Ukraine’s defence military complex is undergoing reform. Now is the time to act on lessons learned.

There is a new Ministry in Ukraine and it’s causing a stir.

On 22 July, 2020, the Ministry of Strategic Industry (MSI) was established. As the name suggests, its responsibility is to develop Ukraine’s strategic industries – strategically. The recently appointed Vice-Prime Minister Oleh Uruskyy assured that the MSI will realize the sustainable development of strategic industries, create new jobs, increase state budget revenues, and facilitate regional development.

Stringent civil oversight and control, together with public monitoring and evaluation, are vital to preventing the MSI from becoming a Ministry of Plenty. In Orwell’s 1984 dystopia, “The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism” manifests a Ministry in control of Big Brother’s economy, commanding the plebs to continuously manufacture useless weapons without providing them means of production.

The MSI is a communist construct dating back to Soviet times. Independent Ukraine has already had one – in the form of the Ministry of Industrial Policy (MIP). In December 2010 (the same month the state-owned defence concern UkrOboronProm (UOP) was created under the Kremlin’s overseeing eye), then-President Viktor Yanukovich reorganized the MIP into the State Agency for Management of State Corporate Rights and Property. The very next month, Yanukovich appointed the renegade Minister of Defence Dmitri Salamatin – both now under Russian protection – General Director of UOP. Shortly thereafter, the MIP was reinstated.

In 2014, amid the Euromaidan Revolution and Russia’s violent strategic separatism, Ukraine’s reformers merged the MIP with the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade. Their aim was increasing management efficiency and cutting expenses.

Despite the best reform efforts, the post-Soviet political-criminal nexus remains active in Ukraine today. This fact was recently and pointedly depicted by the publicized assertions made after President Zelensky’s meeting with the Head of British Intelligence MI6, Richard Moore. Nobody knows how many billions have been mismanaged and embezzled from state institutions, but Ukraine’s current economic, financial and defence situation attests their related histories. In recent years, Ukraine’s state-owned defence military complex has seen a fair share of public corruption scandals. Some of them even led to accusations of complacency from within the National Anti-corruption Bureau. Heaven forbid the same old corruption is permitted to infiltrate the new Ministry.

The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine (CMU) Decree No. 819 (7 September 2020) codifies the Ministry as “the main body in the system of central executive bodies, which ensures the formation and implementation of state industrial policy, state military-industrial policy, state policy in the sphere of state defence procurement, in the sphere of defence-industrial complex, in the aircraft industry and ensures the formation and implementation of state policy in the field of space activities.” Other strategically important state-owned enterprises (SOEs) may also fall under the Ministry’s responsibilities. Despite appearances to the contrary, Uruskiyy asserts the MSI does not plan on controlling the economic activity of enterprises; rather, it will develop and implement state industrial policies.

Over 103 overarching stipulated tasks – both broad and specific – have been delegated to the MSI. As it stands, the Ministry may be in a position to simultaneously strategize, appoint, govern, participate, monitor and evaluate itself. Numerous abuse of power risks and factors of nonalignment with best international practice, particularly the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, have already been identified. In 2014, the OECD launched a vital, country-specific project supporting Ukraine’s anti-corruption agenda for improved relations with the EU, NATO, and IMF, among others.

Alarmingly, a recent Constitutional Court ruling declared anti-corruption provisions related to government officials and unlawful enrichment unconstitutional. By proxy, jeopardizing the integrity of future MSI appointees. Currently, only seven individuals are working in the yet to be budgeted Ministry.

The MSI will take control over Ukraine’s defence industry: the state defence order (SDO), governance and management. Its purported plan also includes taking UOP and creating a future Defence Systems of Ukraine (consisting of nine defence holding companies), and an Aerospace Systems of Ukraine (consisting of six holding companies).

In line with Soviet tradition, the MSI is also known as MinStratehProm. Without effective civil oversight and control, it risks becoming a hybrid vertical institution not only analogous to, but worse than, UkrOboronProm. Its mission reflects UOPs official purpose codified in 2010 by CMU Decree № 1221, namely, “…increasing the efficiency of state-owned enterprises engaged in economic activities in the field of development, manufacture, sale, repair, modernization and disposal of weapons, military and special equipment and ammunition and participate in military-technical cooperation with foreign countries…”.

Notably, key experts assert UOP was purposefully designed as a structure for graft with the eventual aim of integrating Ukraine’s defence complex with Russia’s (Rostec). In less than a decade, UOP did very little to innovate, increase capabilities, capacities or increase exports. Today, of the 137 defence companies under its umbrella, 10 account for 90% of the profit, 21 have been pilfered by Russian forces and 15 are bankrupt. Less than a half of the remainder have been deemed viable for salvage and development by the state; they stand to be moved to the auspices of the MSI.

UOP’s Transformation Strategy: The roadmap to modernization and corporate governance

Few would disagree that UOP needs to be dismantled, Ukraine’s Military Complex corporatized, its unneeded assets privatized and the rest be made attractive for investment and international partnerships. It is now time for UOP’s metamorphosis and the reconstruction of Ukraine’s public and private defence and dual-use industries.

The reform-minded leadership within UOP has developed a strategy in which it becomes the corporate center of transformation. With over 14 proposed key roles including corporate governance reform, automatization of processes and digital systems, and improving SDO procurement, the +/- 3 year transition timeline is tight. According to the First Deputy Director Roman Bondar, UOP aims at “improving product quality, attracting engineering talent and raising social standards; seeking investments and setting up joint ventures; developing new technologies and new, competitive, product platforms to stimulate exports.”

Ukraine, a Wassenaar Arrangement participant, ranks 14th in global arms exports. Its position has been dropping steadily since 2013. This decline is partly related to the 2014 partial de facto deferral of defence and dual use exports resulting from Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine’s territorial sovereignty. During this “threatening or special period”, the Ministry of Defence must permit the export thereof in addition to the State Service of Export Control. In principle, the logic limiting exports to secure the needs of the national armed forces appears sound. Practice, however, reflects the idiom, “If I can’t have it no one can.” Despite not being procured through the SDO, many available domestic technologies are blocked for export. With much of what Ukraine could be exporting going nowhere, the deferral appears ripe for review.

UOP indicates an export value of over $500M. Ukrspecexport’s Director Vadim Nozdria recently announced the state-owned import/export intermediary is engaged in 200 contracts valued at over $1.5B. Experts representing Ukraine’s private defence manufacturers assert the current foreign trade activity is unsatisfactory, and exports could easily increase by $500-700M per annum. These figures could reach over $2B within a few years pending legislation and UOP’s transformation, according to the Head of the Association of Ukrainian Defence Manufacturers (AUDM) Ruslan Dzhalilov.

Few realize that well over 200 private Ukrainian companies are associated with defence manufacturing organizations like the AUDM and League of Defence Companies of Ukraine. AUDM represents over 100 companies employing about 3000 people.

Once globally recognized as a security and defence leader of the Soviet Union, Ukraine is capable of effectively reclaiming – and surpassing – its former status, but pervasive corruption and nonsensical, unautomated bureaucracy hinder advancement. The Head of the Executive Committee of Ukraine’s National Reform Council, Micheil Saakashvili emphasizes, “Ukraine’s defence industry is full of great potential, but time is extremely short! Ukraine must save and develop its defence industry. And… if you ask where you should get the money for all of this? Sell! [what is produced Ed.].”

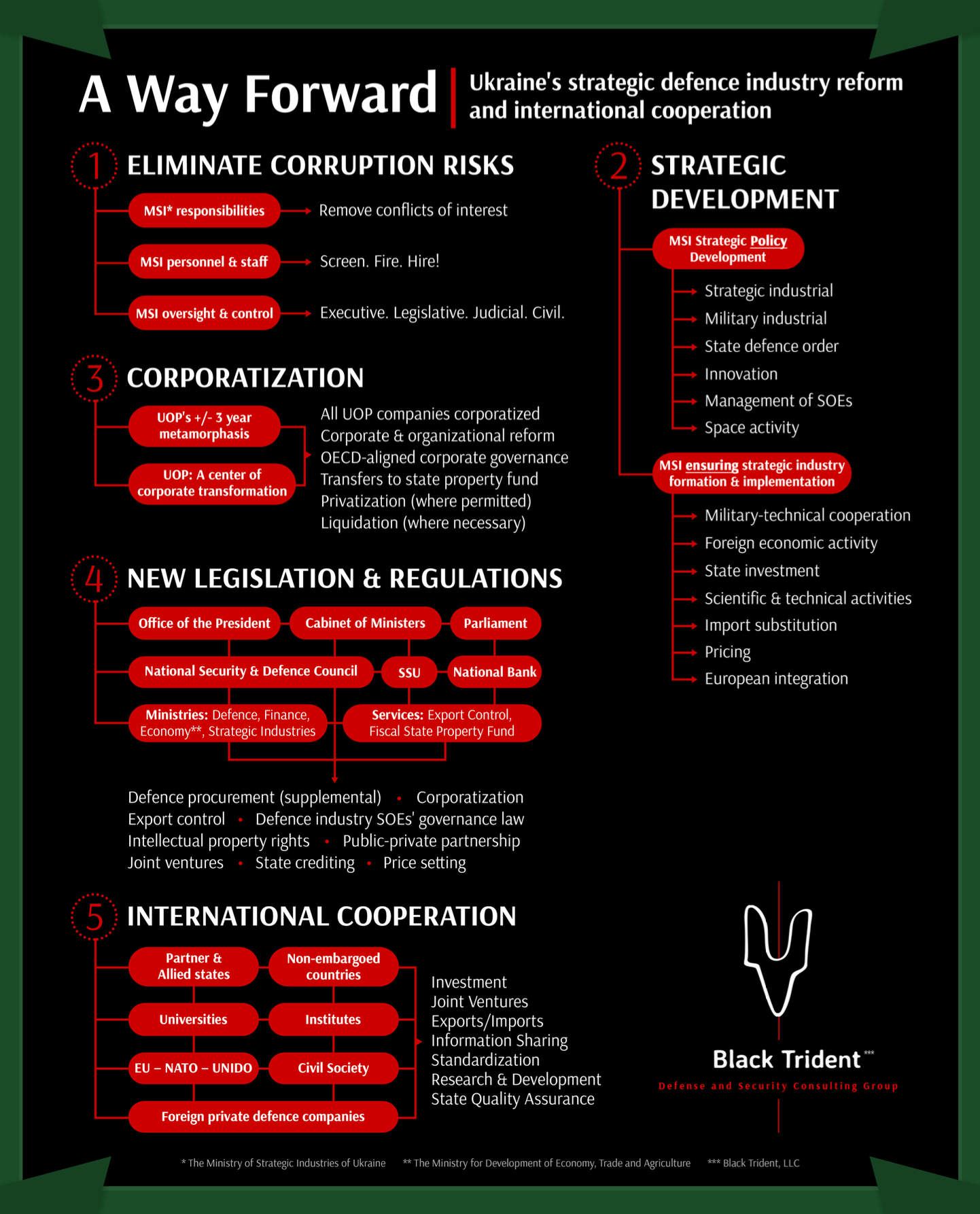

The Way Forward: Reform & International Cooperation

Draft Law No. 3822 on the Reform of Ukraine’s State-owed Defence Industry covers transformation matters. Its provisions must be designed to serve the national interest, particularly as provided by Ukraine’s 2020 National Security Strategy. It must be worked on and scrutinized by experts with integrity, and then passed by Parliament. Many other issues must be addressed, from profit-limiting Soviet-style pricing formulas to sanctions against the Russian Federation. They include:

- Eliminating corruption risks associated with the abuse of power in the structure of the new MSI by fixing those mandated powers which contradict the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance,

- Appointing individuals to the MSI who have passed thorough evaluation and selection procedures and are clear of all conflicts of interest and criminal histories.

- Allowing the reformers within UOP to implement the corporate transformation as proposed, while the MSI develops effective strategic policies.

- Guaranteeing transparent and effective parliamentary oversight and control supported by public monitoring and evaluation by civil society.

- Assuring governance reform adheres to international best practices.

- Simplifying, digitizing, and automating SDO procurement and export control procedures

- Reviewing the 2014 deferral of defence exports with the aim of only limiting the exports of those goods to be procured by the state.

- Drafting and implementing new legislation and regulations, including:

-

- Defence Procurement supplemental documents improving transparency and budgeting timelines;

- Joint Venture and Intellectual Property Rights aligned with EU principles;

- Export Control with increased transparency, simplified processes and prompt turnaround;

- Public-Private Partnership and cooperation; and

- Private defence and dual-use market advancement.

Notably, some progress has been achieved with the private defence sector. In April, President Volodymyr Zelensky rescinded UOP’s rights to influence marketing, market access, and pricing in export contracts. Much work lays before the public and private sectors.

Innovation, production and the sharing of defence/dual-use technology are more critical now than ever. The repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Nations’ global ceasefire, and the “new normal” all indicate previously defence-oriented technology will become instruments of Agenda 2030 sustainable development goals.

That is why, in Ukraine, the MIS and UOP need to act in the national interest cooperatively ensuring the institutional integrity of corporatization (as developed by UOPs reformers) and the implementation of future, progressive and viable, strategies as developed by the MIS. Only then will their commitments to international cooperation with corporations and organizations including the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, NATO and the EU have meaning. Ukraine and its strategic partners need to think, learn from their pasts, cooperate, build and not sell out.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations