VoxUkraine has extensively discussed this reform, its rationale, and expected results.

To briefly summarize this discussion, decentralization:

- redistributes resources to the local level, provides local self-government with more fiscal and political autonomy and provides it with opportunities to make policy decisions based on the local context;

- improves the quality of public services since people and especially businesses can “vote with their feet” (i.e. register and pay taxes in a community that provides better public services). In general, if a community head has to win popular votes rather than favours from the central government, citizens can expect more attention to their needs;

- is crucial for democracy in two aspects: First, citizens gain leverage over local authorities, as local politicians must win their support. Second, decentralization eventually develops a pool of “grassroots” politicians — those who were successful at the local level and could be elected to a higher office. This decreases the likelihood of inexperienced politicians “parachuting” to important positions;

- lowers the chance of establishing an authoritarian rule: decreasing the powers of a central office makes it less attractive, especially for those who would like to abuse power. Moreover, local governments can counterbalance the central government if it acts in an authoritarian manner. At the same time, the central government should ensure that local governments adhere to the law. It can do this more effectively when it is not directly responsible for the appointment and actions of local authorities.

These are theoretical considerations and practice may differ: for example, in some communities local governments may collude with the largest employers in order to force people to reelect them. Next, we examine how decentralization was implemented in Ukraine and how it was perceived by citizens.

Figure 2.1. Decentralization reforms in 2015-2024, Reform Index data

Note: cumulative score is the sum of event scores. Event scores are derived from surveys of the Reform Index experts

A summary of developments in 2014-2019

Decentralization began in March 2014; it was the first major reform launched after the Revolution of Dignity. Decentralization is a domestic development introduced after about 10 years of policy planning. Decentralization has been highly popular (Figure 2.2), even though many citizens did not experience its effects immediately (Figure 2.3). Moreover, popular support for decentralization reform is persistent: for example, in November 2022, 76% of respondents believed that decentralization reform should continue, while the majority thought that decentralization increased Ukraine’s resilience.

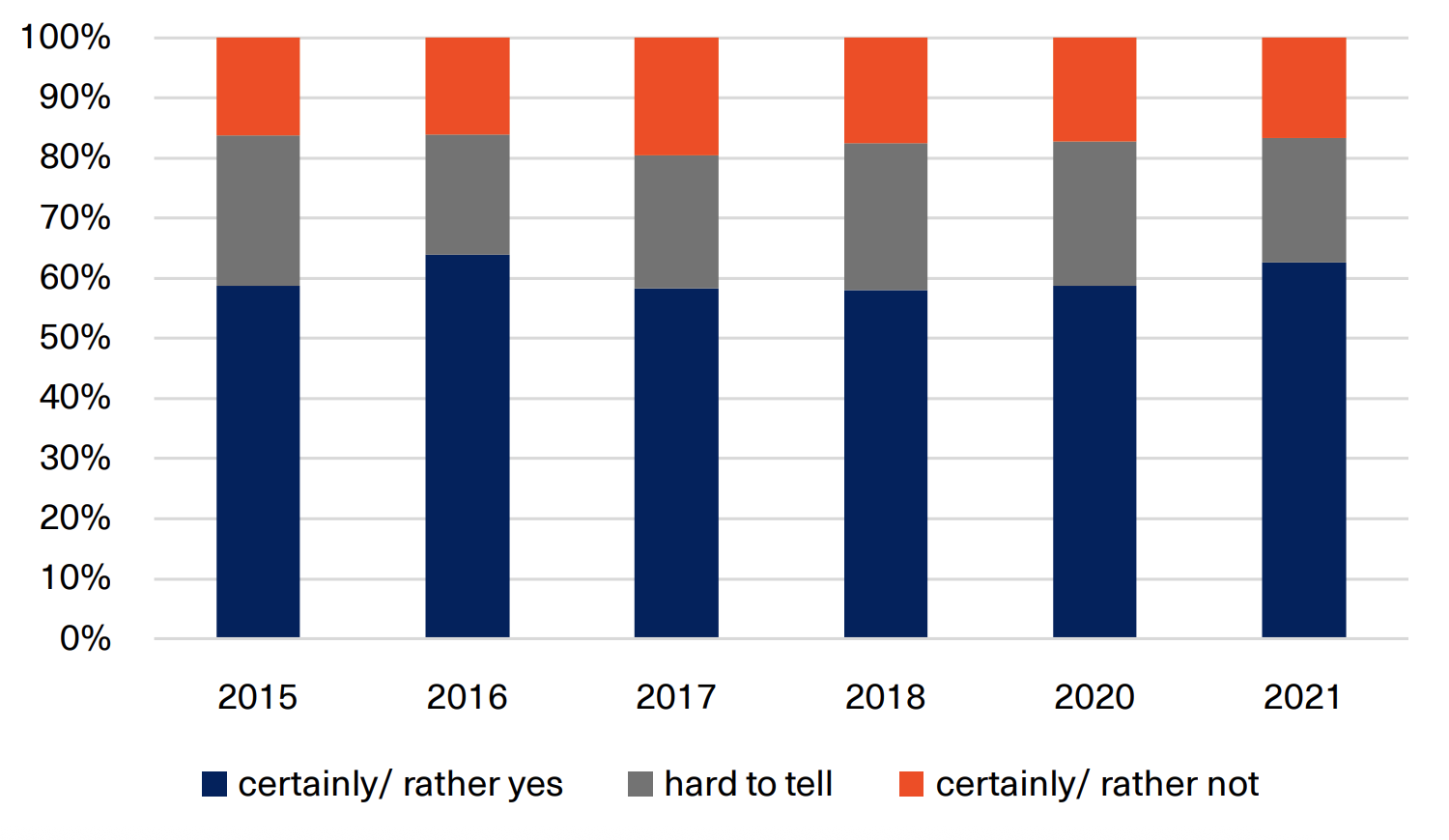

Figure 2.2. Do you think decentralization reform that provides more powers and resources to local governments is necessary or not?

Source: KIIS survey

Figure 2.3. Since decentralization began, local budget revenues have considerably increased. Have you observed any results of using these funds (better quality of services, amenities, social support) compared to previous years?

Source: Razumkov Center survey

Ukrainians were somewhat skeptical about the ability of local authorities to cope with the additional powers and responsibilities provided to them by the decentralization reform (Figure 2.4). Nevertheless, since 2022 we have observed how local authorities (with a few exceptions) were on the frontlines of resistance to the Russian invasion, providing services to citizens and monetary and material support to those who joined the army. One expected result of decentralization reform was increased resilience, largely due to greater cooperation between local government and civil society, activists, and volunteers. Unfortunately, this positive trend has partially reversed since 2023.

Figure 2.4. In your opinion, would your local government be able to handle additional powers and responsibilities obtained in the course of decentralization?

Source: Razumkov Center survey

Decentralization provided communities (especially cities) with the resources to tangibly improve people’s lives. The share of public revenues allocated to local governments did not change much (Figure 2.5), but local authorities received a lot more freedom in the allocation of these resources. Moreover, they received their own major revenue sources (60% of personal income tax and 10% of profit tax), which the central government cannot easily withhold. This allowed local governments to prioritize the needs of their communities. Many communities renovated or provided new equipment to their schools, which they had been unable to do for years. Quite a few communities renovated parks or other public spaces, improved their infrastructure, etc. These public improvements highlight the shift in incentives for local governments.

Figure 2.5. Distribution of revenues between central and local budgets

Source: State Treasury reports, openbudget.gov.ua

The main milestones of the decentralization reform in 2014-2019 were the following:

- the law on decentralization (March 2014) stated general principles of the decentralization reform: the formation of amalgamated communities (hromadas or municipalities), their relation to the central budget, their revenue sources and powers, etc.;

- Budget Code amendments related to decentralization (January 2015): the introduction of healthcare and educational subventions (the methodology for calculation of these subventions was adjusted several times to address inefficiencies revealed during its practical application);

- the law on the formation of hromadas and respective methodology of hromadas formation was adopted in 2015 (the methodology was adjusted several times, and in 2017 was adopted into law);

- the law on local elections (2019) established that local village councils are elected via single-mandate districts, while the councils of cities, rayons (districts), and oblasts (regions) are elected using party lists;

- delegation of powers from the Ministry of Justice to local authorities to register enterprises and entrepreneurs and to provide administrative services (see Reform Index releases 25 and 26). Later, the network of Centers for Administrative Services Provision was established throughout Ukraine so that people could obtain administrative services faster and more conveniently;

- the adoption of several legislative acts providing more powers to local governments in the construction sphere (to approve medium-sized construction projects, register real estate, etc.);

- local governments were allowed to co-finance the construction of roads, salaries for local government employees such as teachers and doctors, stipends for foster families, etc.;

- the transfer of agricultural land from central to local governments, which began in 2018. This change allowed local governments to obtain more revenues from property taxes. However, local governments remain reluctant (or have limited administrative capacity) to introduce and properly administer these taxes (e.g. in 2021, real estate and land taxes constituted only 2% and 4% of local government tax revenues respectively);

- there was also one anti-reform: in 2017, the heads of local administrations were excluded from the list of public servants. This exclusion granted the central government more control over the officials of local administrations and allowed it to appoint them without competitions, at the discretion of the president or the Cabinet of Ministers. In 2019, the new law on public service (see Chapter 1) made local administration officials public servants again.

Reform of healthcare and education financing was a key component of decentralization. Instead of allocating budget funds directly to each of the thousands of hospitals and schools, since 2015 the government has provided medical and educational subventions to hromadas (communities or municipalities) based on the number of patients or students they serve. Communities then decide how to allocate these funds. For example, several communities may jointly finance a district-level hospital that provides service to their citizens. Since 2017 healthcare facilities are paid according to services which they provide (see Chapter 14).

Local governments were not always happy with increased responsibilities because sometimes they had to make difficult decisions. For example, the decision to close a village school is unpopular with locals, even though transferring children to a larger school is beneficial for their education. Nevertheless, local governments made these decisions in consultation with their communities (e.g. a community could decide to continue financing a school from the local budget, even if it was small and inefficient. To “sweeten the pill” of school closures, local governments were allowed to rent out the premises of empty schools since 2021). Local policy discussions allow people to see the connection between the taxes they pay and services they receive, and learn to understand the consequences of their decisions.

As with many other reforms, the implementation of decentralization in Ukraine followed a “deploy — test — adjust” cycle, as legislative gaps and flaws were revealed through practical experience. Consequently, rules and laws related to amalgamation of communities, distribution of subsidies, and other issues were revised several times as information on local practices became available. One might assume that the “pioneer” hromadas (communities) faced disadvantages as the “guinea pigs,” but this was mitigated by financial incentives: they received support from both the central budget and international organizations. By early 2020, there were 1,070 amalgamated communities in Ukraine, covering over 90% of the country’s territory. The remaining communities were mandatorily merged by the end of 2020. Today Ukraine has 1,469 communities, including 31 in the temporarily occupied areas.

Completion of decentralization reform: 2019-2024

In addition to merging communities, in 2020 the government reduced the number of rayons from 490 to 136, and the powers of rayon-level authorities were significantly cut. The distribution of funds between budgets was modified accordingly: money of liquidated rayons were allocated to communities.

At the end of 2019, a new Electoral Code was adopted, and in 2020, local elections were held according to the new rules. These rules specify quasi-open party list elections (quasi-open because voters cannot easily change the place of a candidate on a party list) for the councils of oblasts, rayons, and communities with more than 10 thousand people, a single-mandate system for councils of smaller communities, the election of mayors of cities with less than 75 thousand people by a simple majority, and of larger cities by an absolute majority (i.e., in larger cities there should be a runoff election if no candidate obtained over 50% of the vote in the first round).

This system is not perfect: it does not allow independent candidates to participate in elections (except for the smallest communities), and conditions for the movement of a candidate up the party list are rather restrictive. However, gender quotas introduced by the Electoral Code led to an increase in the share of women in local councils. Either because of the COVID pandemic or because decentralization allowed incumbent mayors to gain popularity by performing improvements in their cities, in 2020 local elections voter turnout was record low at 37%. Therefore, the incumbents easily won elections in the majority of cities (200 out of 363).

Another key decision made in 2021 was to allow communities to manage previously state-owned lands beyond their boundaries. This decision was made within the framework of land reform (opening of the land market — see Chapter 10) and should greatly increase the resource base of communities. Another law mandates that state and communal land only be sold via online auctions. This will make land sales more transparent and competitive.

Since the start of the full-scale war, hromadas where military units are located received disproportionately high personal income tax (PIT) revenues. Thus, in 2023, the government decided to transfer this “military PIT” to the state budget and use it for defense. While defense needs may justify some restrictions on local autonomy, unfortunately these funds were not used as intended. Therefore, at the end of 2024, Parliament allowed local councils to procure for military units.

In 2023, Parliament introduced competitive hiring for positions in local self-government and key performance indicators for public servants. It also reiterated transparency requirements for local council operations, which had already been common practice before 2022: publishing voting results, videos of discussions, protocols of commission meetings, etc. (these requirements will come into force after the martial law is lifted). In the mid-2024 Parliament provided more powers to local authorities in transborder cooperation (cooperation with municipalities and regions abroad). In 2024, communities were allowed to take out loans and at the same time medium-term budget planning for local budgets was restored.

Overall, decentralization reform increased public trust in local authorities, enhanced the conditions for social cohesion, and gave an impetus for transparency and open government. Moreover, the first local elections after the reforms allowed new people (among them more women) to enter local councils. Local politics became more meaningful as citizens gained more opportunities to participate in community decision-making. Local authorities also introduced innovative participatory tools such as citizens’ budgets.

An important element of local development and post-war reconstruction is the launch of the state urban planning cadastre. The cadastre will be used by local authorities, architects, and constructors. It will contain information from the register of damaged and destroyed property, the land cadastre, the geo-information system for regional development, the DREAM public investment project management system etc., as well as master plans, spatial development plans of communities, and other information necessary for construction.

What next?

Amidst the current war-related problems, local governments are busy with reconstruction (in communities that suffered from Russian attacks) and the accommodation of internally displaced people (in communities further from the frontlines). After the war, they will likely spend even more time on reconstruction, as well as assisting refugees who return to their communities. They can prepare for these challenges by adopting plans for community development, finding partners for reconstruction, etc.

The “Build Back Better” approach will require much more than simply rebuilding damaged houses and infrastructure. Cities and villages will need to become more inclusive, green, and energy efficient.

In 2025, the Ukrainian government should adopt the EU rules for the supervision of local self-government and transform local administrations (which are the regional representatives of the central government) into prefecture-type authorities. Ideally, these changes had to be introduced into the Constitution and thus complete the decentralization reform. However, under martial law, amendments to the Constitution are impossible, so Ukraine must adopt similar rules using “ordinary” laws. Some time ago, both Poroshenko and Zelenskyy introduced into Parliament draft laws on changes to the constitution to finalize the decentralization reform. However, these laws increased the powers of the president, undermining the powers of local authorities, and did not address a substantial problem of the current constitution — the overlapping powers of the president and the Cabinet of Ministers. Thus, when this draft law is introduced to Parliament, it should be carefully examined to ensure that decentralization reform is not undermined.

According to the Ukraine Facility, the distribution of powers between central and local governments should be clarified in 2026. The government will also study whether it would make sense to provide communities with legal entity status in line with the EU practice.

Besides legislative changes, proper implementation of decentralization reform will require significant effort from both the government and citizens. Although the war requires some centralization of power to ensure quick decision-making, this centralization should not turn into authoritarianism. All levels of the Ukrainian government must learn to share powers and responsibilities with each other and with citizens. This mechanism is even more vital under martial law, when elections are impossible. Thus, every citizen can find a way to participate in decision-making in their communities, for example, via civil society organizations or the “citizens’ budget” instrument that can be adapted to address the priorities of citizens during wartime (e.g., projects that support the local military, veterans, and their families).

Read the White Book of Reforms 2025 and previous White Books (2017, 2018, 2019) via this link.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations