank is not going to prevent at least several years of economic hardship for Ukraine. And in the longer run, overwhelmingly the most important factor determining whether Ukraine will start to catch up economically with Poland and the rest of Europe will be the success or failure of its internal economic and political reform efforts. That was true in 1992, and it is no less true today. In the meantime, the costs of “transition” are going to be very high, and it is likely that the Ukrainian public will consider the extent of foreign and U.S. assistance inadequate.

EU accession

The Obama Administration will certainly support Ukraine’s EU accession process. However, Washington cannot to be too heavy-handed in trying to influence the EU on internal matters — doing so can be entirely counterproductive. So Washington’s support here probably won’t matter very much. But as it stands now, I think the EU leadership is in any case serious about seeing the Association Agreement implemented, and Russia’s intervention has made it more determined to accept Ukraine as an EU member at some point. That, however, will take years under the best of circumstances. It will take longer if Ukraine reform efforts disappoint, or if Euro-skeptics become politically more powerful. If Ukraine’s reforms fail, or if the European project really comes to halt, it may never happen.

Non-lethal military assistance to Ukraine

I am sure that the current commitment by the United States to provide non-lethal equipment and military training to Ukraine will continue, and indeed non-lethal assistance program will probably have bipartisan support in Congress. That includes in particular the help with secure communications and reconnaissance drones.

However, the administration is probably going to be careful about crossing the provocation line – that is, it is going to be wary about provoking Russia into escalating its military pressure on Ukraine or elsewhere. It is also going to be wary of following in the footsteps of the previous administration in Georgia, where U.S. military assistance to Tbilisi may have encouraged Georgian President Saakashvili to take actions that contributed to the Russian invasion in 2008.

I expect the same for American intelligence assistance to Ukraine. Of course I don’t know how extensive that assistance has been, but I suspect it has been extensive and will continue be extensive. The caveat is that U.S. intelligence agencies will worry about Russian penetration of Ukraine security services, so they will be careful about potential compromises of human or national technical assets.

Lethal military assistance to Ukraine

I think Republicans gains in the upcoming elections is going to result in increased political pressure on the Administration to provide “lethal” military assistance to Ukraine, particularly “defensive” equipment such as anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons. Already there are many in Washington, including many Democrats, who are making the argument.

However, I also believe that the Obama Administration will resist these pressures, at least until it is reasonably confident that Ukraine is better able to defend itself against a Russian invasion. Again, the reason is that it does not want to cross the provocation line.

In my view, if the U.S. governing elite was as cynical as most Russians seem to think it is, and if it were truly intent on humiliating Russia, weakening it, fomenting a “colored revolution,” and seeing it break apart, it would deliberately provoke a full-blown war between Ukraine and Russia. One way to do so would be to dramatically increase military assistance to Kyiv, including the provision of all forms of lethal assistance. In particular, it would provide Kyiv with the kinds of weapons that would best sustain partisan resistance to foreign intervention.

If Russian then invaded and tried to occupy very much of Ukraine, the conflict would be extremely destructive, but I am also very sure that Russia would eventually lose that war. As Americans are now well aware, invading, occupying, and pacifying a foreign country is extremely difficult and costly. Ukraine is a very large country, with a great many urban areas that would be ideal for partisan resistance. There are also clearly a great many Ukrainians who would fiercely resist foreign invasion and occupation. Indeed, I suspect that Ukrainians would fight every bit as hard to defend Ukraine as Russians would fight to defend Russia. I likewise suspect that the Russian public would quickly conclude that invading, occupying, and pacifying Ukraine was morally reprehensible and enormously costly, which would greatly increase the likelihood that the country would, in fact, experience some kind of “colored revolution.”

For the most part, however, the American political elite is not that cynical. It is also far too risk averse to believe that this would be a good idea. The Obama Administration in particular has no desire to provoke a full-scale war between Russia and Ukraine. In part the reason is that it believes, like most Americans, that the result would be humanitarian catastrophe. But it also doubtless thinks that Russia would prevail on the battlefield, at least initially, and that there is also a risk the war would spin out of control and lead to a direct military clash with NATO. There is a risk that the Russian response would be limited to establishing a land corridor to Crimea, which is a much less ambitious military objective than trying to occupy very much of eastern or southern Ukraine, let alone anything west of the Dnieper.

And then there is an even more dangerous risk for the West, which is that going too far in Ukraine could lead Russia to attack where NATO is most vulnerable, which is in the Baltic states. The essential problem for the West from the outset this conflict has been that Russia not only has a great preponderance of force along its borders, it also has a strategic nuclear arsenal that could destroy the United States and Europe, as well as thousands of tactical and battlefield nuclear weapons. Despite the fact that the United States alone, and even more the U.S. together with its Western allies, dwarf Russia both in economic and in conventional military power, it is nonetheless unclear that the West could dislodge Russia from territory it has seized militarily. If it were simply a matter of conventional hard power, and if the West were truly committed to such an effort, it would eventually prevail, but only at tremendous cost. But the risk is that, rather than accepting a conventional defeat, Russia would walk up the ladder of escalation and resort to battlefield nuclear weapons.

That fact is, although they are NATO member-states, the Baltic republics are very small countries with very small populations, which also border on Russia (Lithuania albeit on Kaliningrad, not mainland Russia). They also, at least for now, have almost no ability to defend themselves – Ukraine, by comparison, is a much more formidable military opponent for Moscow. There is now a very small NATO footprint in the Baltic republics, in the form of a rotational aviation and a naval presence, but no real troops on the ground. NATO planners, and the Obama Administration, accordingly have to consider the possibility that Russia would invade the Baltic republics, or perhaps just Latvia and Estonia, and then dare NATO members to try to dislodge it, knowing full well that Russia’s declared position is that it will resort to nuclear weapons if it feels the need to.

That, in short, is the most important reason why the military tensions between the NATO and Russia are so dangerous (although there are other reasons). And it is also why the Obama Administration is going to be very careful not to cross the provocation line.

NATO accession

These same constraints and risks also explain why Washington is even less likely to push for NATO accession for Ukraine – it is now clear that Russia’s “redline” is NATO accession for Ukraine and Georgia. But there are at least two additional reasons that warrant mention, both of which are legal in nature.

First, there is the question of what the country is that would be joining NATO. Given that the West is committed to Ukraine’s territorial integrity, Ukraine joining NATO would mean that the Crimea and the Donbas would be part of the territory that NATO members are committed to defending collectively. If Ukraine invoked Article 5, the rest of NATO would be legally bound to provide Ukraine the assistance needed to restore Ukraine’s sovereignty, which effectively put NATO at war with a nuclear superpower and the world’s second most powerful conventional military. That is not something NATO countries are willing to contemplate, for obvious reasons.

Second, NATO is a treaty alliance of democratic states, and taking in new member requires an amendment to the NATO Founding Act. That in turn means that every single NATO member has to agree to, and ratify, the accession of new members. I do not believe there is any chance that Hungary, Italy, Bulgaria, or for that matter Germany and France would agree to, and ratify, membership for Ukraine under current circumstances. In fact, there is almost no chance that the U.S. Senate, regardless of the outcome next month, would ratify Ukraine’s NATO accession if it came to it – treaty amendments, like treaties, require approval by a 2/3 majority in the Senate.

De-escalation of military tensions with Russia

I think the big story over the coming two years in US-Russian relations is going to be in the military sphere. I believe that the military tensions with Russia in a variety of arena – in Ukraine of course, but elsewhere along Russia’s western borders as well, in the Baltic and Black Seas, in the Arctic, in the Far East, and possible elsewhere – are very dangerous, and there is a not insignificant risk that they could lead to a military clash, one that might in turn escalate into a catastrophe.

Accordingly, I think at some point we are going to see both sides decide it is better to negotiate to reduce those tensions, much as the West and the Soviet Union decided they should try to reduce tensions in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The eventual outcome was détente, a host of arms control treaties, and the Helsinki Accords of 1975. With luck, the United States and its NATO allies will come to an agreement with Russia over new rules in political and especially military arenas that will make what is very likely to be a long geopolitical struggle less costly and less dangerous. I think the Obama administration probably realizes this as well, and if things do not get worse in Ukraine or elsewhere, it will probably approach Moscow quietly at some point over the next two years to see if Moscow is receptive to, for example, discussions over a new Conventional Forces in Europe agreement. I am not at all confident that Moscow would respond favorably, but it might.

Note: This post is an expanded version of a talk given at the VoxUkraine club & Kyiv School of Economics on October 23, 2014. This is a repost of Prof. Walker’s blog.

The whole presentation you may find here: US_policy_towards_Ukraine.ppt

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations