The war of attrition has led to an unprecedented increase in defense expenditures in Ukraine’s budget. However, even with Western assistance, these funds are still insufficient to match the level of Russian military spending. Therefore, to further enhance support for the Defense Forces, it is essential to evaluate Ukraine’s financial capacity taking into account the experience of other countries in the 20th century.

On October 31, 2024, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, professor at the University of California, Berkeley, a researcher of monetary and fiscal policies, and a member of the editorial board of Vox Ukraine, delivered an online lecture on Ukraine’s financial resilience during wartime. This text summarizes the key ideas of the lecture.

The topic of Ukrainian finances during the war is very broad. Therefore, Yuriy Gorodnichenko focused his lecture on how Ukraine can finance a war of attrition, the resources available, potential sources of additional funding, and the role of the financial system under current conditions.

The disparity in military expenditures: a key challenge in a war of attrition

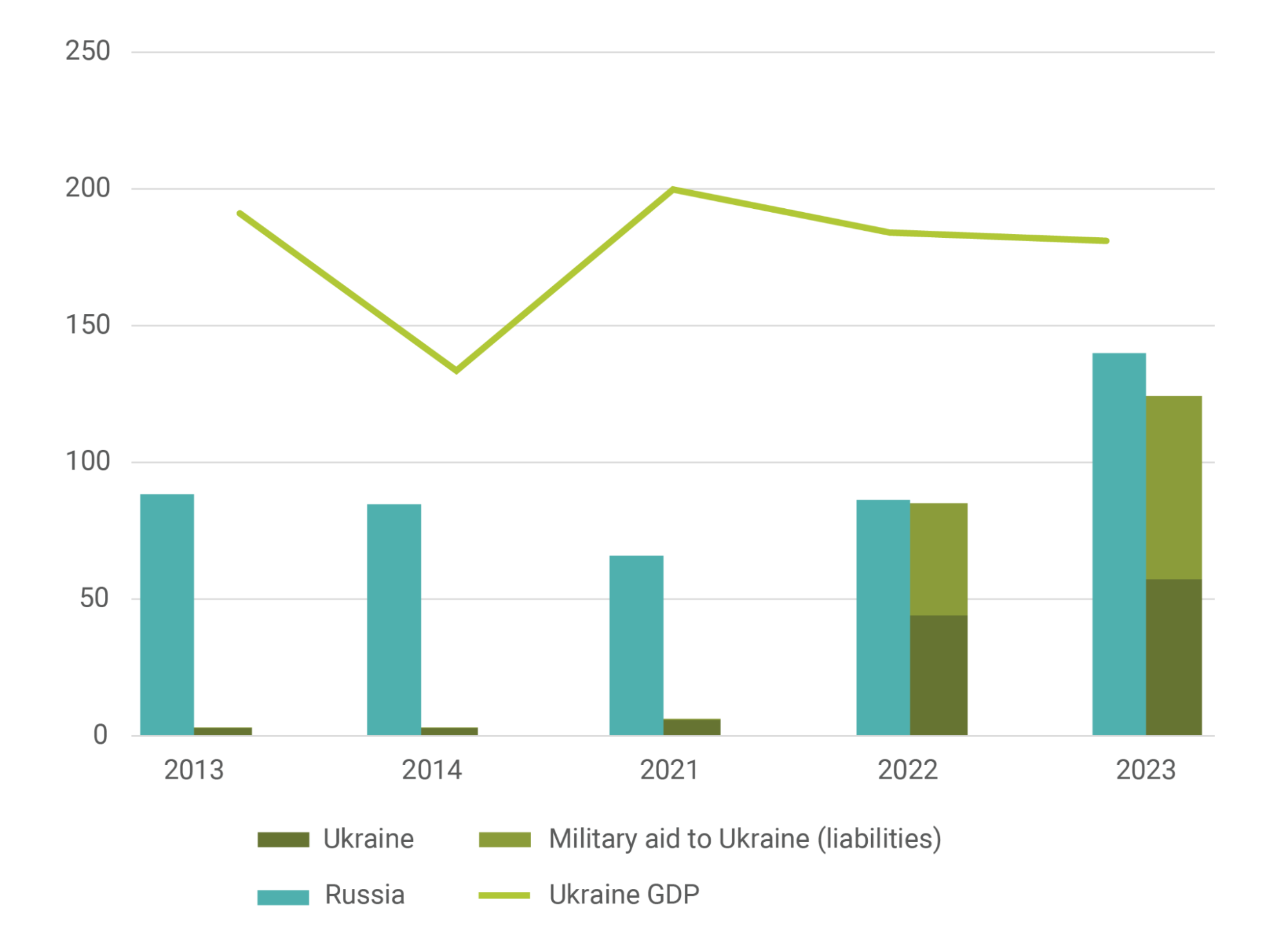

The primary issue of finance and war has remained unchanged for over a decade: Ukraine’s defense expenditures have consistently been no match to those of Russia. In 2013, Ukraine spent 30 times less on its military than Russia. Following the onset of the war in Donbas and the annexation of Crimea, this gap gradually narrowed, yet funding still remained significantly lower.

Even from February 24, 2022 to the present, parity has not been achieved, with the gap between Ukrainian and Russian defense expenditures reaching $100 billion in 2023 and 2024 (Table 1). The challenge persists in the 2025 budget, as we cannot avoid 1) military expenditures, 2) spending on social protection, and 3) the costs of servicing the national debt.

Figure 1. Comparison of defense expenditures of Ukraine and Russia

Fortunately, allies’ support has helped and will help narrow this gap in the coming year. However, even the combined sum of Ukraine’s own resources and international assistance falls $20-30 billion short of Russia’s military expenditures.

Domestic political challenges in Western countries mean that closing this gap will always be uncertain and difficult. This became obvious from delays in U.S. aid this year.

Thus, in order not to fall behind the enemy, the state must maximize the mobilization of funds that contribute to Ukraine’s GDP.

World War II as an example of successfully mobilizing domestic financial resources

The experience of World War II shows that allocating substantial funds relative to the size of a nation’s GDP is an achievable task. In desperate times, Germany and Japan spent over 70% of their GDP on the war. The United Kingdom and the United States were not far behind, maintaining expenditures at around half of their gross domestic product. How exactly did these countries manage to achieve this?

Figure 2. Military expenditures of the allies and the Axis powers (1939-1944), % of GDP

Recognizing their vulnerable positions and the need to make swift decisions, Western economists at the onset of the war considered different ways to mobilize colossal amounts of defense funding. Naturally, they were also concerned about the potential macroeconomic consequences of various approaches.

The two most effective options are a combination of government bonds and increased taxes. Other measures, such as monetary emissions, are less effective: these short-term solutions create critical imbalances in the country's economy, which will inevitably backfire sooner or later.

Option 1: Government bonds

In his 1940 essay "How to Pay for the War," British economist John M. Keynes argued that the best solution for financing the war was to strongly encourage households, especially high-income ones, to save and invest in government bonds.

From Keynes's perspective, the advantage of this strategy lies in the ability to spread the burden of repaying the bonds with interest over 20–40 years. This provides citizens with an option for long-term investment guaranteed by the state while the government receives much-needed funds immediately. However, Keynes believed that borrowing alone would not be sufficient for Britain to finance the war. Therefore, the most optimal strategy was a combination of war bonds and taxes.

It is unclear whether Franklin D. Roosevelt read this essay, but during World War II, the United States adopted a similar structure for financing the war. Approximately 40% of military expenditures were covered by taxes, while the remainder came from borrowing and monetary issuance.

Historical note

Series E Bonds were U.S. Treasury bonds issued from 1941 to 1945. The first bond was purchased by President Roosevelt himself to promote this form of investment. Overall, the government successfully leveraged this instrument: through seven War Loan Drives, 85 million Americans purchased bonds totaling $185.7 billion. Borrowing funds from citizens helped the U.S. finance over a quarter of its wartime expenditures (The Economics of World War II, p. 108).

This is quite typical in the history of war financing by the United States. With the exception of the Korean War, most wars were primarily financed by borrowing (Chart 3):

Figure 3. War financing by the United States

Option 2: Taxes

If government bonds fail to raise sufficient funds, the next best option is to increase taxes. However, several conditions must be observed: luxury consumption should be taxed, tax rates should be progressive, and any increase should be gradual and non-aggressive. Otherwise, the policy risks demotivating citizens from working and saving.

Thus, theory highlights the significant role of borrowing in maintaining stable war financing. The key question then is: how much funding can Ukraine’s financial system allocate for defense needs through debt instruments?

To answer this question, let’s examine the key indicators of the financial system's capacity:

- Stock market conditions

- Private debt market

- Deposits

- Health of the banking system

- Access to external markets

- Savings

- Assets (buildings, ports, roads, etc.)

- Reserves

Let’s start with what is currently inaccessible to Ukraine.

Gaps in Ukraine's financial market

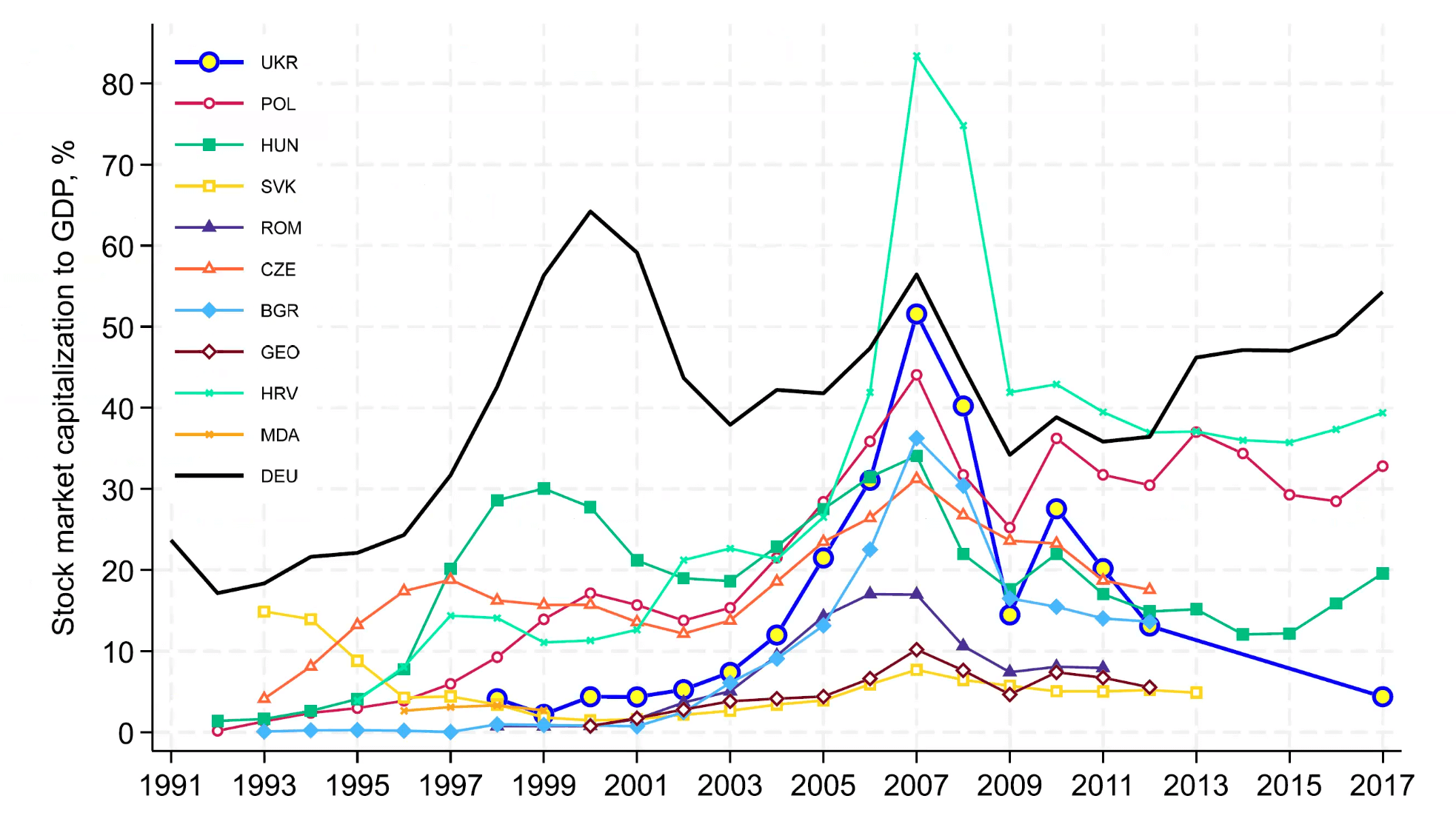

Stock market and private debt market

Effectively, Ukraine does not have a stock market—its current capitalization relative to GDP is close to 0%.

Figure 4. Stock market capitalization to GDP (%)

Source: World Bank data

We witnessed a peak in market capitalization in 2007. However, during the 2008 recession it became clear that this growth was a bubble. Consequently, there are no financial flows to redirect towards defense.

The situation with institutional investors such as pension funds and the mortgage market is similar. In pre-war times, their share relative to GDP did not exceed 2-3%—a far cry from the target of covering a 20-30% GDP deficit, as noted earlier.

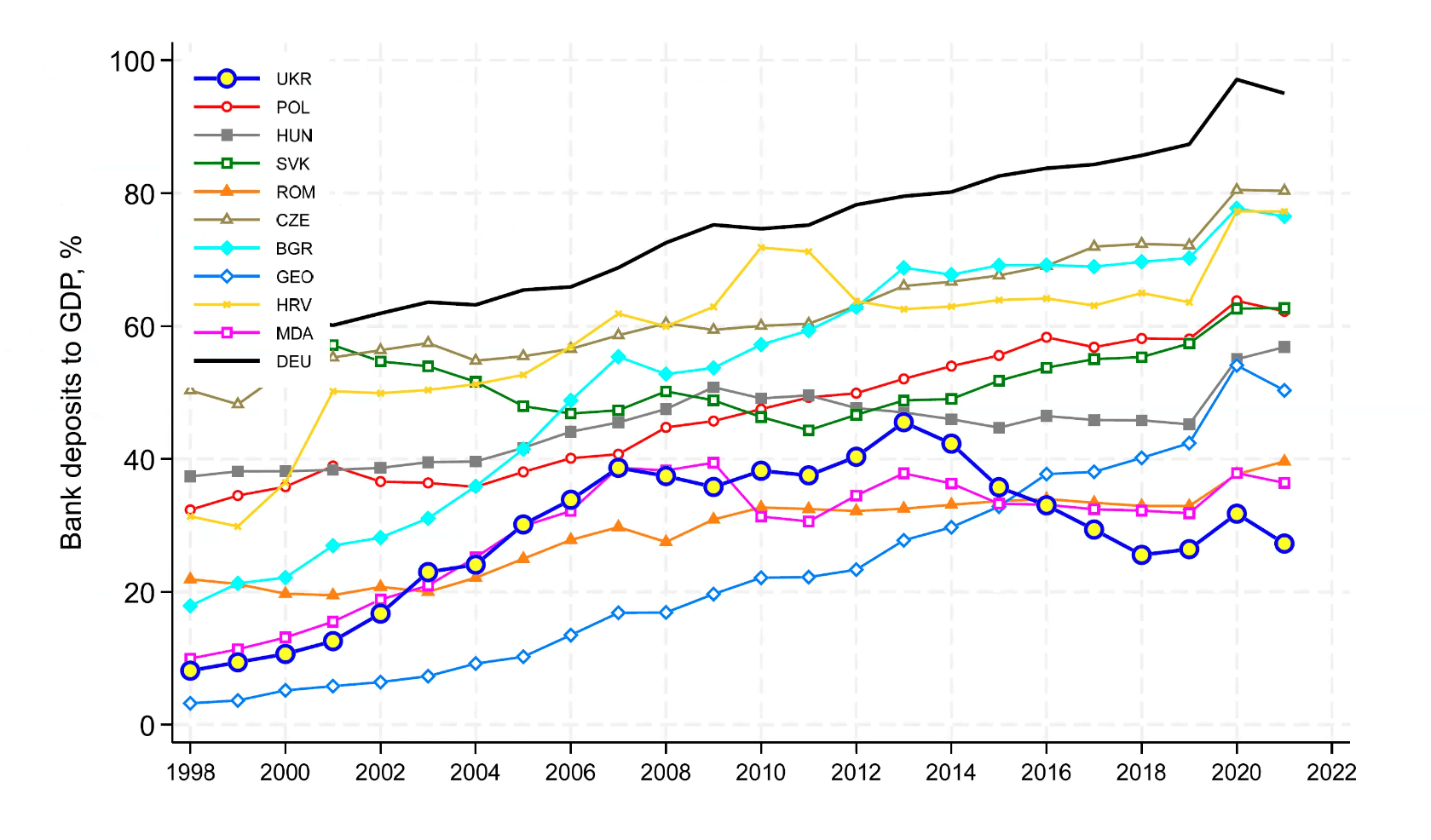

Deposits and the health of the banking system

The volume of deposits in the domestic economy is relatively high —their pre-war level was around 25% of GDP.

Figure 5. Bank deposits to GDP (%)

Source: World Bank data

This is a significant resource that could potentially be mobilized and redirected to the state—e.g., by increasing investments in war bonds using these deposits.

However, two key problems arise. The first is that, given the current budget deficit, this resource may last for only a year or two, making it far from a long-term solution.

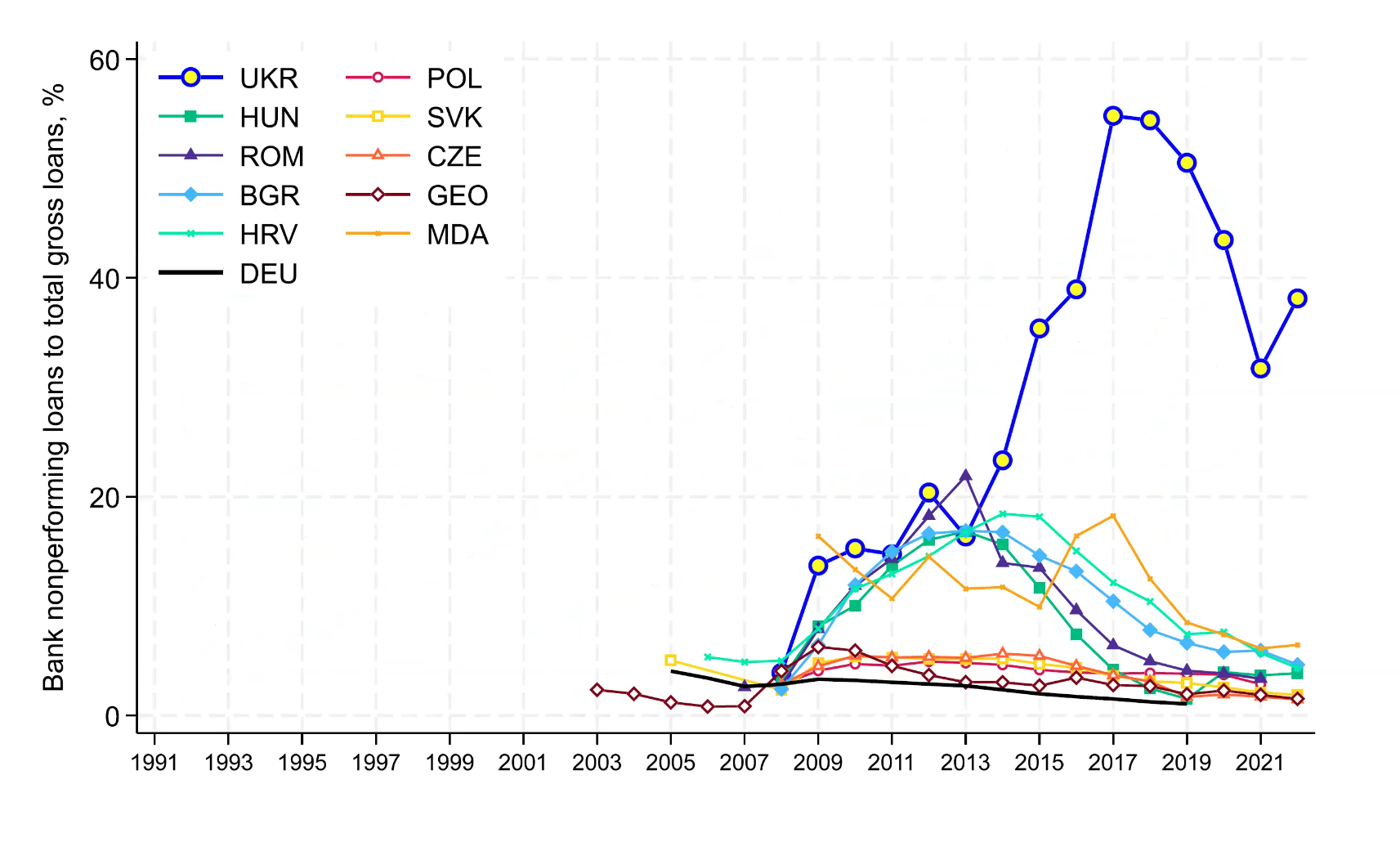

The second issue is the poor health of the national banking system. Since the Great Recession of 2008-2009 and the events of 2014, Ukraine has experienced a significant increase in non-performing loans (around 50% - ed.), which limits the banks' ability to finance any projects.

Figure 6. Banks’ non-performing loans to total gross loans

Source: World Bank data

Access to External Markets

Under normal circumstances, access to external markets enables private businesses to attract more funds from abroad, generating a certain return: each invested hryvnia could potentially yield an additional 1, 2, or 3 hryvnias—the so-called "multiplier effect." Ultimately, this can increase both state revenues and the funds available for investment in war bonds.

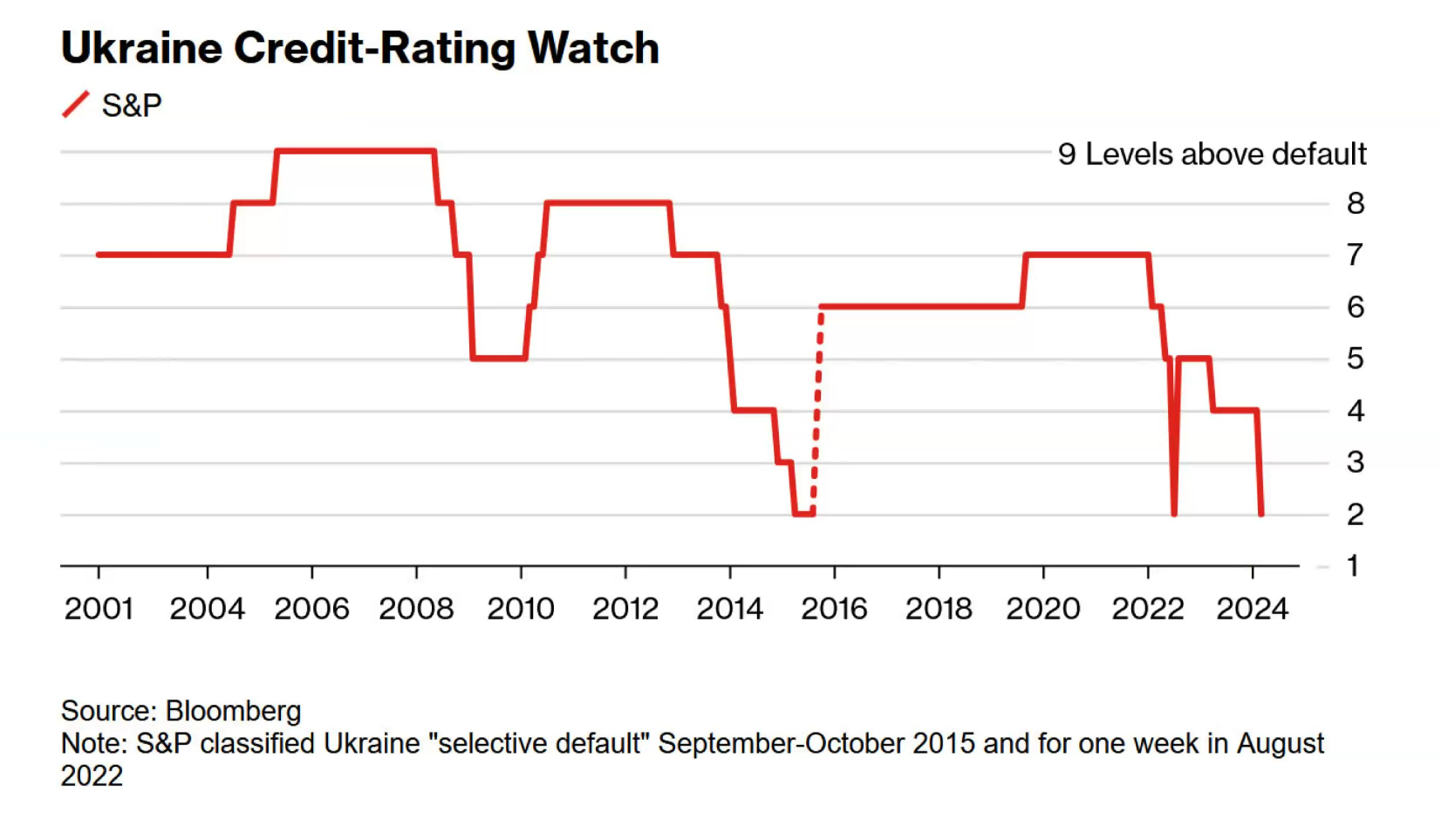

However, Ukraine is currently in a state of de facto default: although the government has not formally declared it, the state is unable to service its existing debts. This is a significant blow to the country's credit rating (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Ukraine's credit rating (2001–2024)

The country's low credit rating breeds distrust among foreign investors, effectively cutting Ukrainian private businesses off external financial markets. As a result, loans to the private sector cannot serve as a viable source for financing the war.

The options outlined above reveal the gaps in Ukraine's financial system's capacity to finance the budget deficit and support the Defense Forces. So, what tools are promising?

Potential sources of deficit financing

Savings

Of course, not all money in the country is held in bank deposits. Some is kept "under mattresses" by citizens, either in foreign currency or hryvnia. It is difficult to estimate the exact amount, as updated government data indicates that the shadow economy grew to 40% in 2023 due to several factors, including those related to the war.

According to official statistics, as of October 2024, citizens had accumulated UAH 1,325.7 billion. However, the total volume of savings could be higher, and this should be taken into account.

Assets

This essentially involves the privatization of buildings, ports, roads, minerals, land, and other assets owned by the state.

In 2023, $4 billion was raised this way, half of which came from privatizing the Hotel "Ukraine." Considering the scale of the deficit, this might not seem like a particularly promising avenue. However, compared to most countries worldwide, Ukraine has a substantial portfolio of state-owned enterprises. At the central government level, there were 3,293 such enterprises in 2021, with a total equity value of $32.8 billion.

Of course, this resource is best viewed in the context of raising funds for reconstruction, as privatization is a time-consuming process. Moreover, an assessment is needed to determine how much of the nation's wealth will remain intact after the end of hostilities.

Reserves

The National Bank of Ukraine currently holds approximately $39 billion in reserves. This is roughly equivalent to the annual assistance provided by Western partners—enough to sustain the country for about a year if Western support were suddenly cut off.

Potential methods for resource mobilization

So, what can we actually do with the resources we have? Let’s turn to historical experience: what share of government debt is held by different financial market participants, and how have we previously mobilized resources through the financial system?

Currently, our domestic debt stands at UAH 1.6 trillion, with the largest creditors being banks and the National Bank of Ukraine, holding 46% and 42% of the debt respectively. Is this the limit of the banks' capacity to finance the Defense Forces?

In fact, there is still room for action. As shown in Table 3, net claims on central government bodies amount to UAH 856 billion—these are investments in domestic government bonds (OVDPs) that we discussed earlier.

Table 1. Consolidated balance sheet of banks in Ukraine, excluding the NBU

Source: NBU data

The table highlights two additional potential sources of war financing. The first is claims on the National Bank of Ukraine totaling UAH 773 billion. These are primarily deposit certificates—short-term interest-bearing "deposits" that banks place with the NBU. In this way, the NBU "extracts" excess liquidity from the banking system, helping to curb inflation.

If the state finds a way to redirect these assets, for instance, into war bonds, these funds could be used to finance the Defense Forces.

The second potential resource is over UAH 1 trillion in loans currently fueling the economy. However, redirecting these funds to the military should be done with caution, as the civilian sector also requires substantial credit to maintain economic activity.

Thus, while the banking system has some potential, it cannot fully cover the budget deficit in the long term.

Table 2. Domestic debt by holder categories

Source: NBU data

Finally, in the context of domestic debt financing (Table 4), we have not mentioned non-residents (1%), territorial communities (0%), and, most importantly, legal entities and individuals (2% and 8% of the debt, respectively). These agents contribute minimally to financing our military expenditures through domestic debt purchases. Therefore, the state should focus on increasing their participation in financing of the budget deficit.

Options for moving forward: How can we secure more funds?

Taking into account our financial strengths and weaknesses, untapped potential resources, and possible scenarios for continuing the war, the following combination of measures could help sustain the pace of its financing:

Seigniorage (money printing): This mechanism should be avoided, as it could lead to significant inflation. Ukraine has already had a negative experience with this: in 2022, money printing caused inflation to rise to 25%.

Control over interest rates: This would help maintain stability in the financial market and ensure access to credit.

Democratization of government bond purchases (e.g., "eBond"): A notable example is the U.S. practice during 1941–1945, when the state raised $186 billion through retail bonds, with contributions from 86 million Americans. While the scale in Ukraine is different, even if every second Ukrainian invested in bonds, this could provide a significant resource for partially covering the deficit.

Increasing taxes: This includes raising indirect taxes (such as VAT), focusing on implementing a progressive tax system (e.g., during World War II, the top income tax rate in the U.S. reached 90%), and introducing luxury taxes. Of course, these measures must be accompanied by improvements in the efficiency of tax administration and budget spending.

Maintaining funding for the Defense Forces in such a prolonged war of attrition is indeed a complex task. The solution requires regulatory creativity and the use of all available levers to prevent economic overheating and high inflation while also balancing the fiscal position.

Authors: Authors: Yuriy Gorodnichenko (speaker), Maksym Yovenko (text compilation), Oleksandra Oliinyk (lecture transcript, first draft)

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations