High-quality public administration is one of the key prerequisites for progress in EU accession negotiations, as it determines how effectively and predictably the state operates. Ukraine has been reforming this area for a decade. We therefore set out to examine what has actually changed over this period, whether the reform has brought the country closer to its stated objectives, and if not, what continues to impede progress.

The article begins with an overview of the reform, while the results of the analysis of the key factors influencing it are presented at the end of the publication.

From 1991 to 2014, public administration in Ukraine retained many “Soviet” features, including excessive bureaucracy and opacity, as well as blurred or overlapping mandates among state institutions, which created ample opportunities for corruption and cronyism. In other words, the state system functioned in the interests of “its own”: the political and oligarchic elite rather than in the public interest. Attempts to reform this system began after the Revolution of Dignity.

Public administration reform is the restructuring of the public administration system to ensure the state apparatus is effective and professional. It includes revising the rules for entry into public service in state and local self-government bodies, improving incentives for high-quality performance, digitizing human resources management and the public services provided to Ukrainians, and redesigning processes to minimize opportunities for abuse.

Initially, political leadership and overall coordination of public administration reform rested with the Minister of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine; today, it rests with the Deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration of Ukraine.

A turning point came in 2015, with the adoption of a new Law on the Civil Service. It fundamentally changed the logic underpinning the formation of the state apparatus. First, the law enshrined the principle of political neutrality by separating political positions (ministers and their deputies) from the administrative positions of civil servants. The rationale was that while holders of political office change frequently, this should not entail replacing a significant share of ministry or agency staff. Civil servants are expected to ensure institutional continuity and the ongoing implementation of existing policies and programs; to this end, their work must be grounded in professionalism rather than political loyalty to a particular leader.

Second, the law introduced clear criteria and competitive recruitment procedures, requiring each officeholder to possess professional competencies aligned with the position. Third, it standardized procedures for evaluating civil servants, including annual performance assessments that directly affect the payment of performance-based bonuses.

For these changes to become a functioning system rather than a series of isolated initiatives, a clear roadmap was needed – an understanding of how and within what timeframes the new rules would be implemented. Accordingly, in June 2016, the government adopted the Public Administration Reform Strategy until 2021, together with a detailed implementation plan. The Strategy was primarily focused on building the civil service’s internal capacity to enhance the country’s competitiveness (Figure 1). At the time, the state set itself several key objectives: introducing effective public strategic planning; developing policies through specialized directorates; renewing personnel by expanding competitive recruitment and ensuring convenient public access to vacancies; and reorganizing the work of ministries to eliminate excessive bureaucracy, duplication, or functions that did not properly belong to them (such as the provision of administrative services, the management of state-owned assets, and inspection and oversight functions). In parallel, the government planned to expand access to public services both through Administrative Service Centers (ASCs) and online.

Figure 1. Comparison of indicators across key public administration reform documents

Over the five years of the Strategy’s implementation, not all measures were carried out (Figure 2). Despite this partial implementation, the first wave of reform laid the groundwork for subsequent changes:

- Strengthened the government’s capacity to plan and make decisions more systematically: first identifying strategic priorities and only then developing solutions to clearly defined problems, rather than acting on an ad hoc basis

- Modernized human resources processes by expanding the use of competitive recruitment for civil service positions

- Enhanced accountability through the publication of annual reports by central executive authorities

At the same time, several problems remained. In particular, competitive recruitment processes did not always attract candidates with the necessary skills, and the system for determining civil servants’ pay lacked transparency because uncapped allowances and bonuses were often used to increase compensation for loyal employees. The rollout of the Human Resource Management Information System (HRMIS) also progressed more slowly than anticipated: the system operated in test mode in only 19 central executive authorities, and by 2021 contained data on approximately 20,000 civil servants out of nearly 200,000, while training staff in legislative drafting and in approaches to performance evaluation required stable funding.

Figure 2. Percentage of measures and indicators implemented in each year of Ukraine’s Public Administration Reform Strategies

The new Public Administration Reform Strategy for 2022–2025 shifted the focus from developing the internal capacity of the civil service to strengthening its outward-facing dimension — services for citizens and businesses. The central objective became the creation of a service-oriented and digital state (Figure 1). Accordingly, the Strategy introduced new priorities: the digitization of services, greater transparency in the work of public authorities, and the resilience of state institutions. Earlier results made it possible to shift attention from laying foundations to improving the quality of what was already in place.

In 2024, the EU-adopted Ukraine Facility program, which directly links financial support to Ukraine’s implementation of reforms, identified public administration reform as one of its key focus areas. The indicators selected for the reform include:

- Reform of civil servants’ pay, including the division of remuneration into a fixed, or guaranteed, component (at least 70%) and a variable component (no more than 30%), as well as a reduction in the length-of-service allowance from 50% to 30% (implemented in 2025 by Law No. 4282-IX)

- Restoration of transparent recruitment based on professional competencies by the third quarter of 2026 (Draft Law No. 13478-1, which proposes reinstating competitive selection procedures, is currently awaiting consideration)

- Full digitization of the human resources management system by the first quarter of 2026, including the restoration of the Unified Civil Service Vacancy Portal (career.gov.ua) and the full launch of HRMIS

The ultimate goal of these changes is to build a professional civil service free from cronyism and corruption — one capable of implementing large-scale transformations in the context of Ukraine’s EU accession and of effectively managing the substantial investment volumes expected during reconstruction.

In parallel with the launch of the Ukraine Facility, in 2025 the government approved another key instrument — the Roadmap for Public Administration Reform. Unlike the Public Administration Reform Strategy, which is oriented toward the development of a digital state, the Roadmap sets out specific changes (Figure 1) that Ukraine must implement by 2030 in order to meet the requirements of future EU membership, with the aim of ensuring that public administration in Ukraine aligns with European standards of good governance.

The Roadmap is a document that sets out a list of priority reforms, implementation timelines, and responsible implementing bodies. It is based on recommendations of the European Commission presented in screening reports, reports on Ukraine’s progress under the European Union’s 2024 Enlargement Package, and the Ukraine Facility plan.

The Roadmap serves as the basis for the European Commission’s monitoring of a candidate country’s progress toward EU membership. Government approval of the Roadmap in the area of public administration reform is one of the mandatory conditions for opening negotiations under Cluster 1 “Fundamentals” of the EU accession process.

Public policy

At the outset of the reform, one of the most significant challenges was the lack of high-quality strategic planning and effective policy coordination. In 2018, SIGMA experts noted that policymaking in Ukraine was highly fragmented, with ministries operating in isolation and decisions made largely on an ad hoc basis, without adequate problem analysis, impact forecasting, or proper consultation. On average, across all parliamentary convocations, the Verkhovna Rada adopts only about 30% of government-initiated bills, whereas in EU countries this figure consistently exceeds 70%. However, this low rate was not the result of passivity on the part of the Ukrainian government but rather of an excessive number of draft laws submitted by MPs (several times higher than in most European states). At the same time, government-initiated bills in Ukraine tend to be of higher quality and are more likely to pass parliamentary procedures than MP-initiated bills, which aligns with European practice, where the executive branch is responsible for policy development, thereby ensuring a balance of power among institutions. Another problem identified in government reports was that up to half of the tasks assigned to the Cabinet of Ministers were completed with delays, indicating deficiencies in planning and monitoring implementation.

In response to these challenges, the government planned to update decision-making procedures by 2021, strengthen its analytical capacity, improve policy development mechanisms, including by involving stakeholders in decision-making, and optimize the structure of central executive authorities.

To strengthen the strategic and analytical capacity of the Cabinet of Ministers, a Department for Strategic Planning and Public Policy Coordination was first established within the Cabinet Secretariat. The Department was tasked with developing unified standards for drafting government acts, coordinating work across ministries, preparing medium-term government plans, and analyzing the implementation of reforms. Its first tangible outcome was the preparation of the Medium-Term Plan of Priority Government Actions through 2020, which consolidated previously fragmented priorities of individual ministries and the government into a single, coordinated framework. On this basis, annual plans for implementing priority reforms were developed, which were required to be realistic and achievable and to include clear evaluation criteria. It was at this stage that a link between reform planning and budget planning was introduced: when drafting the annual state budget, the government began to take into account the priorities set out in the Medium-Term Plan, meaning that funding was directed primarily to reforms included in government plans and accompanied by defined timelines and expected results. Although implementation of these plans has remained uneven — only about half of the planned measures were completed in 2023 — the positive development has been the emergence of a clearer understanding of the direction of travel and the pace of progress toward the goal.

Alongside the challenge related to reform planning, another issue remained — the quality of the policies being developed. Until 2017, analytical functions within ministries were performed primarily by policy development departments whose staff received standard civil service salaries, which limited the ability to attract qualified professionals from the labor market.

To strengthen the strategic planning capacity of government bodies, the government launched a pilot initiative to establish directorates (analytical units responsible for policy formulation and reform implementation) within ministries, as well as in the Cabinet Secretariat, the State Agency for E-Governance, the National Agency of Ukraine on Civil Service (NACS), and the Office of the President. These units were intended to support decision-making based on professional analysis and forecasting. At the initial stage, this model produced tangible results: supported by EU funding, the directorates attracted more qualified and motivated analysts (reform specialists) who received higher salaries and, as a result, improved the quality of decision preparation in a number of institutions. However, the sustainability of this model depended heavily on external funding. After EU support ended in 2020, ministries lacked sufficient internal resources to continue paying higher salaries, and beginning that year only a small share of directorate staff retained special status and higher pay, while most employees were transferred to the standard (significantly lower) civil service pay scales.

Under these conditions, the directorate model gradually lost its appeal. Beginning in 2021, the number of directorates started to decline (from 74 to 44 by 2023) and some ministries, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Economy, abandoned the model altogether. Additional contributing factors included the duplication of functions across other analytical units and the weak integration of directorates into ministries’ administrative structures. At the same time, the core problem remained the lack of stable funding and the absence of a clearly defined role for directorates within the decision-making system. Although the Concept for Optimizing Central Executive Authorities continues to treat directorates as a permanent structural element of ministries, without revising their functions, staffing models, and financial frameworks, this institution is unlikely to be sustainable over the long term.

Another step to improve policy quality was the creation (in 2016) of new standards for preparing strategic decisions and policy proposals. These standards require executive bodies, when developing policy, to analyze the problem, define objectives for state intervention, and consider possible solution options. For strategic documents (concepts, strategies, programs), a clear implementation plan with timelines, responsible parties, and a list of required resources is also mandatory. In 2018, these approaches were supplemented by a requirement to forecast the impact of government decisions targeting business on stakeholders.

These standards were legally enshrined in 2020 through the updated Rules of Procedure for the Cabinet of Ministers. Draft government acts cannot be submitted for consideration by the government without an analysis of the problem, a description of the expected results, and an assessment of the impact of decisions targeting business. Decisions must also be aligned with state strategies and be consistent with the budget. During policy development — that is, when introducing significant new rules or repealing existing ones through draft laws, resolutions, and orders — public consultations with stakeholders are required. In Ukraine, such consultations take place in two formats: broad consultations, when the government publishes a draft on its website and anyone may submit proposals, and targeted consultations with stakeholders, when the government itself invites relevant parties to participate in discussions. Last year, the requirement to conduct public consultations for executive authorities (the government and ministries) as well as for local self-government bodies was further enshrined in the Law on Public Consultations, although these provisions are suspended for the duration of martial law. By contrast, consultations are not mandatory for MP-initiated legislative proposals, lawmakers may initiate them voluntarily.

Although Ukrainian legislation requires impact analysis not for all government decisions but primarily for regulatory acts that directly affect business activity, the European Commission recommends assessing the impact of all government policies and decisions, rather than limiting analysis to business-related aspects alone. A similar situation exists with public consultations. SIGMA experts recommend establishing a mandatory requirement to consult the public on all regulations approved by the government, as consultations are currently mandatory only for acts affecting citizens’ vital interests or the legal status of civil society organizations, as well as specific aspects of their activities and financing. This gap is partially addressed by the already adopted Law on Public Consultations, which will enter into force after the end of the war — the remaining “gray area” is the non-mandatory nature of consultations for MP-initiated initiatives.

Civil service

Effective government is impossible without professional, motivated civil servants. They implement government decisions, ensure the functioning of institutions, and work with citizens on a daily basis. For this reason, one of the key questions of the reform is who enters the civil service and how. Clear rules for competitive recruitment are intended to increase the professionalism of the state apparatus and overcome societal biases against civil servants and civil service careers. Because anyone can participate in an open competition, this approach is meant to dispel the stereotype that the civil service is reserved only for insiders.

To this end, in 2015 the Verkhovna Rada adopted a new version of the Law on the Civil Service and introduced a competitive system for entry into the civil service. Candidates began to be selected by competition commissions established within the public authorities where they would ultimately work. For the highest-level positions, a separate Senior Civil Service Commission was created to ensure the independent and professional selection of senior managers; its membership included representatives of state authorities, civil society, and experts in public administration. Subsequently, the Cabinet of Ministers approved uniform rules for conducting competitions, including external oversight of competition commissions by the National Agency of Ukraine on Civil Service (NACS), mandatory publication of meeting protocols and results, and competency-based assessment of candidates through testing, practical assignments, and interviews. To improve access to information on vacancies, in 2018 the Unified Civil Service Vacancy Portal (career.gov.ua) was launched, allowing users to track open positions and announced competitions and to apply for them online.

The main wave of competitions took place between 2016 and 2018. In 2016 alone, public authorities announced more than 7,500 competitions to fill Category B and C positions. In the same year, the Senior Civil Service Commission conducted 109 competitions, resulting in the appointment of 38 Category A civil servants. Overall, between 2016 and 2018 the Commission conducted more than 200 competitions and appointed approximately 150 individuals to senior positions. As a result, more than half of the top positions in the state (according to data from the National Agency of Ukraine on Civil Service, there were 191 Category A positions in Ukraine in 2018) were filled through open procedures, representing an important step toward dismantling the long-standing practice of closed-door appointments.

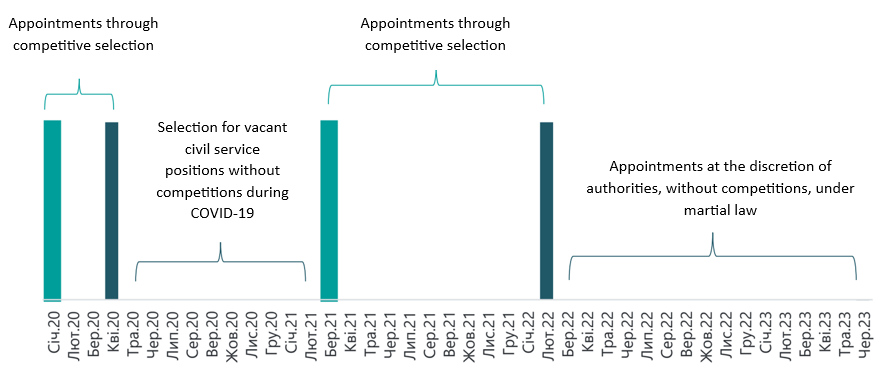

Figure 3. Appointments to vacant civil service positions, 2020-2023

However, the subsequent development of the reform proved far more complex than its initial results suggested. In 2019, the newly elected Parliament adopted the so-called “law on rebooting power“, which simplified procedures for appointing and dismissing civil servants. The law allowed senior civil servants to be dismissed without a clearly defined procedure and made it possible to fill these positions without holding competitions. This led to an increase in staff turnover (from 5% in 2018 to 12% in 2019) measured as the ratio of dismissals to the total number of civil servants. In addition to formal grounds such as disciplinary violations or a negative performance evaluation, Category A civil servants could now be dismissed without objective justification, based on a submission by the prime minister, a minister, or the head of a state body. In such cases, the civil servant must be offered a vacant position no lower than Category B; however, if no such vacancy exists or the civil servant declines the offer, dismissal follows. As a result, civil servants became dependent on political will — they could be dismissed for disloyalty rather than job performance. While this enabled political leaders to rapidly assemble their own teams, it simultaneously exacerbated high turnover in the civil service and created risks of declining professionalism and the loss of institutional memory.

In 2020, competitions were suspended in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and to allow critical vacancies to be filled quickly under crisis conditions without lengthy procedures. They were reinstated only seven months later. Between April and September 2020, selection without competitions was carried out for 79 Category A civil service positions — almost one-third of all top civil servants in Ukraine (according to data from the National Agency of Ukraine on Civil Service, there were 241 Category A positions in Ukraine in 2020). In May 2022, for security reasons related to Russia’s invasion, competitions were again temporarily suspended. As a result, for the third consecutive year candidates for civil service positions have been selected through direct appointments. This creates a risk of recruiting personnel who may be loyal but lack the necessary competence into the civil service. In July 2025, Draft Law No. 13478-1 was registered in the Verkhovna Rada, proposing the restoration of competitions for civil service positions; the bill is currently under consideration.

Due to the war, the Unified Civil Service Vacancy Portal was also suspended. The main reasons for shutting down the portal were the need to protect citizens’ personal data and to prevent cyberattacks on the system. The portal has not yet been restored. This complicates efforts by public authorities to recruit specialists for vacant positions and makes it more difficult for job seekers to search for and compare civil service vacancies. The Ukraine Facility plan requires the portal to be restored by the end of the first quarter of 2026. The government attempted to partially offset the absence of the portal through an experimental project by publishing vacancy information for only two ministries (the Ministry of Digital Transformation and the Ministry of Economy) as well as the National Agency of Ukraine on Civil Service and the state-owned enterprise Diia, on the Diia web portal. However, this cannot be considered a full replacement for the portal, as the Unified Portal allowed applicants to submit documents and review competition results, whereas Diia lacks such built-in functionality. Moreover, Diia provides information only on a subset of vacancies in selected ministries, meaning that candidates may simply be unaware of some open positions.

Another important area of reform is the implementation of HRMIS — the Human Resource Management Information System. It was launched as a pilot project in 2019 and introduced in the Ministry of Finance, the Cabinet of Ministers Secretariat, and two state agencies: the National Agency of Ukraine on Civil Service (NACS) and the State Agency for E-Governance. The system was fully rolled out in 2021. By 2022, 67% of state bodies had implemented HRMIS, and as of May 2025 this figure had reached 87%, exceeding the annual target of 80%.

The system enables the maintenance of a digital registry of civil servants, automates the posting of vacancies and the conduct of competitions, stores the results of performance appraisals and professional development, and generates analytics for workforce planning. The implementation of HRMIS has not yet been fully completed, in particular because some institutions lack the necessary equipment and system support specialists, while staff also lack the skills required to work with the system.

A second major weakness of the civil service is an uneven and outdated compensation system. Even when competitive recruitment functioned fully, the state often lost out in competition for skilled professionals due to uncompetitive pay and significant disparities in base salaries for comparable positions across different agencies. A portion of remuneration was formed through length-of-service allowances, rank-based supplements, and bonuses, which largely depended on managerial discretion. As a result, employees with longer tenure systematically received higher incomes, while young and highly qualified professionals faced uncompetitive conditions (even after successfully passing open competitions). According to NACS estimates, in 2019-2021 only 21-22% of civil servants were satisfied with their level of pay. Rebalancing the compensation system (by reducing the role of tenure and subjective factors and strengthening the link between remuneration and competencies) was therefore necessary to attract and retain young professionals at the start of their careers in the public sector.

Positive shifts in this area have become evident over the past three years. In March 2025, Parliament adopted a law introducing a more transparent approach to compensation. Salaries will consist of a fixed component (base salary, length-of-service supplement, and rank supplement) and a variable component — bonuses. The total amount of bonuses in a given year may not exceed 30% of the fixed component of pay. In 2023, the government introduced a job classification system for calculating compensation and approved a salary scale that takes into account job families and levels, jurisdiction, and types of state bodies.

Civil service positions are classified according to the following criteria: job family, job level, jurisdiction, and type of state body.

- Job family — a group of civil service positions united by shared core functions and areas of work. In total, 27 job families are defined. For example: 1 – administrative leadership; 11 – corruption prevention; 24 – human resource management. A position is assigned to a job family based on the area of activity that occupies most of the working time;

- Job level — within each job family, several levels reflect the complexity, responsibility, and place of a position within the organizational structure of a state body. In total, there are nine levels: I (first) through VI (sixth) managerial levels, and VII (highest) through IX (entry-level) professional levels;

- Jurisdiction — the territory over which a state body’s authority and activities extend. Jurisdiction is classified on a scale from 1 to 3: 1 – entire territory of Ukraine; 2 – regions, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, as well as territorial offices of central bodies covering one or several districts or cities of regional significance; 3 – one or several districts, districts within cities, or cities of regional significance;

- Type of state body — within each jurisdiction, state bodies are divided into three types: 1 – key bodies ensuring the functioning of state power (the Verkhovna Rada, the Cabinet of Ministers); 2 – ministries and central executive authorities that formulate policy in specific areas (for example, the National Securities and Stock Market Commission, the State Judicial Administration of Ukraine); 3 – other state bodies and their territorial subdivisions.

Another factor that makes the civil service unattractive is excessive financial scrutiny, which continues even after an individual leaves office. In Ukraine, there is a practice of enhanced financial monitoring of politically exposed persons (PEPs) — that is, individuals who have held senior public positions (presidents, prime ministers, ministers, members of Parliament, senior judicial officials, and others) — as well as their close relatives. The rationale for this approach is the perceived risk that such individuals may retain influence even after leaving office. As a result, banks are required to subject PEPs’ financial transactions to heightened scrutiny and may block their accounts or refuse to provide services, while the individuals themselves must continually explain the origin of their funds. In 2023, Ukraine introduced lifetime PEP status, abolishing the three-year post-employment period. In effect, anyone who has once held a senior public position is subject to enhanced (and often excessive) financial monitoring for life.

A similar problem exists in the area of electronic asset declarations. In most countries, financial disclosure requirements focus primarily on senior officials, and the state determines who should be monitored and with what level of intensity. In Ukraine, electronic declarations apply to all civil servants, regardless of their level of influence or corruption risk. As a result, the absence of a risk-based approach (both in verifying declarations and in defining the duration of PEP status) means that oversight becomes broad and formal rather than targeted and effective. For potential candidates, this represents a disproportionate personal and financial burden, making civil service positions less attractive than employment in the private sector.

Accountability and transparency

Accountability means that state bodies are required to openly explain their decisions, respond to criticism, and take responsibility when they break the law or fail to fulfill their duties. In public administration, accountability is usually divided into two dimensions: internal accountability (audits, performance monitoring, and internal procedures) and external accountability (oversight by civil society, Parliament, the media, open data, and public consultations). Both dimensions are essential for reducing corruption risks, strengthening trust in government, and improving the effectiveness of public policy.

Internal accountability involves a state body assessing its own activities. Its purpose is to identify violations, evaluate the effectiveness of programs, and prevent the misuse of funds. For example, all state bodies and budgetary institutions are required to have an internal audit unit. Such units conduct both planned audits (once a year) and ad hoc audits at the request of management or in response to complaints, suspected abuses, or the improper use of resources.

A separate element of internal accountability is the comprehensive performance audit of state budget spending, which has been conducted by the Accounting Chamber of Ukraine since 2020.

External accountability refers to the ability of public bodies to report openly to citizens and other institutions. Since 2016, the government has systematically expanded openness tools, including open budgets, the Prozorro e-procurement system, and the unified open data portal data.gov.ua, which currently contains more than 39,000 datasets from central and local authorities.

Since 2012, Ukraine has participated in the global Open Government Partnership initiative. Every two to three years, the government adopts an Action Plan aimed at increasing transparency, accountability, and citizen engagement. In 2023, the government launched the sixth Open Government Partnership action plan, which includes 10 commitments. These include introducing a digital tool for managing the reconstruction of infrastructure, construction, and real estate projects (DREAM); monitoring the development of regions and communities; and ensuring access to public information in the form of open data, among others. In December 2025, the government plans to approve and present the seventh Open Government Partnership action plan, which will cover 2026 and 2027.

The introduction of e-petitions in 2015, along with public consultations and open databases, has also enabled citizens to directly influence policy-making. The Law on Public Consultations, adopted in 2024, introduced unified rules for dialogue between the authorities and society during the preparation of policy documents and regulatory acts. It provides for online and offline consultations and requires the publication of their results, bringing Ukraine’s system of governance closer to EU open government standards.

Thanks to these initiatives, Ukraine ranked among the world’s top five countries for open data maturity in the European Commission’s Open Data Maturity Report 2024. In the report, Ukraine’s open data maturity is assessed at 97%, compared with an average of around 80% for EU countries.

At the same time, SIGMA’s 2023 assessment shows that accountability mechanisms do not yet fully permeate the day-to-day activities of public bodies. In many authorities, internal audit still plays a consultative rather than a control role. At the same time, pressure from the EU integration process (through regular European Commission monitoring of the reform roadmap) is gradually creating demand for substantive rather than purely formal accountability.

Service delivery

Before the reform began, the system for delivering administrative services was marked by fragmented responsibilities: to obtain a service, citizens often had to visit multiple offices and collect paper documents from different institutions. This created opportunities for corruption, as outcomes depended heavily on individual officials and there were no unified service delivery standards. In 2013, around 32% of citizens considered the quality of administrative services in Ukraine to be poor, while only 12% rated it as high.

This created a need to move away from the Soviet-era logic of a “state as controller”, which forces people to move from office to office and prove their entitlement to services, toward a service-oriented state model in which services are delivered in a client-focused and timely manner.

The main driver of the modernization of service delivery was the rollout of a nationwide network of ASCs operating on a one-stop-shop principle, followed by a broader shift toward comprehensive digitalization.

The first centers where citizens could receive a significant share of services under the one-stop-shop principle began to be rolled out in 2013. Key innovations included the introduction of electronic queues, uniform rules for accessing services, and a clear service model in which an administrator supports applicants and helps them navigate all stages of the process.

However, the expansion of the ASC network in 2013-2014 was relatively slow, as local self-government bodies had limited resources and authority to establish fully functioning centers. As a result, such centers were located mainly in large cities. The active phase of expansion began after the launch of decentralization in 2015, when local communities gained financial autonomy and broader powers to develop their own service delivery infrastructure.

By 2018, 767 ASCs were operating in Ukraine, collectively delivering around 20 million administrative services — from the issuance of passports to business registration. By the end of 2022, such centers were operating in all district centers across the country and were actively expanding in local communities. Today, around 5,000 ASCs operate in Ukraine, and as of the end of November 2024, satisfaction with the quality of services provided stood at 94.7%. Alongside the expansion of the center network, the government has been upgrading existing facilities and opening Diia.Centers — modernized ASCs where, in addition to administrative services, citizens can receive business consultations, learn how to use online services independently, obtain free legal assistance, and access computers with internet connectivity. Currently, 86 such centers are in operation. At the same time, accessibility remains a challenge: as of the second quarter of 2025, the level of barrier-free access in ASCs stood at 72%. The situation is particularly difficult in de-occupied and war-affected communities, where damage to or destruction of buildings requires services to be provided in temporary premises that often fail to meet inclusivity standards.

To address this problem, a mobile service delivery mechanism was introduced through mobile service units and portable service kits (“digital suitcases”). These tools allow ASC staff to travel in response to citizens’ requests. Mobile units provide access to basic administrative services (such as document processing, access to social services, benefits, and certificates), particularly for residents of remote areas, people with limited mobility, and internally displaced persons. As of today, 32 mobile service units and 406 digital suitcases are in operation in Ukraine. In the second quarter of 2025, 7,500 people used these mobile services (primarily residents of border and frontline areas).

Another important step was reducing dependence on the human factor in service delivery. In the traditional “paper-based” model, the quality and speed of services depend heavily on the individual employee: their experience, attention to detail, or even personal attitude toward the job. Digitizing the public service delivery system therefore became a logical continuation of the reform. Today, 871 ASCs use information systems in their day-to-day work, including the Vulyk system, which allows service delivery processes to be automated. An administrator only needs to enter basic data, after which the system generates the decision, prepares the required document package, and checks compliance with applicable requirements. This minimizes the risk of errors and makes it possible to deliver services more quickly.

In parallel, government services have been increasingly digitized, simplifying access by moving services online and reducing the need for physical interaction with officials. In Ukraine, digital services are primarily delivered through Diia. Through the Diia web portal and mobile app, more than 130 services are available, including electronic passports, digital driver’s licenses, and one of the world’s fastest business registrations for sole proprietors (FOPs). In 2024, Ukraine ranked among global leaders in the digitalization of public services, placing fifth in the UN Online Services Index. According to the UN E-Participation Index, which measures citizen engagement in public processes through online platforms, Ukraine ranked first worldwide.

According to survey data, 52% of the population say that receiving services online is the most convenient and effective option. Most users access online services through Diia (42%). As a rule, younger people dominate among online service users: while 73% of respondents aged 18-29 have used at least one online service, this figure drops to just 22% among those aged 70 and older. This is why it is important that, alongside large-scale digitalization, the state continues to develop alternative service delivery channels (such as ASCs) which provide access to services for people with low digital skills.

What’s next for the reform?

The European Commission’s latest report confirms substantial progress in governance: Ukraine has met a significant share of the requirements, which in theory would be sufficient to open the negotiation clusters. However, political blocking by Hungary continues to delay a formal decision. In this situation, it is important to continue reforms without interruption so that, once the political obstacles are removed, Ukraine can move quickly to open and close negotiation clusters in parallel as part of the EU accession process.

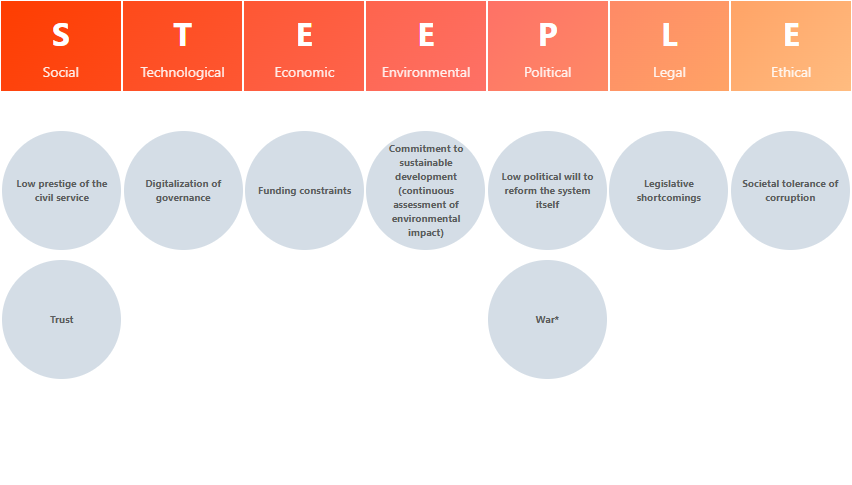

Still, the pace of public administration reform will depend not only on political decisions. A STEEPLE analysis, followed by the application of the foresight method Future Wheels, showed that the speed and trajectory of the reform are shaped by a wide range of factors: from the prestige of the civil service and staffing shortages to the stability of funding, political will, and public trust (Figure 3). These factors can either accelerate the reform or significantly slow it down.

Foresight methods are tools for the systematic analysis of the future that make it possible to identify trends and anticipate their impact on social relations. Unlike traditional forecasting, foresight does not seek to predict a single, exact future; instead, it develops a range of alternative scenarios. The Future Wheels foresight method makes it possible to identify not only direct but also indirect pathways through which different factors exert influence.

Figure 4. Drivers of change in public administration reform in Ukraine (interactive chart available via link)

Note: *War is a cross-cutting factor that affects several areas; however, in this analysis it is treated as a political factor.

Over the past decade, Ukraine has moved from fragmented initiatives to a systemic public administration reform: open competitions for all positions, including senior ones; open data; transparent procurement; the digitization of services; and accountability becoming a real principle rather than a declaration.

However, the reform is still unfinished. The most difficult part is changing the management culture, shifting from the formal observance of rules to genuine responsibility for policy development, and from “paper-based” accountability to substantive accountability. It is this stage that will determine how quickly Ukraine advances on its path to EU membership.

We thank experts from the NGO Professional Government Association (PGA), the Center for Political and Legal Reforms, the NGO Center for Democracy and the Rule of Law, and the Ukrainian Political Science Association for their external review of the material.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua/

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations