In 2022 and 2023, we surveyed Ukrainians asking about their perception of reforms and their civic activity. This year, we performed a similar survey to see whether the perceived importance of reforms by our compatriots changed. Are they more or less involved in civic activity? What reforms do they expect most and are they ready to cope with some inconveniences during the transition period? What are the greatest obstacles and the most expected results of reforms?

The main results

- Ranking of reforms by importance between 2022 and 2024 is practically unchanged: digitalization, army reform, healthcare, and anticorruption are still the top four.

- Anticorruption measures are the most expected reforms in 2025. In line with this, reduction of corruption is the most expected result of reforms, with increase in welfare in the second place. In 2022 anticorruption and welfare increase were at the top too but the difference between them was smaller.

- Today Ukrainians believe that the largest obstacle to reform is lack of political will, with the second obstacle being counteraction of vested interests. In 2022 counteraction of vested interests was the top obstacle, while lack of political will occupied the second place. Inaction of citizens in 2024 moved to the third place from the fifth place in 2022.

- 37% of respondents believe that public servants should get salaries close to the market level, 42% – at Ukrainian average level, and only 21% believe that they should be paid minimum wage.

- Ukrainians are able to determine which actions are corrupt and which are not quite well.

- The most common civic activities in which citizens are involved today are donations (64%), signing petitions (44%), and volunteering (34%) – the same as in 2022.

- People who donate and those planning to join an NGO or become a volunteer are more likely to recognize the importance of practically all the reforms. Those who participate in government meetings or meetings of their communities are more likely to name decentralization and digitalization important.

- People who know about the content of the IMF program or Ukraine Facility plan, as well as those who believe that public servants should get salaries close to the market level, are more likely to recognize the importance of the majority of reforms (perhaps these people are generally more interested in politics and social issues). Being in a low-income group decreases the probability that a person recognizes the importance of some reforms (education, tax, healthcare, decentralization) and is insignificant for others.

- Expected reform results and opinions on the major obstacles to reforms are correlated with prioritization of reforms for 2025. For example, people who believe that reforms should result in higher effectiveness of public spending are more likely to prioritize tax reform, and those who believe that reforms should result in higher life expectancy are more likely to prioritize education and healthcare reforms.

- People who think that some reform is important or beneficial for society are more likely to prioritize this reform for 2025. We find practically no cross-effects for reforms for which we did not ask about importance or social benefits (customs, pension reforms, and EU integration). For them, expected reform results and obstacles to reforms are more significant.

- Descriptive statistics

- What do Ukrainians think about reforms?

- Can Ukrainians identify corruption?

- What do Ukrainians think of salaries of public servants?

- News sources

- Participation in civic activities

- Factors that impact perception of the importance and social impact of reforms

- Factors that determine 2025 reform priorities

- Conclusions and policy implications

Data description

The survey was fielded in September 2024 by InfoSapiens, a survey/marketing company, using an online panel with over 50 thousand participants. The sample includes 3,090 respondents over 18 years old, the sample structure is consistent with the structure of the Ukrainian population as of January 2022. IDPs in the sample are slightly overrepresented: their share is 14% whereas the current number of IDPs older than 18 in Ukraine is about 2,2 million representing 7% of the pre-war population of this age in the government-controlled areas. The share of refugees in the sample – 4% – is lower than in the population: there are about 4.5 million Ukrainian adults who live abroad, which is 15% of population 18+ in government-controlled areas in 2021. The reason may be that some Ukrainian refugees no longer have Ukrainian phone numbers and thus cannot be included into the panel.

Descriptive statistics

47% of respondents are male, 58% are married and 24% are single (the rest are divorced or widowed), 53% don’t have children under 18, 27% have one child, 13% two children, and the rest have more. 71% of respondents never left their place of living, 12% relocated after February 24th 2022 but returned by the time of the survey, 14% relocated within oblast or moved to another oblast (mostly from Eastern and Southern regions), and about 4% now live abroad. The majority of refugees and IDPs are willing to return, although not in the nearest future (figure 1). For analysis, we use regions and types of settlements where respondents lived before February 24th, 2022 because if regional variables have some effect (which we don’t expect), this effect will likely be caused by the place where a person lived longer. The regional distribution of people before and after full-scale invasion is quite similar (table A1 in the Annex).

Figure 1. Do you plan to return? (answers of IDPs and refugees)

58% of respondents are employed (of them 59% work in the private sector, 9% in NGOs and the rest work in the public sector), 15% are unemployed, 3% serve in the army. 50% of the sample have higher education, 29% - professional, and 19.5% - secondary education.

The relative majority (46%) of our respondents are not extremely poor: they can buy food and clothes but have difficulty buying durable goods (figure 2). Expectedly, the majority of people report that their material stance worsened because of the war.

Figure 2. Distribution of respondents by income groups and changes in material stance after the full-scale invasion

Note: the figure shows percentages of total sample; colors show the answers to the question “How did the material stance of your household change after 24.02.2022?”

What do Ukrainians think about reforms?

Current opinions on reform importance are very similar to 2022. Reforms of the army, digitalization, anticorruption, and healthcare remain the top four, although in a slightly different order. Judicial reform, tax reform and small privatization are perceived as less important (figure 3).

This year, we also asked the respondents about the effect of reforms on the society (figure 5), i.e. whether they think that the society as a whole won or lost from the major reforms. We make this distinction because although a reform may be important, some social groups may lose from it, e.g. those who used to evade taxes will not be happy about tax administration reform. Figures 3 and 5 are very similar, and the correlation between importance of a reform and its perceived benefit for the society is positive (although never higher than 0.5).

We also see a much higher share of “don’t know” answers to the question on social gain from reforms than on importance of reforms, which suggests that more communication of reforms is needed, specifically on pros and cons of reforms for different social groups.

Figure 3. Please evaluate the importance of reforms

Note: the data are sorted by the sum of “very important” and “rather important”

Figure 4. Comparison of importance of reforms in 2022 and 2024 surveys

Note: reform score is calculated as a weighted average of answers to the question “How important is a certain reform?” with 4=very important, 3=somewhat important, 2=rather not important, 1=not at all important, and 0=never heard about it.

For each of the reforms their “importance score” is lower today than it was in 2022 (figure 4). Perhaps in 2022 people believed that reforms would quickly increase the resilience of the country. To the open question on important reforms not listed in the survey, about 2% of respondents wrote about the need for a change in government (implying not only elections but also altering responsibilities of president and parliament, reducing the number of MPs etc.). About 1% of respondents mentioned that reforms are useless and about the same share - that they are not implemented properly and thus “ordinary people” do not feel their effect. A similar share of respondents mentioned that entering NATO is important, while very few wrote about either winning or ending the war (note that these results cannot be extended to the entire population since people may have self-selected into answering open questions).

Figure 5. When reforms are implemented, some citizens and enterprises win and some lose. In your view, the society as a whole has won or lost from the following reforms?

Note: the figure is sorted by the sum of “definitely won” and “rather won” answers

Among the reforms which respondents expect in 2025 (figure 6) anticorruption is a clear leader. This is no surprise because the most expected result of reforms is reduction of corruption (figure 7). Consistently with this, Ukrainians view the lack of political will (61%) and counteraction of vested interests (50%) as major obstacles to reforms (figure 8), and 2% specified “corruption” as their “other” option in this question. Note that in 2022 “counteraction of vested interests” was in the first place (64%), while “lack of political will” was second with 52%. The fact that in 2024 “political will” is in the first place may signal that today Ukrainians put more responsibility for slow implementation of reforms on the government.

A much larger focus on corruption today than in 2022 may be the result of a number of corruption scandals which rocked Ukraine recently. This, of course, does not imply that journalists should stop uncovering corruption. Rather, the government should implement (and communicate!) respective reforms.

Another notable change is that this year “higher impact of citizens on government decisions” is in the third place of expected reform results (it was fourth in 2022). This is consistent with the third place of “passivity of citizens” as an obstacle to reforms, up from the fifth place in 2022. This suggests that citizens recognize their responsibility for changes in Ukraine and probably are more willing to participate in changes. Thus, the government and media could provide information on available instruments of citizen participation.

Figure 6. Which reforms should be implemented in the first place in 2025? (no more than three answers)

Figure 7. Expected reform results

Note: respondents could select up to 3 answers as well as provide their own. In 2022, this question had an additional option “higher GDP” which was selected by 31% of respondents.

Figure 8. What are the major obstacles to reforms?

Note: respondents could select up to 2 answers as well as provide their own. The answer “corruption” is derived from “own” answers. In 2022, respondents could select three answers, thus, one need to compare only the ranking of alternatives rather than shares of respondents who selected them.

We asked our respondents whether they know the major programs - the Ukraine Facility plan and the IMF program - listing reforms which the Ukrainian government promised to implement. The majority of people either don’t know anything about these documents or have heard something about them (which is also low awareness). About a fifth of respondents know the content of these documents from the media, while only 4-5% read the documents (figure 9).

Figure 9. Are you aware of these documents?

Compared to 2022, today respondents are less willing to cope with material or organizational hardships associated with reforms (figure 10). Perhaps this is also a sign of exhaustion of the “rally around the flag” enthusiasm. Publications on the progress of reforms and how they impact our lives could support popular understanding of the need for them. For example, the Ukrainian banking system would not be able to relatively easily cope with the full-scale invasion without some painful moments during the banking sector clean-up in 2014-2015.

Figure 10. Introduction of reforms may be accompanied by material or organizational hardships until the new rules are fully implemented. Are you ready to cope with these hardships?

Can Ukrainians identify corruption?

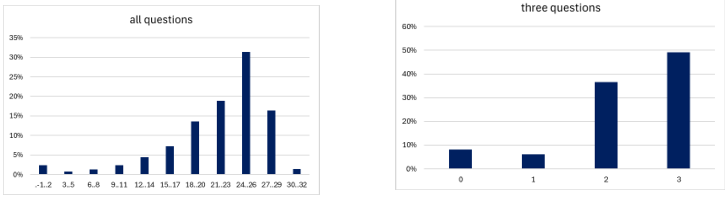

We asked a set of questions to determine “corruption awareness” of respondents. Respondents classified 19 hypothetical situations as “corruption”, “not a good thing to do but not corruption", “it’s ok to do this” or “depending on the circumstances”. Answers to these questions are presented in figure 11. From these answers we constructed two corruption awareness indices. The first one takes into account all the answers (see Table A2 in the Annex for details) and ranges from -1 to 32 (mean 22, median 23) with a theoretical range from -4 to +38.

The second one takes into account only three questions with the most obvious answers - on bribery, on kickbacks, and on taking one’s relative into a subordinate position (nepotism). People who identify these situations as corruption get 1 point for each correct answer, so this index ranges from 0 to 3. Correlation coefficient between these indices is 0.75 thus we use them separately for regressions.

Figure 11. In your view, are the following actions of central or local government officials corruption or not?

Note: “c” means corruption, “n” - not a good deed but not corruption, “d” - depends on additional circumstances, “ok” - not corruption.

What do Ukrainians think of salaries of public servants?

One issue that is often discussed in relation to corruption is the salaries of public servants. Some people believe that low salaries of government servants will make them “feel the pain of ordinary citizens” and thus work harder. In line with this thinking, the Ukrainian government used to limit salaries of public officials during crises in order to satisfy popular aspirations for justice as they see it. However, such populistic moves may discourage highly qualified people from working in the government (and inefficient government is costlier than highly paid government).

To see whether low salaries of officials are popular with people, we asked our respondents, which salaries, in their view, should public servants get. To our surprise, the share of people who think that the salary for public servants should be close to market level (37%) is much higher than those who believe that they should survive on minimal salary (21%). However, 42% still believe that public servants should get average salaries (figure 12). About a dozen of 3090 respondents commented that salaries of public servants should depend on the results of their work.

Certainly, decent salaries are not a sufficient condition for high-quality public service but they should be a part of a larger public service reform. As we see it, Ukrainian society is not aspiring for “poor and hungry” public servants.

News sources

Consistently with other surveys (e.g. Internews), Ukrainians mostly acquire information from social media and online media with only about a quarter using TV (figure 13). Among social media, Telegram is most widely used - by over 60% of people (figure 14). Taking into account its Russian origin, this is a problem, and the government should intensify its effort of moving at least official communications from Telegram to other platforms.

Figure 13. From which sources do you get the news? (maximum two answers)

Figure 14. Which social media do you mainly use? (maximum two answers)

Participation in civic activities

The majority of people never participated and do not plan to participate in NGOs, protests, government activities or creation of petitions (figure 15). The most popular civic activities are donations (64% of people make them) and signing petitions (44%). 34% of respondents volunteer for the army or for other causes. Figures for 2022 are practically the same.

For all the activities except for donations and volunteering the share of people who plan to be involved in them is higher than of people who are involved in them today or were involved during the full-scale war. This doesn’t mean that everyone who has such plans will actually participate in these activities but this suggests that people view these activities as useful. Overall, only 8% of people have never taken part in any of the listed activities and do not plan to do this in the future.

Figure 15. Participation of respondents in different civic activities

Note: numbers in parentheses show the shares of people who participate in certain activities at the moment (e.g. 63.5% donate and 34.3% volunteer). Rows add to 100%.

Figure 16. Share of respondents (%) who participated in some civic activities at the time of the survey, 2022 and 2024

Participation in elections is much higher than participation in other civic activities (table 1). 62.5% of our respondents participated in all or almost all elections, 70% plan to participate in elections in the future. 57% of respondents both participated in elections previously and plan to vote when it becomes possible.

Table 1. Participation in elections and plans to participate in elections when it becomes possible

| ← plans to participate → | |||||||

| previous participation ↓ | yes, in all of them | only in central | only in local | no | don't know | refuse | sum previous |

| in all or almost all elections since I turned 18 | 56.9% | 2.2% | 0.2% | 1.8% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 62.5% |

| only in central-level elections | 5.1% | 4.4% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 11.2% |

| only in local elections | 1.8% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4.0% |

| very rarely | 3.2% | 2.6% | 1.2% | 3.3% | 0.2% | 0.9% | 11.3% |

| never | 1.1% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 0.6% | 7.2% |

| there were no elections since I turned 18 | 2.1% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 3.9% |

| sum plans | 70.1% | 11.5% | 3.5% | 11.1% | 1.1% | 2.6% | |

Note: rows show previous participation in elections, columns - participation plans

Factors that impact perception of the importance and social impact of reforms

Our main question of interest was whether civic participation of a person affects their perception of the importance of reforms. Thus, we estimated (with Probit regressions) how participation in civic activities affects the probability that a person considers some reform “very important” or “rather important”. Similar estimates were performed for the probability that a person believes that the society “definitely won” or “rather won” from certain reforms. We included demographic factors, employment variables, and news sources into regressions.

Participation in an NGO is not significantly correlated with the probability that a person considers certain reforms important or beneficial for society. At the same time people who only plan to join an NGO are more likely to identify as important tax, education, army reform, as well as judicial reform, reforms of state-owned enterprises and public service. Similarly, current volunteers are not significantly more likely to identify any reform as important, while those who only plan to volunteer are more likely to believe that 5 of 13 reforms of which we asked are important (education, digitalization, army reform, land market, and small privatization). Perhaps these people are in general more interested in politics.

Those who are involved in law development are less likely to believe that tax, education, and public procurement reforms are important - these people may be more interested in other reforms. People who send enquiries to government agencies with higher probability think that judicial reform is important (these people may be more aware about the importance of law enforcement).

People who used to be involved in government meetings, as well as those who now participate in meetings of their communities, are more likely to think that society won from digitalization and decentralization. These reforms may have enabled their participation in these activities in the first place.

People who donate are more likely to consider important 8 of 13 reforms about which we asked (this variable is not significant for healthcare, procurement and three “least popular” reforms - judicial, SOE, and public service). These people are also more likely to think that Ukraine won from education, healthcare, procurement, army, and public service reform, as well as digitalization.

Respondents who believe that the salary of public servants should be close to market level, and in many instances also those who think that it should be at Ukraine's average level are more likely to view all the reforms as important (compared to those who suggest that public servants should receive minimum salary). They are also more likely to state that society won from all the reforms. People who can correctly classify more situations as corruption are more likely to view almost all the reforms as significant (although coefficients are very small). We can interpret this result as higher awareness of how the government works and who is responsible for implementation of reforms.

Those who plan to participate in elections are more likely to admit the importance of all the reforms compared to those who would not participate, and identify 8 of 13 reforms as beneficial for society. Previous participation in elections is almost never significant (again, this may be explained by higher interest of these people in politics).

People whose major news source is TV have higher probability of marking all reforms as important and beneficial for society compared to those who mostly rely on friends/relatives or do not follow the news at all. At the same time those who get the news mostly from radio (these may be either people who live in remote locations or those who travel a lot) are more likely than TV viewers to state the importance of education reform. Those who mostly use social media as their news source are more likely than TV viewers to name digitalization both important and beneficial for society.

Expectedly people who know about the content of Ukraine Facility plan or the IMF program (the correlation between these variables is 0.58 so we included them interchangeably into regressions) are more likely to believe that practically all the reforms are beneficial for society than people who have heard or never heard about these documents. For some reforms these variables are insignificant or marginally significant but they are never negative. This suggests that more knowledge about the reforms which are needed for Ukraine’s stable development and EU integration leads to a more positive view on reforms.

Lower-income people are less likely to care about tax reform, decentralization, and land market, whereas the lowest-income group is less likely to also name education, healthcare, and army reforms as important. These people, however, place more importance on anti-corruption.

Employment status (see table A3 in the Annex for details) has practically no association with a person’s probability to mark a reform as important or beneficial for society. Self-employed people and working students are more likely to endorse tax reform, while employees, self-employed, and working pensioners are more likely to believe that public procurement reform is important.

As expected, regional variables are rarely significant. However, people from larger cities and from Kyiv are more likely to believe that healthcare reform is important than villagers and people of other regions - probably because they felt the effect of this reform more. Refugees care less than people who live in Ukraine about tax reform, while IDPs are more likely to believe that society won from healthcare reform.

Having children is positive and significant only for the importance of education reform. This reform is also more important for people under 35, those with secondary education, and for women - probably these are people who are either studying themselves or care about the studies of their children.

People with higher education are more likely to say that healthcare reform is important and that the society won from small privatization and SOE reforms.

Interestingly, gender is significant for the importance and social benefit of many reforms. Thus, men put less importance on education, healthcare reform and digitalization (perhaps because caring about education and healthcare of household members is still mostly women’s responsibility). They are less likely to believe that tax reform and decentralization are important but more likely to say that society won from them.

Factors that determine 2025 reform priorities

Respondents could name up to 3 reforms that are, in their view, most important for implementation in 2025 (see figure 6). This choice can be determined by several factors: perceived importance and social benefit of reforms, reform results which a person considers most desirable, or a person may believe that it is most important to implement reforms that lag behind. Thus, we include into regressions reforms’ importance and social benefit, as well as expected results and obstacles to reforms along with other factors considered above. For all the reforms except for tax and education either their perceived importance or social benefit are positively related to the probability that a person names them a priority for 2025.

Expected reform results and perceived obstacles to reforms are also important for a person’s choice of reform priorities for 2025 (table 2). For example, a person who expects that reforms should increase effectiveness of government spending is more likely to name tax reform as 2025 priority; someone who believes that reforms should lead to increased life expectancy is more likely to name education and healthcare reforms a priority for 2025; and those who expect reforms to lower corruption are more likely to prioritize anti-corruption reforms but also army and judicial reforms (one explanation may be that they believe corruption in these spheres to be especially harmful).

Similar results hold for obstacles to reforms. For example, someone who believes that corruption and counteraction of vested interests are major reform stumbling blocks is more likely to name anticorruption as reform priority, while someone who thinks that lack of knowledge (expertise) is an important obstacle to reform will more likely prioritize education and healthcare.

Table 2. Impact of expected reform results and obstacles to reforms on the probability that a person names particular reform a priority for 2025 (marginal effects)

| tax | education | healthcare | digitalization | decentralization | anticorruption | procurement | army | privatization | judicial | |

| reform results | ||||||||||

| more effective use of taxpayers' money | 0.048 | -0.016 | -0.010 | 0.023 | 0.019 | 0.034 | 0.002 | 0.028 | 0.007 | 0.031 |

| more opportunities for citizens to impact government decision | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.036 | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.047 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 0.011 | 0.000 |

| higher welfare of Ukrainians | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.059 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.004 | -0.018 | 0.023 | 0.000 | -0.018 |

| higher life satisfaction of Ukrainians | 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.030 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 0.064 | -0.011 | -0.009 | -0.010 | -0.016 |

| higher life expectancy of Ukrainians | 0.002 | 0.082 | 0.118 | 0.017 | 0.008 | -0.031 | 0.005 | 0.000 | -0.001 | -0.005 |

| lower corruption | -0.035 | -0.015 | -0.026 | 0.011 | -0.009 | 0.244 | 0.000 | 0.042 | -0.008 | 0.068 |

| obstacles to reforms | ||||||||||

| lack of money | 0.003 | 0.019 | 0.065 | -0.003 | -0.009 | -0.009 | 0.010 | 0.081 | 0.007 | 0.004 |

| lack of knowledge | 0.009 | 0.063 | 0.067 | -0.018 | 0.017 | 0.029 | 0.015 | 0.019 | -0.006 | 0.012 |

| lack of political will | 0.016 | -0.006 | 0.044 | -0.033 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.011 | 0.064 | 0.003 | 0.039 |

| counteraction of vested interests | 0.027 | -0.024 | 0.022 | -0.016 | -0.013 | 0.068 | 0.017 | 0.056 | -0.019 | 0.029 |

| passivity of citizens | 0.026 | 0.017 | 0.068 | -0.011 | 0.002 | 0.010 | -0.003 | 0.071 | 0.010 | 0.011 |

| corruption | 0.024 | -0.093 | 0.002 | -0.076 | -0.007 | 0.226 | 0.027 | -0.058 | -0.014 | 0.063 |

Note: green and pink colors mark positive and negative significant (at 5% level) coefficients respectively, coefficients in white cells are not significant

People involved in NGOs are more likely to prioritize privatization and less likely - decentralization and procurement reforms. People who participate in protests are more likely to name army and education reform as a priority and less likely - tax and judicial reform (naturally, today protest activity is very limited, and street protests are usually related to reminding the government about Ukrainian prisoners of war).

People who participate in law development are more likely to prioritize digitalization and decentralization (perhaps as enablers of their activity) and less likely - healthcare and education reforms.

Those who donate, were volunteers before the full-scale war or plan to become volunteers are more likely to prioritize army reform, while current volunteers put more emphasis on anticorruption.

People who think that public servants should have higher than minimum salary are more likely to prioritize education and digitalization and less likely - healthcare reform for 2025.

People who participate only in local elections or rarely participate in any elections are less likely to prioritize army reform and anticorruption - perhaps they are less interested in current affairs.

People who are employed or serve in the army are more likely to prioritize tax reform as opposed to those who are out of the labour force, and army servants are more likely to aspire for the army reform in 2025. In contrast, government servants are less likely to prioritize army reform and more likely - healthcare.

Education reform is prioritized by people under 35, those who have children, people with higher education, and women. Women and people under 35 also prioritize healthcare reform (a possible explanation may be that they care more about the health of their older relatives).

There are three reforms which were included into our 2025 priorities list but not into questions on importance of reforms or their social benefits: customs, pension reform, and EU integration. We included all the variables on reform importance and their benefit for society Into the estimation of probability that a person names these reforms as 2025 priority. These cross-reform effects turned out to be insignificant; only people who believe that public service reform is important are more likely to prioritize customs reform for 2025. Employed people and those younger than 35 are less likely to prioritize customs reform, while those who live in the West - more likely.

Pension reform is prioritized by people without higher education, those who are out of the labour force, and those who expect from reforms primarily increase in welfare, longevity, and life satisfaction. Probably these people are worried that their pensions will be insufficient (very often under “reform” people will understand the increase in pensions rather than, for example, changes in the pension system design).

EU integration is more likely to be a reform priority for people 45+, for those who expect that reforms will increase welfare, and for those who think that corruption, lack of political will, and lack of money are the major obstacles to reforms. Probably these people believe that alignment of Ukraine with EU norms will reduce corruption and increase welfare.

Conclusions and policy implications

Ranking of reforms by importance remains practically unchanged since 2022: digitalization, healthcare, army reform, and anticorruption remain the top four. Ukrainians’ view on expected reform results and obstacles to reforms are also very similar to what we observed in 2022. However, the gap between reduction of corruption and all other expected reform results, such as increased welfare or life expectancy, became wider. This suggests that corruption became less socially acceptable. This observation is supported by the fact that today “lack of political will” is the first among obstacles to reforms (up from the second place in 2022). “Passiveness of citizens” is the third most important obstacle to reforms, up from the fifth place in 2022. This suggests that Ukrainians believe that citizens can and should take more responsibility for implementation of reforms.

We also find that civic activity, especially participation in elections, is correlated with higher support for certain reforms. Usually, a person who is likely more familiar with a certain area marks reforms in this area as more important or more beneficial for society. We also find that people who believe that public servants should get higher than minimum salary are more likely to mark many reforms as important and/or beneficial for society. Today, a somewhat lower share of people than in 2022 are ready to cope with material or organizational hardship during the transition period when a reform is deployed.

Therefore, we recommend that:

- the government and media should intensify explanatory communication about reforms. This communication should be both retrospective (for example, how things are different today compared to 5-10 years ago and how this improved our current life) and forward-looking (e.g. what will change for Ukrainians when EU rules are introduced in certain spheres);

- the government should not think in the paradigm of “unpopular reforms”. Reforms are generally quite popular with Ukrainians, and with appropriate communication people will support their implementation. In particular, explanations of how public service works and how the government plans to increase its efficiency, can both attract new people to the sphere and reduce support for populistic moves towards bureaucracy;

- the government (especially local governments) should be more open to citizens’ participation, and civic activists or media should explain how this participation may be organized and which instruments are available for this. Such forms of civic participation as public hearings, discussion of draft laws or civic councils are especially important for the support of Ukrainian democracy today, when elections are impossible.

Annex

Table A1. Regional distribution of respondents before and after February 24th, 2022

| region | before | now | settlement type | before | now |

| Centre | 26.6% | 28.1% | village | 32.1% | 29.5% |

| East | 10.3% | 6.6% | city 0-50k | 21.7% | 20.6% |

| Kyiv | 8.5% | 9.0% | city 50-100k | 5.5% | 5.0% |

| North | 14.3% | 14.5% | city 100-500k | 16.2% | 16.1% |

| South | 13.9% | 10.7% | city 500k+ | 24.5% | 25.0% |

| West | 26.4% | 27.2% |

Regions’ description: East: Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv oblasts, West: Volyn, Zakarpattya, Lviv, Ivano-Frankisvsk, Ternopil, Rivne, Chernivtsi; North: Zhytomyr, Kyivska, Sumy, Chernihiv; South: Zaporizhzhya, Nykolaiv, Odesa, Kherson; Centre: Vinnytsia, Dnipropetrovsk, Kirovohrad, Poltava, Cherkasy, Khmelnytsky.

Table A2. In your opinion, can the following actions of public servants or local officials be classified as corruption?

| yes | this is not corruption | this is not a good deed but not corruption | depends on additional conditions | don’t know | |

| Getting a bribe | +2 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Getting a kickback | +2 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Using an office car for personal purposes | 1 | 0 | +2 | 1 | 0 |

| Visiting an oligarch’s birthday | 1 | 0 | +2 | 1 | 0 |

| Taking a gift from friends that cost over UAH 10 000 | +2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Taking home laptop from work | 0 | +2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Taking office furniture after leaving the job | +2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Joint vacation of a head of another state institution | 0 | 1 | 1 | +2 | 0 |

| Helping friends to pass the competition for public service position | 1 | 1 | 1 | +2 | 0 |

| Signing contract for provision of services with a permanent supplier without competition | 1 | 1 | 1 | +2 | 0 |

| Civil servant's relatives receive a gift from business about which the civil servant has to make decisions (for example, air tickets for relatives of the deputy head of the State Aviation Service of Ukraine) | +2 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Assigning higher bonuses to more loyal employees | 1 | 0 | +2 | 1 | 0 |

| Allocating a space in the yard of a multiflat building for own car | +2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Hiring a relative as a subordinate | +2 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Faster consideration of an issue for a small “tip” (e.g. chocolates) | +2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| A person that has medical education simultaneously works at a hospital and in public service | 1 | 1 | 1 | +2 | 0 |

| A tax inspector starts working at an enterprise which he previously inspected in three months after leaving tax inspection | 1 | 0 | +2 | 1 | 0 |

| An employee of the State Auditing Service checks a government agency where his nephew works | 1 | 0 | +2 | 1 | 0 |

| Hiding information on corruption cases among fellow public servants | +2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Note: “+” indicates the correct answer, a person gets 2 points for this answer. Other numbers in cells indicate the number of points a person gets for those answers. Situations used for the “simple” corruption index are marked with bold.

Figure A1. Histograms of corruption indices

Note: Theoretically, the highest number for the index based on answers to all the questions is 38, for the index based on three questions - 3.

Table A3. Definition of employment (% of total number of respondents)

| employed | ||||

| in private sector | public servant | employee of a state or communal enterprise | ||

| employee | 26.7% | 2.7% | 13.5% | - |

| private entrepreneur | 5.3% | - | - | - |

| working pensioner | 1.3% | 0.2% | 1.5% | - |

| working student | 0.9% | 0.1% | 0.3% | - |

| Military service | - | - | - | 3.2% |

| Works only in the own household | - | - | - | 6.1% |

| Non-working pensioner | - | - | - | 11.1% |

| Non-working student | - | - | - | 3.0% |

| Unemployed, looking for a job | - | - | - | 15.1% |

| Unemployed and not looking for a job* | - | - | - | 3.3% |

*This category is defined as “totally out of labour force” and used as a base in regressions

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations