In emerging markets, “fear of floating” often exists—a desire to keep the exchange rate (almost) stable at any cost. Ukraine abandoned its fixed exchange rate regime in 2015, reintroduced it at the start of the full-scale war to suppress panic, and, as of October 3, 2023, switched to a managed floating regime. This article examines what prevails in this regime—”management” or “floating.”

The concept of fear of floating was introduced in 2000 by Carmen Reinhart and Guillermo Calvo to describe a situation where countries limit exchange rate fluctuations despite publicly declaring a floating FX regime.

This characteristic feature is driven by the exceptionally high dependence of macro-financial stability on a stable exchange rate.

Therefore, central banks in these countries try to smooth exchange rate fluctuations through foreign exchange interventions. Their reaction function (the implicit rule for setting the key interest rate) includes a parameter that implies a strong response to exchange rate movements. The toolkit of interventions and monetary policy decisions also includes capital controls.

Reasons behind the fear of floating

The fear of floating is primarily driven by structural factors, including:

- Extremely high sensitivity of inflation to exchange rate fluctuations (strong pass-through effects);

- Lack of trust in the central bank and macroeconomic policy in general;

- Dependence on imports (energy or high-tech), which prevents currency depreciation from providing a stimulating effect on exports;

- A significant role of external borrowing in financing budget deficits and corporate investment due to an underdeveloped domestic financial market. As a result, the exchange rate does not fulfill its traditional stabilizing role due to balance sheet effects—the cost of servicing external debt rises with depreciation;

- Dollarization, which fuels additional demand for foreign currency during both significant depreciation and appreciation of the national currency. Depreciation threatens financial stability by raising the cost of servicing foreign debt. At the same time, appreciation faces resistance from those holding foreign currency assets as the local currency value of those assets declines (recall the backlash over the hryvnia’s appreciation in 2019);

- Export pricing in foreign currency, which makes current account adjustment occur more through a reduction in imports rather than an increase in exports due to depreciation.

Most of the more advanced emerging market economies have to a large extent overcome the fear of floating. This was achieved through multiple rounds of structural reforms aimed at

- limiting inflation by implementing inflation targeting;

- strengthening central bank independence to address trust issues;

- developing the domestic financial market in the national currency;

- building institutional capacity for countercyclical fiscal stabilization;

- strengthening the rule of law as a key prerequisite for deepening the banking system and capital markets;

- creating a favorable environment for foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows.

Why this issue matters for Ukraine

Before the major financial sector reforms that began in 2015, Ukraine fully matched the textbook definition of a country with a fear of floating. However, significant changes followed, including the adoption of inflation targeting, the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves, and the radical recovery of the banking sector. Fiscal policy reforms were equally striking: the budget deficit became more countercyclical, the hryvnia-denominated domestic government bond market deepened, and long-term instruments emerged.

With the onset of full-scale aggression, the situation changed completely: on February 24, 2022, the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) switched to a fixed exchange rate and introduced capital controls. The return to a floating exchange rate regime in 2023 and the gradual shift back to inflation targeting in 2024 are taking place in a highly unfavorable structural environment and under a completely different risk profile. The budget deficit has reached 20% of GDP, the trade deficit remains significant, external financing plays a crucial role in funding current expenditures, and the depth of the foreign exchange market has not even come close to its 2015 level. The population still prefers saving in foreign currency due to fears of devaluation. Given these circumstances, the restoration of exchange rate flexibility in 2023 is unlikely to resemble the introduction of exchange rate flexibility in 2015. On the other hand, the main challenge posed by the fear of floating is that it significantly limits monetary policy flexibility and its ability to correct macro-financial imbalances.

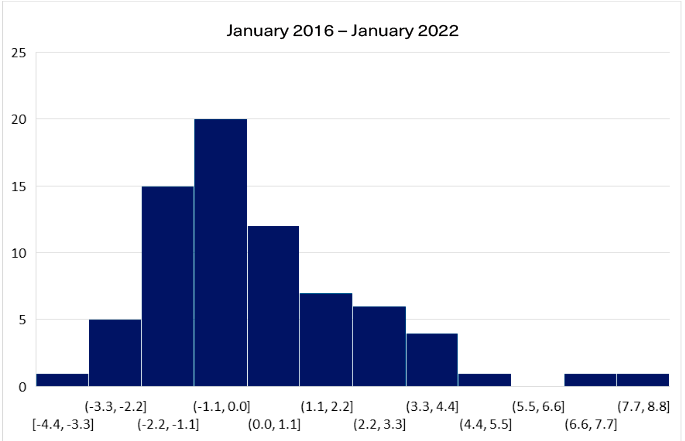

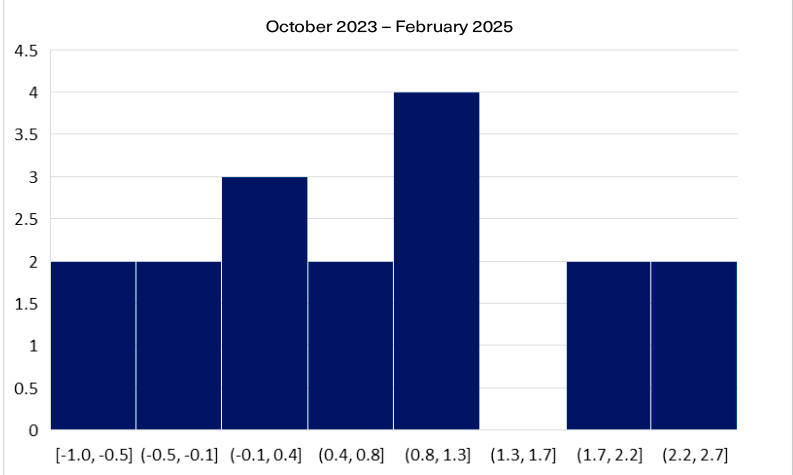

Since the flexibility of the hryvnia exchange rate has been significantly lower during the war than before 2022, there is a risk that the fear of floating could become a structural feature of the domestic economy. Figures 1–3 illustrate substantial differences in the nature of UAH/USD volatility before the full-scale invasion and after the restoration of exchange rate flexibility. (Figures 1–3 present monthly data, while the difference is even more pronounced in the daily data—see Annex).

Figure 1. Distribution of exchange rate changes (% month-over-month), 2016–2022

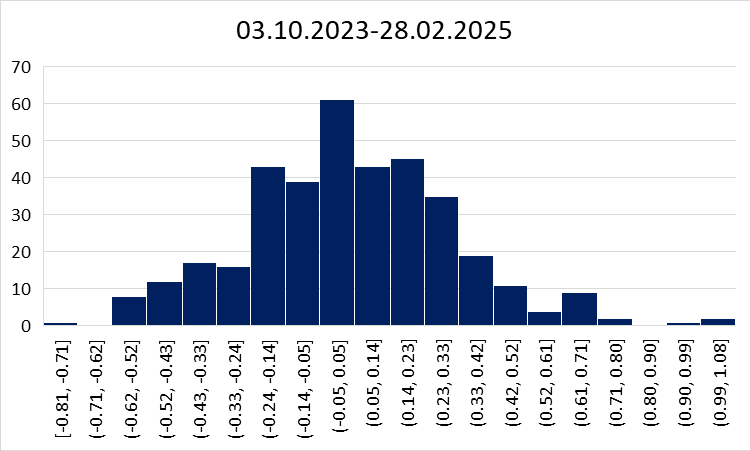

Figure 2. Distribution of exchange rate changes (% month-over-month), 2023–2025

Source: NBU data, author’s calculations. Note: Positive values indicate depreciation, while negative values indicate currency appreciation.

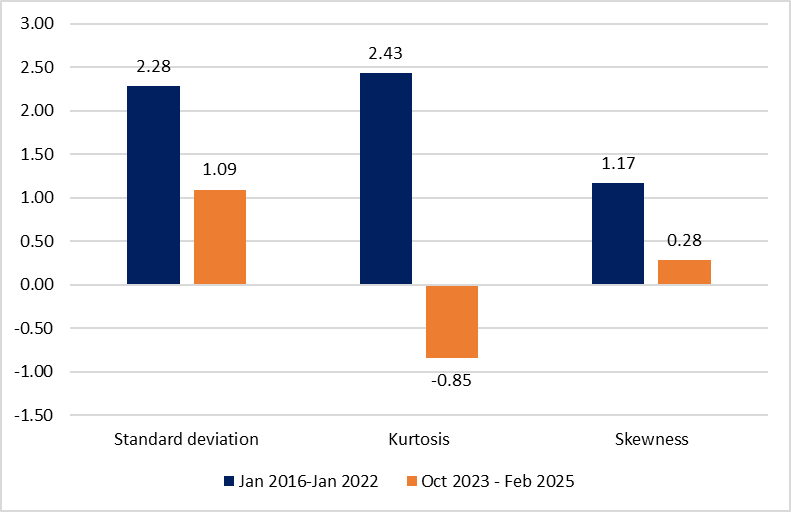

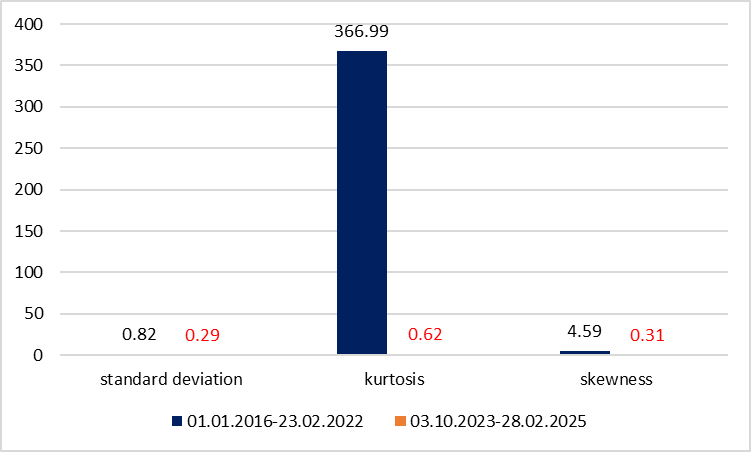

Figure 3. Standard deviation and other moments of exchange rate change distributions

Source: NBU data, author’s calculations.

Figure 3 shows that the intensity of exchange rate fluctuations (measured by standard deviation) was more than twice as high between January 2016 and January 2022 compared to the period from October 2023 to February 2025. In other words, the range of exchange rate changes was significantly broader in the pre-war period than after the return to flexibility.

An even more pronounced shift occurred in the kurtosis indicator, which reflects how concentrated (high kurtosis) or flat (low kurtosis) a distribution is. In this case, it indicates the degree of similarity in exchange rate fluctuations (Figure 3). Before the full-scale war, exchange rate changes occurred within a broader range but were mostly small and clustered near the center of the distribution. Since late 2023, the range of fluctuations has narrowed, but exchange rate movements now more frequently reach the limits of that range. The kurtosis value also sheds light on how exchange rate fluctuations are smoothed. A higher kurtosis suggests a greater likelihood of extreme exchange rate movements and less smoothing. Conversely, a low or negative kurtosis indicates that smoothing is substantial, preventing extreme fluctuations. This outcome is expected, given the differences in the functioning of the foreign exchange market and the design of currency interventions.

The symmetry of exchange rate movements has also changed, as reflected in the skewness indicator (Figure 3). A significantly positive skewness in the first period indicates a greater tolerance for depreciation pressure, which allowed for a more flexible monetary policy. In contrast, the low skewness value in the second period suggests that the NBU is actively trying to avoid significant depreciation. In both periods, the hryvnia depreciated more frequently than it appreciated. However, in the second period, the depreciation has been more controlled, reflecting the unique conditions of the current environment.

Although signs of fear of floating restrict the flexibility of wartime monetary policy, the chosen strategy has a rational foundation.

First, under the influence of strong non-economic shocks, the exchange rate retains its role as a nominal anchor of stability. Ideally, this role should be phased out, but for now, expectations regarding exchange rate movements significantly affect the behavior of economic agents. The choice of savings currency and the banking system’s stability will remain interconnected for a long time.

Second, the nature of the trade deficit and the structure of imports and exports clearly rule out a scenario where setting the exchange rate based on supply and demand balance would restore equilibrium. Export prices are determined in foreign currency, while imports include a significant energy component, as well as critical goods for defense capability, whose substantial price increase due to an illusory correction of the trade deficit does not seem justified given the current level of foreign exchange reserves.

Third, exchange rate pass-through effects are nonlinear. The stronger the non-economic risks and the more news fuels concerns about the future, the more exchange rate fluctuations translate into price changes. On the other hand, maintaining high real interest rates to curb currency demand is undesirable due to the need to restore lending. Weakening the pass-through effects is possible when economic agents perceive exchange rate fluctuations in both directions as normal and inflation declines. Reducing inflationary pressure through a significant currency appreciation is unlikely due to the structure of foreign trade. However, at the end of 2023 and the beginning of 2024, when inflation was below target, the NBU allowed greater depreciation.

Remedies for the fear of floating

The experience of emerging market economies, including Ukraine, shows that overcoming the fear of floating is possible. However, doing so during wartime and amid new structural challenges is extremely difficult. Two policy options can be considered.

Option one involves maintaining the status quo. Since the structural challenges stem from the war, addressing the fear of floating should align with the broader trend of improving security conditions. In other words, the NBU should not significantly alter its intervention policy but rather strike a balance between the pace of bringing inflation to target, preserving foreign exchange reserves, and gradually correcting external imbalances. The primary risk of this approach is the entrenchment of expectations for minimal exchange rate fluctuations and reliance on a narrow range of currency flexibility. As a result, macro-financial stability would become increasingly dependent on maintaining high real interest rates.

Option two involves expanding the range of exchange rate fluctuations while initially retaining positive real interest rates. The advantage of this approach is that the economy would gradually adapt to larger exchange rate swings, allowing monetary policy to become more flexible. However, this strategy carries several risks. It works best when exchange rate fluctuations can move in both directions and currency appreciation is not perceived as artificial. Of course, with ample foreign exchange reserves, interventions could be structured to ensure flexibility in both directions. But to what extent would this approach align with the goals of correcting external imbalances and maintaining a steady accumulation of foreign exchange reserves?

Regardless of the circumstances, the war remains the key factor constraining exchange rate flexibility. However, this does not mean the risks of entrenching the fear of floating should be overlooked.

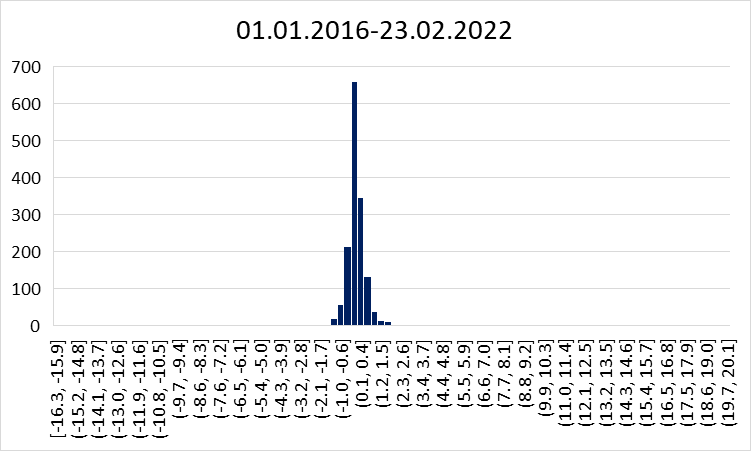

Annex.

Figure A1. Daily change in the UAH/USD exchange rate, %, 2016–2022

Figure A2. Daily change in the UAH/USD exchange rate, %, 2023–2025

Source: NBU data. Note: Negative values indicate hryvnia appreciation, while positive values indicate depreciation.

Figure 4. Standard deviation and other distribution moments

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua/

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations