As the full-scale war in Ukraine enters its fourth year, new nationally representative data reveal a silent mental health crisis hiding beneath the surface of resilience.

A September 2025 KIIS survey of 2,000 Ukrainians shows that while 23.2% meet clinical thresholds for anxiety and 19.8% for depression, only 6.3% describe their mental health as “bad” or “very bad.” Despite widespread symptoms, 89.0% sought no professional help in the past year, citing cost (43.9%), limited availability (25.0%), and stigma (17.2%) as key barriers—while one in four relied on sedatives or sleeping pills. AI chatbots such as ChatGPT or Gemini reach only a tiny fraction of those in need: just 9.0% say they would be “very likely” to use such tools, and 42.0% “very unlikely.” The findings reveal that Ukraine’s mental health challenge is not only one of need but of recognition, access, and trust, raising urgent questions about how to build affordable, stigma-free, and scalable support systems with AI chatbots offering one potential solution.

The Mental Health Picture

As the large-scale war approaches its fourth year, evidence suggests that it has taken a toll not only on the economy but also on people’s minds. With traditional psychological services scarce and expensive, could artificial intelligence offer a scalable solution, or do Ukrainians remain too skeptical to embrace it?

We commissioned a series of questions in the September 2025 Omnibus survey conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), relying on a nationally representative sample of 2,000 Ukrainians, to examine mental health status and help-seeking behavior nearly four years into the full-scale invasion.

Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), a validated four-item screening tool comprising two anxiety items (GAD-2: feeling nervous/anxious and inability to control worrying) and two depression items (PHQ-2: loss of interest and feeling down/hopeless) (Kroenke et al., 2009), we find that 23.2% of respondents met the clinical threshold for probable anxiety, 19.8% for depression, and 17.7% for combined psychological distress. Yet, when asked to rate their mental health directly, only 6.3% described it as “bad” or “very bad.” These numbers are somewhat below the estimates we obtained in May 2025, perhaps, reflecting a highly dynamic nature of mental health in a war setting.

What is interesting, the concordance between self-rated health and three measures based on PHQ-4 is rather weak. By concordance we mean that respondents would have “yes” or “no” for both measures but not a mix of “yes” for, say, anxiety, and “no” for bad or very bad self-rated health. In our sample only 79,5%, 83,2%, 84,8% of responses for anxiety, depression and distress coincide with self-rated health (either good or bad).

To contextualize these figures, pre-pandemic benchmarks using the same PHQ-4 scales found anxiety rates of 8-10% and depression rates of 7-10% in the U.S. and Germany (CDC 2019; Hajek & König, 2020). During COVID-19, rates across seven European countries (including Germany, UK, France, and Italy) peaked at 41% for depression and 33% for anxiety in late 2020, declining to 29% and 28% respectively by April 2021 (Hajek et al., 2022). Therefore, Ukraine’s 2025 rates fall between typical Western baselines and pandemic-era peaks.

The 17-percentage-point gap between standardized screening and self-assessment warrants attention. This discrepancy may reflect normalization of wartime stress, differences between clinical and everyday understandings of mental health, or reluctance to report psychological difficulties. Regardless of the root cause, a substantial portion of the population experiences symptoms that reveal the scale of Ukraine’s mental health challenge, which affects nearly one in four Ukrainians.

Access Barriers and Current Help-Seeking

Despite the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms, 89.0% of respondents had not sought mental health help in the previous 12 months. Overall, in the sample only 3.9% saw a psychologist, 3.9% consulted a psychiatrist, 2.8% used AI chatbots (ChatGPT, Gemini), 1.1% tried but failed to obtain help, and 0.7% mentioned other sources (mostly family or other doctors).

When asked about barriers to accessing mental health services, respondents identified the following major constraints (multiple options possible for one respondent):

- Cost: 43.9% cited financial constraints

- Availability/logistics: 25.0% mentioned limited services or transportation difficulties

- Privacy concerns: 19.7% worried about confidentiality

- Stigma: 17.2% feared judgment

- Uncertainty: 27.2% selected “hard to answer”, an unusually high proportion for this response category, possibly indicating discomfort with the topic

These findings indicate that access barriers operate on multiple levels: economic, infrastructural, and social.

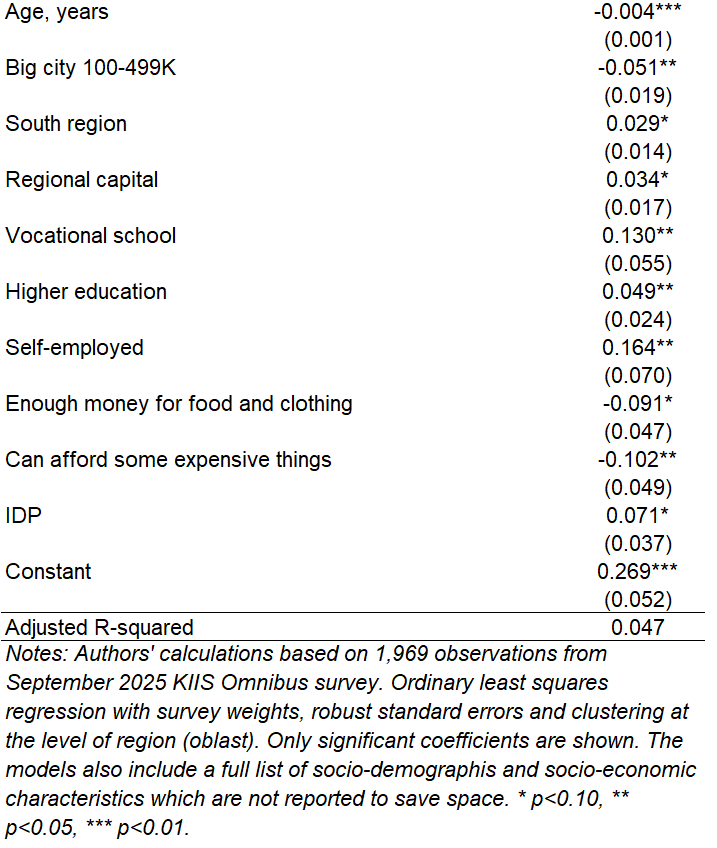

Regression analysis of help-seeking behavior reveals that self-employed, higher and vocational education individuals are more likely to seek mental health help (Appendix Table A1). On the other hand, older respondents coming from big cities and with more extra income show lower rates of help-seeking. These patterns may reflect differential exposure to stressors, varying access to services, or differences in mental health literacy across groups.

Medication Use

Regarding sedatives and sleep aids, 25.5% of respondents reported using them in the previous month, elevated compared to North American and European benchmarks for benzodiazepine prevalence ranging from 4% to 8% (Ma et al. 2023), though direct comparison is complicated by differences in measurement periods and the Ukrainian survey’s inclusion of plant-based remedies alongside pharmaceutical benzodiazepines. The survey did not distinguish between prescribed medications and self-medication, nor between benzodiazepines and milder herbal remedies like valerian. However, the disparity between sedative use (25.5%) and professional mental health service access (7.8%) raises questions about whether medication may be substituting for unavailable professional care. Given established risks of long-term usage, especially when it comes to benzodiazepine, monitoring these patterns warrants policy attention.

Exploratory regression analysis reveals demographic correlates of sedative use. Unemployment shows the strongest association, with unemployed respondents substantially more likely to report use. Internally displaced persons, retirees, women, and older respondents also show higher likelihood of usage. These patterns are correlational and do not establish causal relationships, but they may help identify populations warranting closer attention in monitoring efforts.

Attitudes Toward AI-Based Mental-Health Support

Recent technological developments have introduced digital and AI-driven mental-health tools as potential complements to traditional services. While medication use can lead to potential long-term problems of substance abuse, AI tools may provide a low-cost and convenient alternative that is anonymous and free from stigma.

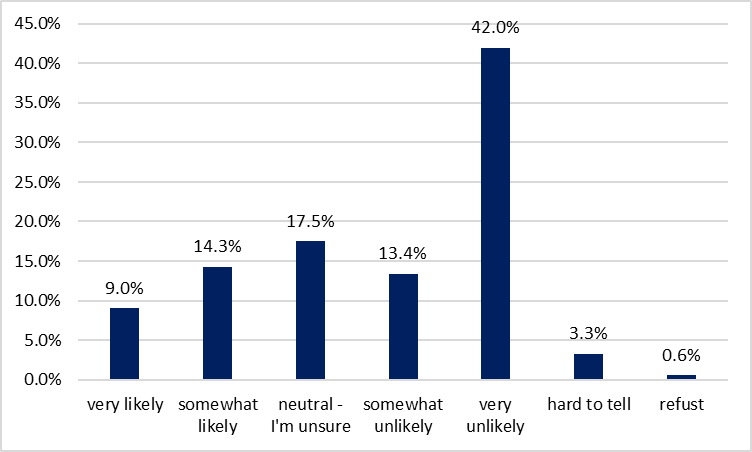

Figure 1. How likely is it that you would use an AI chatbot for mental health support if you needed help?

Note: Authors’ calculations based on KIIS Omnibus survey for September 2025. One option only.

The KIIS data provide one of the first systematic assessments of Ukrainians’ attitudes toward such technologies. The results show a cautious and often skeptical public. When asked about their likelihood of using AI chatbots for mental health support if needed, 42.0% said they would be “very unlikely” to do so, with another 13.4% “somewhat unlikely,” totaling 55.4% expressing clear resistance (Figure 1). Only 9.0% said they would be “very likely” and 14.3% “somewhat likely” to use such tools, a combined openness rate of 23.3%. The remaining 17.5% were neutral or unsure.

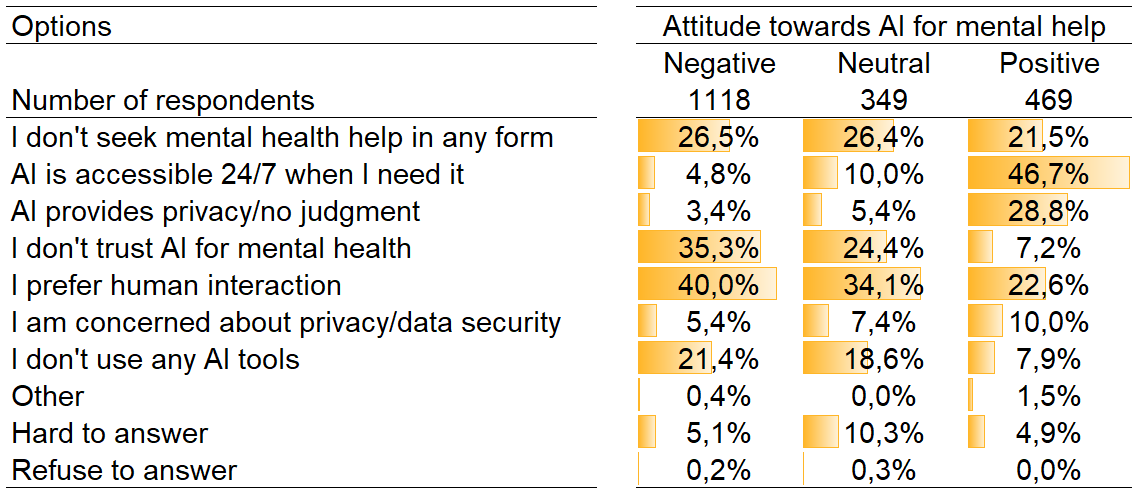

To analyze respondents’ views on AI mental health we grouped them into 3 groups based on their attitude to mental health AI chatbot. We combined answers “somewhat unlikely” or “very unlikely” into a group of 1,118 respondents with “Negative” attitude, 349 respondents chose option “Neutral” because they were unsure and 469 respondents had “Positive” attitude combining the groups who were “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to use AI chatbot if the need arises. Table 1 shows the distribution of views on AI use for mental health by those three groups.

Table 1. Views on AI mental health shown by attitude towards AI chatbot use

Note: Authors’ calculations based on KIIS Omnibus survey for September 2025. Multiple options possible.

Across all groups, the share of respondents not seeking mental health help at all remained relatively consistent (21.5–26.5%), highlighting that openness to AI tools largely reflects perceptions of technology itself rather than overall help-seeking behavior. Respondents with negative attitudes most frequently cited a preference for human interaction (40.0%) and distrust of AI for mental health (35.3%), showing clear skepticism toward technological solutions. Those with neutral attitudes shared similar concerns but at lower rates, 24.4% and 34.1% correspondingly. At the same time, these issues were less important for respondents with positive attitudes – only 7.2% expressed preference for human interaction and 22.6% didn’t trust AI for mental health. By contrast, respondents with positive attitudes emphasized AI’s practical advantages: nearly half (46.7%) valued its 24/7 availability and 28.8% its privacy and lack of judgment.

Survey answers reveal that the majority prioritizes human connection and expresses skepticism about algorithmic approaches to mental health. A smaller segment (23%) appreciates the practical advantages of digital tools: constant availability and reduced social friction. For this receptive minority, AI chatbots might provide an alternative to self-medication or no support at all, particularly in rural or conflict-affected areas where professional services are unavailable. However, the substantial resistance rate, driven primarily by the value placed on human empathy and doubts about AI’s suitability for mental health, indicates that digital tools should be positioned as supplements to, rather than replacements for, traditional care to reach a wider audience.

Demographic patterns reveal limited variation in AI openness. Residents of smaller and mid-sized cities express lower likelihood of using AI mental health tools compared to those in larger urban areas, possibly reflecting differences in technology familiarity or internet infrastructure.

Discussion

The September 2025 KIIS survey reveals a substantial gap between measured psychological distress and help-seeking behavior in Ukraine. While 23% screen positive for anxiety and 20% for depression using standardized instruments, only 6.3% self-assess their mental health as poor, and 89% have not sought any form of mental health support in the past year. This pattern, widespread symptoms, limited recognition, minimal help-seeking, operates against a backdrop of significant barriers: 44% cite cost as prohibitive, 25% face availability or logistics challenges, and stigma concerns persist.

Sedative and sleep aid use adds another dimension: 25.5% of Ukrainians reported use in the past month, somewhat higher than typical European rates. The disparity between this figure and professional mental health engagement (7.8%) suggests medication may substitute for unavailable psychological care rather than complement integrated treatment.

Against this backdrop, AI-based mental health tools present an ambiguous prospect. Only 23% of respondents expressed openness to using AI chatbots for mental health support, with 55% explicitly resistant and the remainder uncertain. The most common objections centered on preference for human interaction (32%) and distrust of AI for mental health purposes (26%), while a minority appreciated 24/7 accessibility (15%) and anonymity (9%). These attitudes suggest that while digital tools promise to deliver services to hard to reach populations, they face substantial adoption barriers which warrant further investigation.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

In sum, the data reveal a paradox in Ukraine’s mental-health landscape. While self-reported well-being suggests resilience, standardized screening tools indicate widespread levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. These findings highlight both urgent policy needs and critical knowledge gaps about how to build safe and effective mental health support structures during and after prolonged conflict.

The central challenge is one of scale: the war’s mental health impacts will persist long after active combat ends, creating sustained demand that Ukraine’s existing mental health workforce cannot meet. Addressing this demand-supply gap requires not only expanding traditional services but also investigating how emerging technologies, particularly AI-driven tools, can responsibly augment capacity.

Several immediate priorities emerge from the data. Service expansion through multiple channels is needed to address the cost and accessibility barriers cited by the majority of respondents. Primary care integration offers particular promise: embedding mental health screening and brief interventions in routine medical visits leverages existing infrastructure and reduces stigma associated with specialized mental health services. Community mental health teams, whether mobile or community-based, can reach populations in areas with limited providers, particularly in conflict-affected and rural regions. Given the shortage of licensed mental health professionals, training community health workers or peers in evidence-based brief interventions can expand capacity more rapidly than traditional professional training pipelines.

Systematic monitoring of medication use is also warranted given the elevated rate of sedative use (25.5%). Such monitoring should ensure that pharmacological treatment remains appropriate and supervised rather than substituting for unavailable psychological care. This includes establishing prescription monitoring databases to identify patterns of long-term use or potential over-prescription, and developing clinical guidelines for appropriate benzodiazepine use in conflict settings.

The 17-percentage-point gap between objective screening and self-assessment raises important questions about recognition and help-seeking that require further investigation. Rather than assuming awareness campaigns will close this gap, research is needed to understand why Ukrainians experiencing clinically significant symptoms do not recognize them as such, whether this reflects adaptive coping, stigma, or limited mental health literacy, and which interventions, if any, can effectively shift recognition and subsequent help-seeking behavior in the short term.

Finally, the potential role of AI-driven mental health tools deserves systematic investigation. While only 23% of Ukrainians currently express openness to AI mental health support, these tools could provide scalable, low-cost options for populations where traditional services are unavailable. Concerns about safety are legitimate, given documented cases of general-purpose chatbots failing to appropriately advise users in crisis. However, purpose-built applications such as Wysa and Youper take a different approach, delivering evidence-based cognitive behavioral therapy with additional integrated safety protocols. Early trials suggest they can significantly reduce depression and anxiety symptoms, though primarily for mild-to-moderate cases (Fitzpatrick et al., 2017).

Substantial knowledge gaps remain. What forms of AI support are effective for war-affected populations? What are the risks of deployment in contexts with ongoing cyber threats? How can these tools be designed and governed as complements to, rather than substitutes for, professional care? Addressing these questions requires rigorous testing before widespread deployment.

The data suggest not a single intervention but an integrated system where professional services, appropriate medication oversight, and emerging technologies complement one another. Building such a system will require sustained investment alongside systematic research to ensure that expanded services are not only scalable but safe and effective for those suffering amid ongoing uncertainty.

References

- Fitzpatrick, K. K., Darcy, A., & Vierhile, M. (2017). Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (Woebot): a randomized controlled trial. JMIR mental health, 4(2), e7785.

- Hajek, A., Sabat, I., Neumann-Böhme, S., Schreyögg, J., Barros, P. P., Stargardt, T., & König, H. H. (2022). Prevalence and determinants of probable depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in seven countries: Longitudinal evidence from the European COvid Survey (ECOS). Journal of affective disorders, 299, 517-524.

- Hajek, A., & König, H. H. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of individuals screening positive for depression and anxiety on the phq-4 in the German general population: findings from the nationally representative German socio-economic panel (GSOEP). International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(21), 7865.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B. and Löwe, B., 2009. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), pp.613-621.

- Landolt, S., Rosemann, T., Blozik, E., Brüngger, B., & Huber, C. A. (2021). Benzodiazepine and Z-drug use in Switzerland: prevalence, prescription patterns and association with adverse healthcare outcomes. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 1021-1034.

- Ma, T.T., Wang, Z., Qin, X., Ju, C., Lau, W.C., Man, K.K., Castle, D., Chung Chang, W., Chan, A.Y., Cheung, E.C. and Chui, C.S.L., 2023. Global trends in the consumption of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in 67 countries and regions from 2008 to 2018: a sales data analysis. Sleep, 46(10), p.zsad124.

Table A1. Results from linear probability model for respondents who sought or received mental help

Disclaimer

This research was financed by The Medical Faculty at the University of Oslo for the implementation of the project: “The Repercussions of War Violence in Ukraine: Consequences for Mental Health, Substance Abuse and Utilization of Primary Health Care”. The funder didn’t have involvement in the research design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in the writing of the report. All views are of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funder.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations